Back to selection

Back to selection

At 30, Miami Film Festival Finds its Niche

The Miami International Film Festival wrapped its 30th edition this past weekend, unspooling 138 films across 10 days. The program was strong enough across its myriad sections that many longtime observers were calling it the best iteration of the festival in memory, with a smattering of noteworthy films pulled from the mega festivals sprinkled across a wide reaching selection of work new and old. While light on significant premieres, sandwiched as it is between True/False and SXSW, it is a well-oiled machine, organized and efficient, with well-attended screenings that start on time in multiplexes, microcinemas and beautiful movie palaces such as Miami’s The Olympia, a 1920s tropical-themed theater that was the first building in the South to have air conditioning. It is a festival that most big cities should long for. There is never a dull moment and plenty of Miami Beach parties.

In the past, the event has struggled to cultivate an identity for itself, but under current festival director Jaie Laplante, an easygoing character with incredibly catholic tastes, it has become a destination of Spanish-language cinema from the Americas, with its Knight Foundation sponsored Ibero-American Doc and Narrative competitions being the centerpiece of an increasingly sprawling event. The From the Vault section housed a series of fun retrospective screenings, such as Leon Ichaso and Orlando Jimenez-Leal’s seminal Miami- and New York-set indie El Super, a Brady Corbet-hosted screening of Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar and a 20th anniversary screening of Frederick Wiseman’s Zoo (a look at the Miami Zoo), while the Visions program held such international fest circuit heavyweights as Carlos Reygadas’ Cannes-winning Post Tenenbras Lux and Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel’s already legendary Leviathan.

The festival found a place for the best movie this critic has ever seen about the life an times of a writer, Hannah Arendt, German titan Margarethe Von Trotta’s magnificent meditation on the German-Jewish political theorist. Starring Barbara Sukowa as the title character, who lived a life few if any can match, it is major work, spartan, highly dramatic, and incredibly timely. It focuses on the period immediately before, during and after Arendt’s famous coverage of the Adolf Eichmann trial in Jerusalem for The New Yorker, in which she coined the term the “banality of evil” (she saw Eichmann as a mediocre bureaucrat simply following orders, “terrifyingly normal”, not one of history’s great monsters and maybe not even an anti-Semite) and suggested that collaboration on the part of key members of the European Jewish leadership allowed the death toll to rise.

In the wake of this, she received death threats, was physically harassed by the Israeli government, asked to resign by The New School, where she taught, and ridiculed by the Norman Podheretz crowd at Commentary (“violates everything we know about the Nature of Man,” he wrote) . She was also promptly ostracized by many in her own community, including her longtime friends Hans Jonas and Kurt Blumenfeld, the latter with whom she had escaped capture by the Nazis, the former her friend and fellow Heidigger pupil, who turned on her just as he had their teacher because of the apolitical man’s half-hearted Nazism (she however, had been Heidigger’s lover and sought to understand him where others had cast him to damnation). Impeccably crafted on every conceivable level, as committed to the world of ideas and unwilling to yield to ignorance and blood lust as its title character, it is an important film, one which rejects the simplistic visions of a complex, morally dubious world that so many would foist upon us. It shows how quickly a search for justice and closure can turn into hysteria and an insatiable desire for revenge. What you see in this film is the beginning of the terrifying world we live in today, one in which vengeance and tribalism are as important factors on the world stage as ever before.

Among the gala screenings was an absolutely absurd, avant-retard classic in the making, and a world premiere to boot. Writer-director Jokes’ (I’m not making that up) feature Eenie Meenie Miney Moe is heavy on style and light on substance (goes without saying), but this might be the single most over-the-top, stereotype-laden, obscene-for-its-own-sake, misogynistic-without-seeming-to-try Miami Latin gangster picture of all time. Focused on a tow-truck driver, played by Andres Dominguez, who jacks people’s cars (generally drug dealers), rips them off and sells the cars to chop shops, he of course dreams of the straight life, has an impossibly hot series of women who are happy to yell at him for his two-bit hood lifestyle or have sex with him on some of the town’s beautiful beaches.

He eventually gets in trouble with some Russian mobsters, one of whom was his friend until a drug deal gone wrong. Almost every scene begins with yelling of one sort or another and I doubt there is any aspect of the production that isn’t derived from some far better, although likely still mediocre, gangster picture of yesteryear. People say things like, “Do you know what I love about Miami? Everybody is dirty. And to get money, you have to get dirty too!” The ending involves half the cast uncomprehendingly taking bad ecstasy and dropping dead. Although the club scenes and car chases are shot with some competence if willful and self-limiting indulgence, the same cannot be said for the acting, writing or anything involving a day interior. What’s not to like?

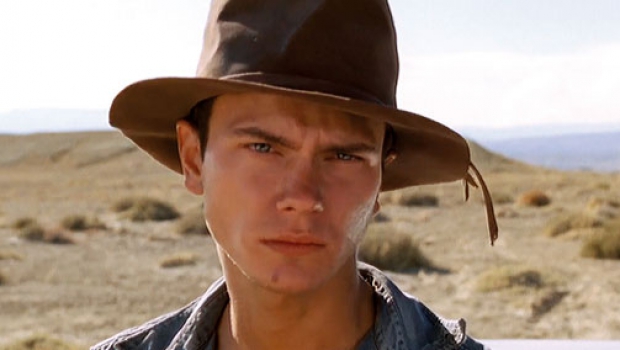

Dutch octegenarian director George Sluizer, who is most famous stateside for his Oscar-nominated The Vanishing, its entertaining if not nearly as terrifying American remake, and his accusation that he once saw Ariel Sharon shoot unarmed Palestinian refugee kids for fun (a story he recounted to this author first hand), was in Miami to present the North American premiere of Dark Blood, which will forever be known as the film River Phoenix was making when he dropped dead outside an L.A. nightclub. Sluizer, who is now terminally ill, claims that he was 72% done with the film when Phoenix passed. After receiving notice that his own days were limited five years ago, he set out to make the movie presentable, offering a metaphor in voiceover during the film’s first shot, a set still of him and Phoenix, of wanting to give a chair with two legs a third so it might stand on its own. It doesn’t, at least not in the way that, say, Polish wild man Andrzej Zulawski’s On The Silver Globe does, another film that was shut down midshoot and subsequently saved by the director, who reads descriptions of scenes where the lost or never shot footage would have been.

Still it is a fascinating last look at Phoenix, who is magnificent as a lonely Western mystic, possibly dangerous, who is encountered by a pair of married Hollywood actors (Jonathan Pryce and Judy Davis — how I miss her, where has she gone!?) whose Bentley breaks down in the middle of a rarely traversed desert expanse. Some Straw Dogs-esque sexual brinksmanship ensues after he promises to go out and fix the couple’s car, but he keeps them waiting for a guest to arrive or for his own truck to be fixed. Soon it becomes quite clear he has other intentions for them entirely as things get weird fast, the specter of Phoenix’s long-dead Navajo wife, felled by cancer after being exposed to radiation from U.S. nuclear testing, looming over the proceedings. It becomes quite clear this episode will not end well, but the movie has several leaps in plausibility that may have been smoothed out in the missing scenes. Regardless, Phoenix was impressive until the very end, Davis is spectacular as always and Ed Lachman’s lensing is beautiful and true. Here’s hoping, despite its various missteps, it finds its way to availability, as it took quite a bit of courage given the tragedy surrounding it to finally bring it to light.