Back to selection

Back to selection

Time Frames

Cracking the archives of early cinema. by Nicholas Rombes

The Invention of Paramount Pictures

The Media History Digital Library is a goldmine of information about early cinema, the sorts of magazines, journals, and trade publications that, in the pre-digital era, had only been available to those able to travel to research libraries. At over 800,000 scanned pages and growing, the collection is daunting, and what I plan to do in Time Frames, a five-part series, is cull through and select a series of images and text from the collection to highlight key transformative moments in the film culture and industry, as well as other oddities and obscure artifacts.

It’s perhaps impossible for us not to impose a sense of foregoness to history; since we know the outcome, we see it coming in the sources. And when writing about the past, we can’t help but impose our knowledge of what happened. We know, for instance, that the nickelodeon gradually gave way to the movie house, and that the small, local film production companies of the 1910’s merged or disappeared as Hollywood emerged. Yet that path was not straight, and our hindsight knowledge of what happened, of how things played out, tends to obscure or gloss over the rough spots, the detours, the eruptions, the digressions, the upstarts of randomness and chaos that are always part of the fabric of history.

So, rather than a linear “history of” column, Time Frames will be more akin to linked snapshots, focusing less on the overall historical narrative at hand, and more on the texture of the images, the voice of the text, once obscured in archives but now made available to us, in all their raw, real-time glory.

This first installment explores some early promotional material from Paramount Pictures, dating back to 1914, when Adolph Zukor’s The Famous Players Film Company and The Lasky Feature Play Company released their films through Paramount, which had been founded by William Wadsworth Hodkinson earlier that year.

Hodkinson hoped to move the fragmented film industry away from the decentralized nickelodeon experience to a national production and distribution model that would give producers more power and profits through strategies such as block-booking, which forced exhibitors to buy multiple films packaged together from the numerous companies that had exclusive agreements with Paramount. We see this in early promotional material (from Moving Picture World, an early trade paper) for the company from January 1915. (Note: click on images to enlarge and see the full view.)

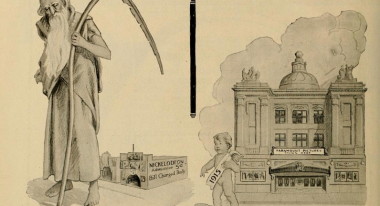

The old, small, decrepit nickelodeon on the left gives way to the newborn future: a palatial Paramount Pictures bidding farewell to “Cheap Houses, Destructive Competition, and Chaotic Conditions.” (It’s interesting that in 1915 competition could be called “destructive;” in 1948 the Supreme Court would issue an anti-trust ruling that would break up the oligarchy that was Paramount and other studios.)

The ad wishes away (as the old year) the chaos of the nickelodeon as well as its “daily change” (the fact that what was shown often changed from day to day) during the same era that continuity editing emerged as the basic grammar of what was to become the “classical” Hollywood style of narrative. It’s maybe worth considering how the emergence of continuity editing as the standard mode of visual storytelling through editing (pioneered by D. W. Griffith and others) was not simply borne out of a desire to find the most efficient ways to tell a story, but was rather part of a larger cultural drift and business model that, in the interests of consolidation and profit, labeled as “chaos” methods that were not smooth, uniform, and standardized. A promotional page from a few months later (March 1915) also from Moving Picture World stresses efficiency and regularization. Although a future column will explore links between Fordism (described by Steven Tolliday and Jonathan Zeitlin as “a model of economic expansion and technological progress based on mass production: the manufacture of standardized products in huge volumes”) and the emerging movie industry, it’s interesting how these early, inter-industry Paramount advertisements prepared the groundwork for the studio system business model.

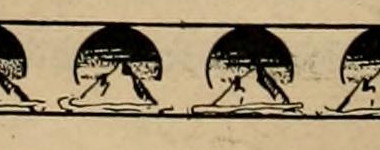

The ad also features an early Paramount logo, the first iteration of the mountain peak design (reportedly created as a doodle by Hodkinson himself), a logo that by 1917 would be modified to include billowing clouds at the base of the mountain rather than mist. In this and a few other illustrations from 1915, the finished logo appears in a film-strip like format, emerging out of sketches.

It’s a small detail, this filmstrip/border design, a sort of rough draft of Paramount working out, in public, its identity and image as a major distributor and, eventually, studio.

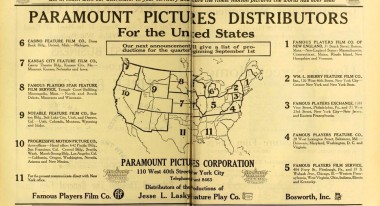

One of the more fascinating Paramount advertisements from its formative years is this map (from the July 1914 issue of Moving Picture World) of the United States segmented into distributor “territories.”

The ad features the very first, pre-mountain logo: a royal crown bearing the Latin phrase for “in the highest.” The totalizing scope and vision of the company — in which no corner of the U.S. is not claimed — suggests the grand designs of the company, as if there was no space beyond Paramount’s reach.

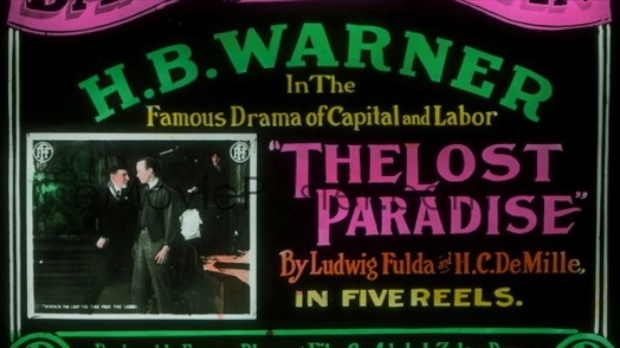

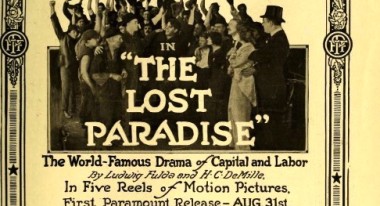

There is also an advertisement for the first film released by Paramount, The Lost Paradise, by Henry Churchill de Mille, Cecil B. de Mille’s father, adapted from the German drama by Ludwig Fulda.

An August 1891 New York Times review of the de Mille’s American stage version (upon which the Paramount Pictures film, released in the late summer of 1914, was based) describes it as a drama about “the war of classes against masses.” The drama contains this exchange, between Standish, whose family owns an iron works factory, and Hyatt and Schwartz, workers threatening to go on strike:

HYATT: Capital can’t do without labor.

STANDISH: What can labor do without capital?

SCHWARTZ: Which comes to any country first? What built your factories and your railroads, and your fine houses? Your sleepless nights didn’t. ‘Twas this–and this. (slapping first the muscle of one arm, then the other, extending both) Your brains are used to make machines of us. We’re tryin’ hard to be patient and fight you brain to brain.

STANDISH: For what?

SCHWARTZ: Some of the benefits from the capital, that our own labor has made.

Although contemporary reviews of the film are difficult to find, an article in the October 1914 Lake Shore News (out of Wilmette, Illinois) notes that “The Lost Paradise is a powerful pictorial argument in behalf of the oppressed laborers, whose lives build the wealth of nations, whose tears are crystallized in the jewels of the rich.” So it turns out that the very first release by the motion picture company that would become a symbol of unfair trade practices was one that dealt in complex and sympathetic ways with the plight of workers. It’s also a sign of the times that Edwin S. Porter — a pioneer of early cinema whose films The Great Train Robbery and Life of an American Fireman (both 1903) had experimented with cross-cutting and other then experimental editing techniques — is listed near the bottom of the advertisement as a “technical director.” In these and other early promotions, the film’s director was often not listed, as distinctions between cameraman, writer, director, and editor were often blurred, overlapping, and collaborative. The concept of the director as author of a film, responsible for its total vision, had not yet fully emerged.

Porter is an interesting example. Having failed to establish consistency and uniformity of method — which was precisely the business and artistic model that Paramount was striving for — Porter’s star faded.

By 1916 he had abandoned filmmaking.

Next installment: Film “vamps” in the teens.