Back to selection

Back to selection

Time Frames

Cracking the archives of early cinema. by Nicholas Rombes

Meta-Vamping

This second installment of Time Frames draws on The Media History Digital Library, a reservoir of information about early cinema that includes the sorts of magazines, journals, and trade publications that, in the pre-digital era, had only been available to those able to travel to research libraries. At over 800,000 scanned pages and growing, the collection is daunting. In Time Frames I’ll cull through and select a series of images and text from the collection to highlight key transformative moments in the film culture and industry, as well as other oddities and obscure artifacts.

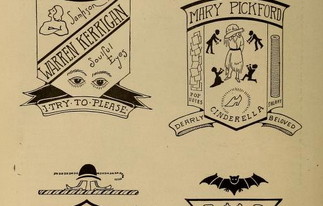

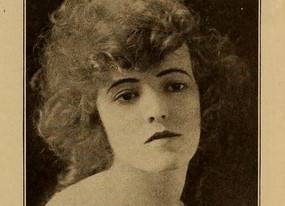

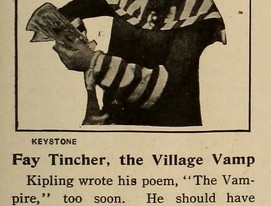

In the pre-Code, chaotic world of cinema from the teens, the “vamp” emerged as one half of a remarkable feminine duality that–on the “innocent” side–included Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish. The term itself derived from a poem by Rudyard Kipling that, in 1897, appeared as the museum catalog text to accompany The Vampire, a painting by Philip Burne-Jones.

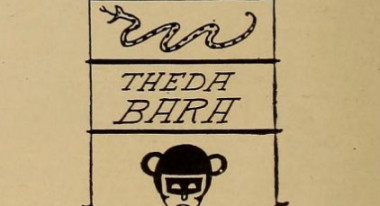

In 1915, Theda Bara appeared in the film A Fool There Was, adapted from a 1909 Broadway play whose title was taken from the Kipling poem. The story–which centers on a married diplomat who falls under Bara’s sexual spell to ruinous end–and Bara’s unrestrained, sexually aggressive performance, helped usher in the era of the vamp, which roughly corresponded with the women’s suffrage movement in the United States.

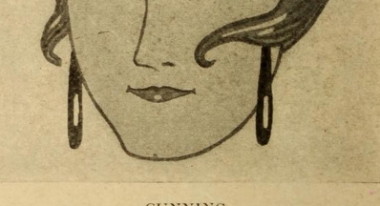

Coded as both powerful and evil, the vamp was–like the femme fatale in the 1940s, a figure of complexity and contradiction. In some ways, she was a progressive archetype, an intelligent, resourceful woman whose seduction of men exposed their hypocrisy and weakness, and whose magnetic presence on the screen had the potential to cause audiences to identify (if not sympathize) with her actions. And yet the vamp was also the product of deeply conservative impulses that relegated women to the status of temptress and sexual object. In “Vampire Popularity–Why?” from a November 1916 essay in Moving Picture World, it’s suggested that the vamp appeal to female audiences is based on “a combination of the attraction of fine clothes and a desire to see some film heroine get even with the male sex.” And:

The woman who trembles when her husband fusses over the overdoneness of the morning’s poached eggs just loves to fancy herself making cringing, creeping slaves of about five men at once. . . . The woman who has always been conventional takes an unholy delight in watching the dame of the screen perk up and get wicked enough to smoke a real cigarette.

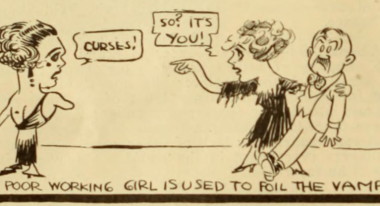

An early form of spectator theory, before it was called that and became the subject of film theory, pre-Hollywood articles such as this explored not only the manufacture and publicity of vamps and other character types, but also their complex appeals and relationship to spectators. In the context of the suffrage movement, the vamp’s dangerous ways (the word “homewrecking” is used in more than a few vamp-related articles) seem to be contained and made safe through humor, as in the General Liggett/Theda Bara caption, below, that, with a wink, assures readers that “Mrs. Liggett was there all the time.”

Rather than exploring specific vamp films, this installment of Time Frames looks at the rich and varied ways in which the vamp–and “vamping”–were portrayed in silent-era film magazines and journals. I’ve tried to dig deep into the journals to find images and text that haven’t been widely seen before. Although scholars such as Robert B. Ray (especially in his essential book A Certain Tendency of the Hollywood Cinema) and others have explored the growing sense of self-reflexivity and “meta” in audiences and in Hollywood movies during the 1950s and 60s as television began to erode and deconstruct Hollywood formulas, one of the surprising things I found was how relentlessly self-aware the emerging film industry was in the teens. The process of production–whether the production of stars like Lillian Gish, or the production of the films themselves and their reliance on genre conventions–was treated with a sort of self-deprecating knowingness.

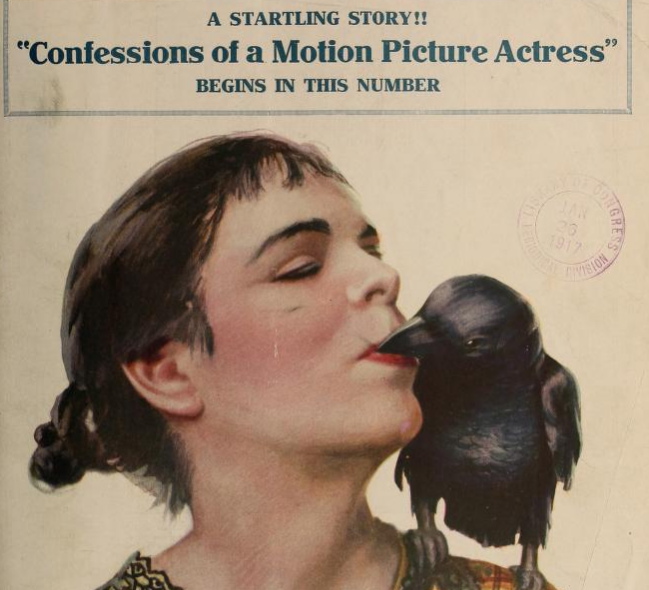

In her essay “Spring Styles in Vamping” from the June 1917 issue of Film Fun, Esther Linder interviewed four “vampire ladies of the screen,” including Theda Bara who told her:

I am always wondering about myself, and consequently I have always something to think about, and I am happy. To prevent the contingency of my ever understanding myself, I have hired an excellent corps of publicity writers. They turn out new stories about me every day.

That tone of detached amusement is a curious one that threads through much of the vamp-related writing, almost as if the players and the production companies were reaching a new awareness of their power. And yet there was still a playful, self-mocking spirit to their words in this era before stars became ruthlessly managed. I’ve tried to capture a sense of that freedom and humor–and the “meta”-ness of it all–in this selection of images. Click on each on to view it full-sized.