Back to selection

Back to selection

Time Frames

Cracking the archives of early cinema. by Nicholas Rombes

The Censors: Short-Haired Women and Long-Haired Men (and a Note on Hegemony)

This third installment of Time Frames draws on The Media History Digital Library, a reservoir of information about early cinema that includes the sorts of magazines, journals, and trade publications that, in the pre-digital era, had only been available to those able to travel to research libraries. At over 800,000 scanned pages and growing, the collection is daunting. In Time Frames I’ll cull through and select a series of images and text from the collection to highlight key transformative moments in the film culture and industry, as well as other oddities and obscure artifacts.

Note: click on images to enlarge.

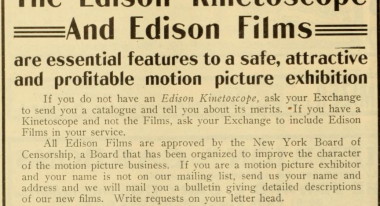

Prior to the publication of the Motion Picture Production Code in 1930 (often called “the Hays Code” after Will H. Hays, its chief enforcer until 1934 when Joseph Breen took over and began enforcing it with new vigor, inaugurating the Code era) there was The Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America trade association, which, among other things, set guidelines for ensuring that films had a “clean moral code.” But prior to that there was a patchwork of censorship strategies, some arising at the state level, others city by city. In 1909, in New York City, The New York Board of Motion Picture Censorship (changed to The National Board of Review in 1916) was founded partly in response to the actions of Mayor George B. McLellan, Jr., who had revoked the exhibition licenses of every venue (around 550) where films were shown in the city. During its first several years the New York Board of Censorship gave at least the outward appearance of working. Motivated by fears that other politicians might, following the lead of Governor McLellan, revoke exhibition licenses, most of the film production companies submitted their films to the board, and proudly announced this fact, as in this Edison Films promotion from the 1909 issue of Motion Picture World.

In 1915, the Supreme Court affirmed, in Mutual Film Corp. v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, the legality of a state board of censors, opening up the door for other states to follow suit. Movies, the Court maintained,

may be used for evil, and against that possibility the statute was enacted. Their power of amusement, and, it may be, education, the audiences they assemble, not of women alone nor of men alone, but together, not of adults only, but of children, make them the more insidious in corruption by a pretense of worthy purpose or if they should degenerate from worthy purpose. Indeed, we may go beyond that possibility. They take their attraction from the general interest, eager and wholesome it may be, in their subjects, but a prurient interest may be excited and appealed to.

It’s the mixed nature of the audiences–“not of women alone or men alone, but together”–with children as well, that seems offensive to the Justices. In fact, it’s not necessarily the content of movies that’s considered potentially dangerous, but rather the unanticipated consequences (whatever those may be) of different sexes and age groups mixing together, sharing a common experience that may, in fact, appeal to their prurient interests.

Of the thousands of articles and notices about censorship that appear in the pages of film magazines from the teens, I’ve selected several that indicate the wide range of thought at the time. It’s a fascinating, chaotic decade in the emergence of film, a good 15 to 20 years before the more familiar Production Code gained real force, and before the ratings system largely put an end to talk of film censorship in the United States.

The articles are a rich source of ethnographic history of the thousands of local censorship boards. In almost every instance references to the these board indicate that they were of mixed gender, with more than a half-dozen or so specific mentions of all-female boards. A typical is this news item from a 1912 issue of Motography, under the headline “Baltimore’s New Censorship Plan”:

A board of seven men and women, to serve without pay, is the new plan for the censorship of moving pictures suggested by Councilman Harry C. Kilmer, of Baltimore, Md. Mr. Kilmer wants to board to have three paid assistants, one a secretary and the other two detectives to catch violators or the law among moving picture theater owners.

Among the many problems that plagued local and state censorship boards–ranging from enforcement difficulties, funding the boards, assuring continuity as members rotated on and off, legal threats to their existence–the one seized on regularly by anti-censorship advocates was corruption. Graft, plain and simple. There were some notorious cases involving payment for services, um, “rendered,” to wit here’s a few dollars and oh yes your seal of approval would be nice. This, for instance, is a notice from the “Facts and Comments” column in Moving Picture World, 1912:

Hit a reformer a light blow from the hammer of truth and you will often penetrate the outward semblance and reveal the plain and shocking outlines of what is commonly called a grafter. A person named H.P. Frey appeared on the moving picture horizon a short time ago, preaching the gospel of superior censorship. He had selected the good, old town of Reading, Pa., for the field of his activities and he soon made the welkin ring with his loud cries of reform. According to reports of Reading papers it now appears that Frey was willing to sell the sanction of his committee for small sums of money.

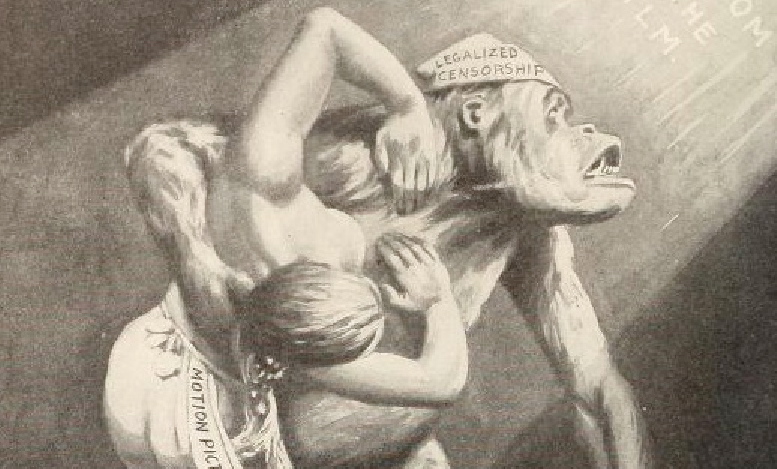

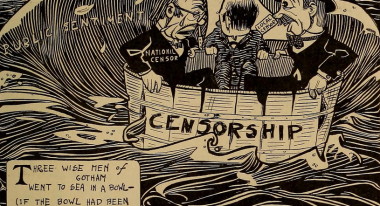

The magazine Photoplay tended to publish the most lively and scathing anti-censorship editorials and cartoons, some of them referencing social and cultural trends and topics of the day that had nothing to do, per se, with censorship at all. One of the most fascinating of these is an editorial from May 1918 which targets the “short-haired” women of censorship boards, most likely a reference to the bob hairstyle fashionable at the time, and which had been introduced by dancer Irene Castle several years earlier. Here’s an excerpt from “The ‘Don’t’ Men,” with a detail from the accompanying illustration:

The average censor is a “Don’t” man. He is a destroyer. He is a coward, afraid of life, afraid of truth, afraid of his own shadow. . . . Censorship boards, in the main, are composed of short-haired women and long-haired men–sterile types. Who is there that knows a short-haired mother of a fine, vigorous, American family? Who is there that knows a long-haired man who is fit to be the father of a Boy Scout? They are the social drones, the women apeing the men and the men apeing the women, until they are neither women nor men, but flabby nondescripts, ripe for appointment to censorship boards.

Yet many columns also offered a more subtle reading of the effects of censorship, as in the 1917 Photoplay column “Making Plays for Censors,” which suggested that one of the devious consequences of censorship was that it impacted the content of movies in unconscious ways. In this respect, the argument closely resembles the theorist Antonio Gramsci’s notions of hegemony and the ways in which power is not simply imposed from above, but has to be won through the subordinated groups’ spontaneous consent to the cultural domination which they believe will serve their interests because it is “common sense:”

The manufacturers are making plays [movies] for the censors, consciously or unconsciously. Plays made for the censors are not plays made for the public, the critics, or the hopeful connoisseurs of new art. Such plays are not plays at all, or anything else save shapeless, mindless pictorial invertebrates. They have been stripped of vitality in order that their boneless carcasses may be squeezed through the republic’s twenty or more censorial sieves of different mesh.

In fact, like the Production Code that was to come–which offered a complex, pre-“cultural studies” model of media theory that recognized how motion pictures did not merely reflect social reality, but in fact helped to create it–some defenders of censorship recognized that what it was really about was the intense imaginative collaboration between film and audience. Here is Clarence M. Abbott, a member of the National Board of Review, from an essay called “How they ‘Censor’ the Films” in Motion Picture Magazine, 1916:

The test of sincerity is frequently applied to action which is questionable. Themes may be made immoral when their true importance in the relations of society is ridiculed and shown in a farcical or burlesque light. Marital infidelity, degeneracy and sexual irregularities are notable examples. On the other hand, a plot developing in whole or in part about infidelity may be employed, if its character is serious and if in the end good is rewarded and evil punished. Pictures must be judged as a whole, with a view to the total effect upon the audiences.

Although the apparatus of motion picture censorship would organize and grow teeth by the 1930s, some of the most entertaining attacks on it used humor as a weapon.The London-based magazine Pictures and the Picturegoer, in particular, brought a deep-history perspective to the practice. This, from a 1915 issue: “‘All comedies must have a serious purpose,’ recently declared the Censorship Boards of Pennsylvania and Ohio.” The article continues by imagining what would happen if the censorship codes were applied to Shakespeare, with imagined results like this:

TWELFTH NIGHT–Not approved. The strange mixing of the sexes leads to immodest thoughts.

KING LEAR–Not approved. This play is a grave menace to the family life and the homes of Pennsylvania and Ohio.

MACBETH–Not approved. This play visualizes several murders in the first degree and a shocking suicide committed by a woman.

EXTRAS:

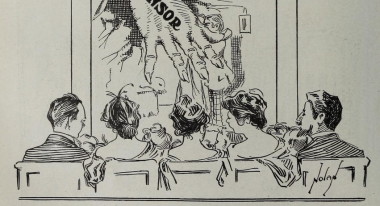

As censorship boards often invoked the protection of children as justification for censoring motion picture content, many editorials and cartoons questioned this as a justification for censorship, as in this 1914 illustration from Motion Picture Magazine:

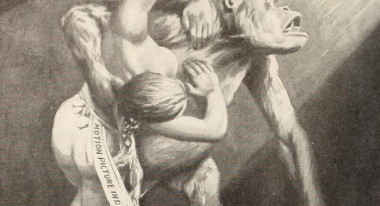

The full version (click to enlarge) of the “ape” header image at the top of the post, from Film Fun, 1916: