Back to selection

Back to selection

Railway Ties: The Golden Dream

The Golden Dream

The Golden Dream Like us, objects and events can be photogenic–or not. Boxing matches, galloping horses, and speeding trains, for example, have proven ideal fodder for the motion-picture camera. The last of these subjects is also the oldest, going back to the pioneering Lumiere Brothers’ doc, The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat. It was made and first shown in 1896, the first year that film was projected. The narrative of this 50-second actualité is simple. A train pulls into the station and stops; anonymous passengers disembark with the help of people standing on the platform, a few of whom then climb aboard. It’s all perfectly civil.

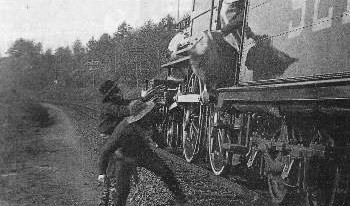

The Lumières sensed the compatibility of iron horse and celluloid. In 1903, on the other side of the Atlantic, Edwin S. Porter directed The Great Train Robbery, a much longer narrative with a Wild Western twang that takes advantage of the star power of the train. The scenario is jam-packed with highly uncivil characters, who are portrayed by real actors. We first see the moving train through the windows of the manager’s office, adjacent to the platform, while the fellow is being held up at gunpoint. Cut to something akin to a reverse shot: a view from one of the cars, its door wide open, that captures the changing landscape. The villains inside the car shoot the conductor; the train keeps going. (You must remember that the conventions of what became known as classical film editing were yet to come. Successive scenes often occur simultaneously.) It makes a pit stop to take fuel through a large pipe that bisects the space just above the train and attaches to a huge, very high storage container. It continues onward.

Variations on these scenes still appear 120 years later in movies set primarily on trains. An extraordinary example is The Golden Dream, aka La Jaula de Oro (The Golden Dream), a 2013 Mexican film just now opening in the U.S. Directed by first-time feature filmmaker Diego Quemada-Díez, a native of Spain and longtime resident of Mexico, it is a welcome addition not only to the genre, but also to a new subgenre comprised of pictures about young Latin American migrants who hazard the rail journey to El Norte. (La Jaula de Oro translates literally into “The Gilded Cage”–the name of a ballad about the despair of those who have made it to the States but are captives of menial jobs and indifference, at best.)

I don’t think it’s a stretch to claim that the mise-en-scene of the rather gratuitous refueling scene in The Great Train Robbery anticipates The Golden Dream’s frequent slicing of the frame by architectural elements such as bridges and tunnels. The structures aid in anchoring the newer film, as do well-timed scenes of 16-year-old protagonist Juan (Brandon Lopez) wandering center frame in an exaggerated state of loneliness down railroad tracks, country paths, and dusty village roads; punctuating POV shots from the top of the train of natural landscapes, including deserts, mountains, snow, lakes, groves, and arid plains; and inserts of decaying edifices, many from the colonial era, in towns and rural spots when the train comes to a halt. Quemada-Díez seems to fear monotony. He lightens the film’s dark sensibility with scenes of performance — busking in Hidalgo, dancing at a sugar cane plantation during a forced-labor stop — and hilarious sequences, such as Juan’s clumsy attempts to subdue and kill a rooster for dinner.

The kind assist strangers offer passengers emerging from the interior in The Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat foreshadows the camaraderie and reciprocated help (most of the time) that grows among bunched-up riders sitting and lying on the precarious rooftops in The Golden Dream. The violence in Porter’s seminal film, on the other hand, is a precursor of the flip side of that friendly behavior: the horrors suffered by the desperate young travelers.

Two films by American directors, both from 2009, come to mind. Rebecca Cammisa’s Which Way Home stems from the Lumière doc tradition; Cary Joji Fukunaga’s Sin Nombre, from the Porter fictional school. Both pictures add a socially conscious, non-anglocentric spin to the train movie, while touching on that generic staple, the teen film. The mix forms the foundation of such a masterful elaboration as The Golden Dream.

Sin Nombre is a rigorous observation of the long journey through the eyes of young people from two different circles. Fukunaga aestheticizes without excluding the inherent extreme roughness of the, well, rite of passage: a loaded but valid term at this point. A well-made, less flashy film, Which Way Home eschews screen violence altogether, except for descriptions in on-camera testimony from migrants speaking inside shelters and detention centers. Cammisa broadens the expanse: Families grieve over the graves of children who did not complete the trip.

Quemada-Díez takes another approach. His film is taut, the drama packed neatly and efficiently into the lengthy, perilous odyssey. A former assistant to Ken Loach, he has appropriated the director’s signature style in mostly British films about the impact of social and historical events on the individual. Loach’s acolyte writes, “Behind migration there is colonization…one person or a group that occupies the land of another to exploit it and to exploit others.”

Like Loach, he shoots in chronological order on actual locations, using natural lighting. No zooms, dollies, or crane shots. The performers are nonprofessionals. He gives them space for some improvisation. Quemada-Díez did not, however, allow his three leads to read the script. He spoke with them about each scene just before filming it.

He builds a marvelous, contagious rhythm with some non-Loachian strategies. With ellipses and jump cuts, he varies the form and content of sequences that take place on the multiple trains. For example, one might show the process of jumping on, the next beginning in media res with the youths already settled on the roof, the following one starting just at the moment a heavily dramatic event, such as a robbery, takes place. He alters shot types, deploys brisk montages of exterior vistas, and swings back and forth between bright light and near-total darkness.

Operating in tandem with the visuals is a superb minimalist soundtrack. Composers Leonardo Heiblum and Jacobo Lieberman shift among ambient noises, complete silence, and music from heavy single piano keys, guitar, a bit of melancholy vocal, and cello, Rodrigo Duarte playing two powerful solos at significant narrative spots. (The credits also list the instruments jarana, copas, cuenco Tibetano, and cuenco de cuarzo.) I think Quemada-Díez is afraid of ennui, at least where spectators are concerned.

The genesis of The Golden Dream dates back to a two-month period in 2003 when the filmmaker lived in Mazatlan, next to the railroad tracks. Every day he met new migrants, who described in detail the nightmare passage. Quemada-Díez writes about the position he has taken for his film, one that foregrounds the unique nature of their quests.

Many died. Nevertheless they chalked it up to experience, with the idea they would be making money and sending it to their families, sacrificing their lives for the people they love. It seemed to me they were heroes, that their stories were like epic poems, their journeys metaphors for life—an extreme dramatization of human existence….I met some wonderful people who taught me a lot of things, including generosity and the value of brotherhood.

He condenses 500-600 stories into the tale of three Guatemalans headed for Mexicali and Los Angeles. Juan is the self-centered, bossy, and suspicious self-designated leader of the group. His temper and limited intellectual range are at odds with his youthful vulnerability. Attractive in an ordinary way, Sara, aka Osvaldo (Karen Martinez), also 16, is a giving, curious friend of Juan’s from home who disguises herself as a boy in the dubious hope it will make the journey safer. In a wonderful scene behind a door marked “Damas,” she cuts her hair, dons a baseball cap, and wraps her breasts tightly with adhesive tape.

She becomes negotiator for Juan and a third teen, mop-haired Tzotzil Indian Chauk (Rodolfo Dominguez), a mellow, practical, and affable youth who, sensitive product of his own subculture, is a pantheist humanely oriented toward the common good. (The Tzotzil expression for our “How are you?” is “How is your heart?”) Unfortunately, he doesn’t speak a word of Spanish. The issue that requires diplomacy? Sara herself, of course, especially after she reveals her secret to the susceptible Chauk, totally inexperienced in matters of sex and love.

A fourth character, Carlos Chajon’s Samuel, drops out of the expedition following their first major hurdle: a bust by corrupt Mexican cops. He returns to Guatemala to resume combing a landfill overrun by vultures for objects to sell. Juan stays on, despite the police pilfering his beloved macho boots, as does the wounded Chauk, who reveals a hidden antiauthoritarian streak when he fights back ferociously. Sara continues as well, in large part due to her feelings for Juan.

Neither beauty nor cutie, principals Sara and Chauk maintain their relatively stable personae throughout the ups and downs of the trip. Juan is the most interesting and engaging character, like the off-beam neurotics in Douglas Sirk films. Trying events determine that he alter his sense of self and attitude toward others. The youths endure the hell of robbery, kidnapping, and forced smuggling at the hands of career criminals, as well as excessive force by thieving, power-mad soldiers in Mexico. At each border, they are confronted by the Migra, immigration authorities who chase them down for deportation.

These kids are constantly running. Preying on them are not only duplicitous coyotes, but also, sadly enough, some of their own, who coax them into dodgy situations solely to earn a few pesos. All of this leads up to car, boat and helicopter patrols on the U.S. side of the border. Being kicked out isn’t as bad as the fate awaiting some, courtesy of anti-immigrant sharpshooters hiding on the side for which these ambitious kids gave up everything.

There are some terrific life-affirming actions, but they don’t come close to cancelling out the negatives. Youths and their parents toss fruit and bottled water up to the riders. More formal help comes through the system of hostels and feeding stations. Many are run by priests and nuns; others, by human rights organizations. Most heartwarming, however, is the blossoming camaraderie already noted, which becomes more and more palpable as the adventure goes on. Sharing what little they have or find becomes second nature. The rituals are functions of necessity and, hopefully, salvation.

The final credits list a plethora of locations, including two cities in Guatemala, approximately 10 Mexican states, and, in the U.S. Long Beach, L.A., and Jackson Hole, Wyoming. (This is a train trip, after all, plus the director obviously wanted to diversify the footage.)

What impresses me most in these ultimate litanies is the wide range of “thank yous,” which in the case of artists’ names must translate into favorites and influences: from Latin America, such filmmakers as Mexico-based, Spanish born Carlos Reygadas, Chilean Alejandro Jodorowsky, Colombian Oscar Ruiz Navia, and Brazilian Fernando Meirelles, as well as Mexican DP Rodrigo Prieto; and, from outside Latin America, a wide array of directors that includes Spike Lee, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Pier Paolo Pasolini, George Stevens, Gillo Pontecorvo, Michael Winterbottom, and, of course, Loach. One surprising recipient of gratitude, however, never touched a camera: Robert Louis Stevenson. Ho-la!