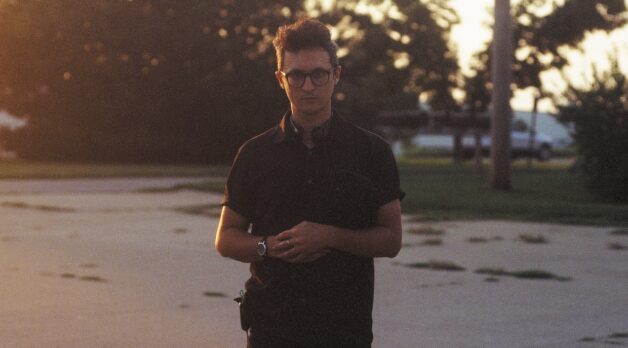

Philip Rabalais

Philip Rabalais

Philip Rabalais

“I’m haunted by this question of, ‘Is my work experimental, or is it narrative?’” says Philip Rabalais. “But I also find a lot of energy in this.” Take his latest short, Moonroof, which begins as though a more sedate Beavis and Butthead were transplanted into a seat-POV-restricted variation on James Benning’s Ten Skies. Two heard but not seen male voices look out while asking each other a series of tenuous A-or-B questions (“Would you rather be a car or a very deep hole?”), their gaze restricted to the titular portal. For the lysergic finale, that moonroof unexpectedly detaches itself from the vehicle, as what begins as an extended joke in an unclear direction ends as almost a sculptural installation.

Moonroof, which premieres in October at the Drunken Film Fest Oakland, is the latest in a series of shorts Rabalais has made over the past 10 years. His first interest was making electronic music, which he began in high school and “got much more serious about after college. I pursued it pretty intensely for a decade in a band, Utopia Park.” The name came from the trailer park in Fairfield, Iowa, where Rabalais grew up. (The small midwestern town became a hotbed for Transcendental Meditation in the 1980s, when his parents moved there.) When he “hit the existential point with music where I didn’t know where to go” with it, his brother (and, previously, bandmate) “had his own solo project going, and his aspiration was to make 40 music videos in a year.” Video editing came “somewhat naturally,” Rabalais says, “because nonlinear editing is very similar to music production. So, I started helping him by making films, and now it’s been another 10 years.”

Both Rabalais’s first short film, 2016’s Bobby Alaska and Donny Breadsticks in Heaven, and Moonroof received grants from the Iowa Arts Council. By and large, though, his output is self-financed. “I run a very small video production company,” he explains. “I am below the poverty line because all of my extra income from the business goes into self-financing these little projects.” Production design, he notes, is “conceived based on what we have access to.” On Moonroof, “We built an eight-by-eight, highly overengineered giant lazy Susan that we put the moonroof on. This is all from the scrapyard. Then, we bought two car seats and built them onto those poles. I think it would have cost $1,200 to rent a circular dolly track; it cost about the same just to build a giant lazy Susan. Every project has had some sort of guiding experiment or dare, and in that one it was, can we build this absolutely nonsensical set piece?”

Forthcoming projects include Rabelais’s first feature, The Tower of Invincibility, co-written and -directed with Auden Lincoln-Vogel, a longtime creative collaborator who’s operated in many different crew positions. “We’ve been shooting it in little bits and bobs—I think we’re going to hit the two-year mark in September,” Rabalais says. “It’s a sprawling portrait of Fairfield in the spirit of Gummo or Stalker.” And it’s a film that, like his work in general, Rabalais believes benefits from his remaining in the midwest: “I have a buddy who went to USC. He’s also from Fairfield, and he was trying to to persuade me to move to L.A. His metaphor was, ‘Making films in the midwest is like trying to climb a mountain without an oxygen tank or the gear.’ And while I understand and appreciate that metaphor, I have found a community in Iowa of enough filmmakers that we can make this weird, sprawling feature film with a few really close collaborators. We shot a scene in a bar. We paid the bartender $100—we were there all day. That was the entire location fee. The whole thing cost probably just over $1,000 for a pretty sizable day shoot. Despite what we lack in resources, we have the tenacity to take advantage of what is around us.”—Vadim Rizov/Image: Ace Boothby