Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Choosing the Alexa 65 over Film and Finding the Right Format: DP Greig Fraser on Lion and Rogue One: A Star Wars Story

Greig Fraser on the set of Lion

Greig Fraser on the set of Lion It’s fair to say that 2015 was a pretty good year for Greig Fraser. The cinematographer globetrotted to London, Jordan, Iceland, the Maldives, India, and his native Australia while lensing two movies. One of them (Lion) has Fraser in the Oscar conversation and the other (Rogue One: A Star Wars Story) is a blockbuster prequel to his favorite childhood films.

The two movies seemingly couldn’t be any more different. Rogue One is a space adventure with a $200 million budget and a small country’s GDP worth of merchandising revenue in which the final half is basically one intense battle sequence. Lion is a based-in-truth dramatic tearjerker in which the film’s final half frequently features a man on his couch searching Google Earth from his laptop. But there are similarities. Narratively, both follow protagonists searching for long-lost families. Technically, both are shot with Arri digital cameras and both leaned heavily on Digital Sputnik LED lights. And, of course, both are shot by Fraser.

With Lion and Rogue One simultaneously out in wide release, Fraser spoke to Filmmaker about shooting the entirety of his Star Wars prequel on the Alexa 65, using The Hateful Eight’s lenses, and how his grips ended up dressed as Indian railroad employees.

Filmmaker: We’re about the same age and I distinctly remember seeing Return of the Jedi in theaters and then wearing out the original films on VHS. What was your relationship with Star Wars growing up?

Fraser: The only one that I actually saw in the cinema was Return of the Jedi, but I saw the others [on home video] and I can’t recall any other films that I liked more as a kid. I had all the toys as well — all that my family could afford to buy me or that I could afford to buy for myself.

Filmmaker: Were your kids old enough to appreciate that you were working in the Star Wars universe?

Fraser: My wife and I actually had a baby while we were filming, but our other two boys kind of had an idea. They got caught up a little bit in the hype when The Force Awakens came out, so there was some sense of “Oh, you’re doing Star Wars,” but they were a little too young to really get it. The other day I did order Rogue One sticker books off Amazon – which are exactly like the sticker books that I had from the original films – and it was fantastic to see my boys enjoying those.

Filmmaker: In terms of making Rogue One, the Alexa 65 seems like a good place to start, since the movie holds the distinction of being the first entirely shot with Arri’s large format digital camera. I know you tested it against a variety of other possibilities, including film. What were you looking for in those tests?

Fraser: We tested it against 35mm film, 65mm film, and 35mm digital sensors. There is a whole range of things you look at when you’re deciding on a format for a movie. Film is beautiful, but there are other considerations that go along with film, like the inability to shoot longer takes. [Rogue One director] Gareth Edwards is very much the type of filmmaker that likes to shoot continuously. He’ll speak to his actors mid-take and then reset them and have them do it again rather than cutting the camera. He also often likes to operate his own camera handheld, which I think is fantastic, frankly, because it means that I can concentrate more on the lighting knowing that he’s happy and getting the shots that he needs.

Filmmaker: Do the 65mm film mags come in the same 1000-foot and 400-foot loads that are typical for 35mm?

Fraser: Yes, but they’re very large, which is another factor. It just didn’t seem like a viable option to shoot film for Rogue One. Some filmmakers like to choose the format first and then make the style work with that format. I like to choose the style first and then figure out what format suits that style.

Filmmaker: I was reading up on the Alexa 65 for our talk and it looks like the two terabyte capture drives give you about 40 minutes of footage – and on the big action days I imagine you had quite a few cameras rolling. Do you have any idea what your media totals averaged for a day?

Fraser: No, I kind of left that stuff to the post company, Pinewood Post, who did all of our dailies and data wrangling. I must say, they were just an incredible facility. I do remember really early on, when we were doing the camera tests, we were initially talking about doing some shooting on 35mm and then some Alexa 65. After all the testing everyone was like, “Okay, so how much Alexa 65 are you doing and how much 35mm?” And I said, “Well guys, I actually think I’m going to shoot the whole thing on the Alexa 65.” The faces of the people from Pinewood Post just went white. They knew that the data from a full 65mm show was going to be insane. I said, “I’m confident you guys can handle it, right?” And they said, “Yeah, we can absolutely handle it,” but I remember they looked slightly nervous, like they’d just eaten something that was not quite right. (laughs) That was in November of 2014. Flash forward to a year later as we were nearing finishing principal photography and not only had they done all the data on Rogue One, they were doing data on Assassin’s Creed and Doctor Strange. So not only did they handle our entire show with multiple units going and multiple cameras, they handled two other shows as well.

I remember on Zero Dark Thirty we were talking about shooting ProRes vs. Raw and there was discussion about Raw being so much more data. Now you wouldn’t even discuss it. It’s normal to shoot Raw. The point is people get a bit terrified of the unknown, but then once you start doing it you figure it out and it becomes normal.

Filmmaker: For lenses you selected some of the same Ultra Panavision 70 anamorphic glass used by Robert Richardson on The Hateful Eight.

Fraser: When Bob and his 1st AC Gregor Tavenner were putting together those lenses and having them rehoused [in preparation for The Hateful Eight[ I saw the lenses. Some of them were really not appropriate for us: they were large, they were flarey, they were not good handheld lenses. They were studio-based, tripod-based lenses. But there were a couple that I thought could really do the job for us. So I suggested we do a little test on them before they went and shot The Hateful Eight. We couldn’t shoot the test on digital because there was no mount [for the lenses for any digital cameras] at that point, so I shot the tests on film. Then I put that footage together with the camera tests I did in London [for Rogue One] and said, “I think [the Alexa 65 and the Ultra Panavision 70 lenses] would work really well together.” So we got started working with Panavision and Arri to make the cameras and lenses work together. I don’t know technically what they needed to do to make that happen, but it was a fantastic effort by all concerned to get these two completely different systems in Arri and Panavision playing together. But those lenses are by far the very best lenses I’ve ever used.

Filmmaker: Did you have enough of them to go around for some of your bigger days when you had multiple cameras going?

Fraser: There certainly was not an abundance of those lenses, I can tell you that for sure, but we figured it out. We had two sets of lenses and for the big action scenes we never had more than four cameras going at once. So we really never had a shortage of lenses. One thing about the 65mm format that people forget is that you can crop into it, because you’re never finishing the movie in 6.5K. The most we’re going to finish at right now is 4K. So you can crop into the sensor quite a way and still end up with 4K images. If you’ve got a 65mm lens you can crop 60 percent and end up with the equivalent of like a 95mm lens. So sometimes rather than changing the lens, we would change the crop to get a different size.

Filmmaker: As a bridge over to Lion, tell me about these Digital Sputnik LED lights that were workhorses on both films. You shot Lion first. How did you discover them for that shoot?

Fraser: Even though I shot Lion first we did all of the preparatory work for Star Wars before I shot Lion, so we had access to some brilliant lights to test from Creamsource, Digital Sputnik, and LiteGear. And we said, “You know what? We could probably do this entire movie with these lights if we got enough of them.” Luckily we had a long lead time — we did those tests in November of 2014 and principal (on Rogue One) didn’t begin until May or June of the following year — so that gave us time to be able to say to manufacturers and rental houses and to production, “We’re going to try to save money on power, on rigging, on consumables like gels and other things by using these lights, but here’s what we need to do that. We need 50 of these lights, 100 of these lights, 200 of these lights.” That all happened before Lion happened.

Then when I took my Star Wars cap off and started prep for Lion I thought, “What lights would be the best to take to India that are small and will allow us to move really quickly?” And you know what, it was the same lights. The way we used them was different — we controlled them with wi-fi [on Lion] rather than with DMX [like on Rogue One] — but effectively they’re the same lights. That just blew my mind and opened up the possibilities for what you can do with LEDs.

Filmmaker: I’ve never seen those lights before. The DS6 looks like a rig with a bunch of little Maxi Brutes on it. How big is that unit?

Fraser: A foot-and-a-half by two-feet, maybe? Each of those little heads is I think 4″-x-4″.

Filmmaker: So you could point each of those six heads on the DS6 at a different spot? Is each individual head powerful enough to carry very far on its own?

Fraser: Yeah they are. That’s why I was really excited in 2014 when we tested them. The soft LEDs [made before then] — Litepanels and all that stuff — didn’t have a lot of output. All you could really use them for was augmentation. You couldn’t light entire scenes with them because they weren’t powerful enough. But now these new LEDs have this higher output in addition to the ability to change color, so you don’t need to use gels.

Filmmaker: You can control the color and intensity of each DS6 head via your iPad. Can you move the position of the head remotely as well or does someone still have to physically adjust it?

Fraser: There’s no motorization of the heads.

Filmmaker: That would be a nice feature.

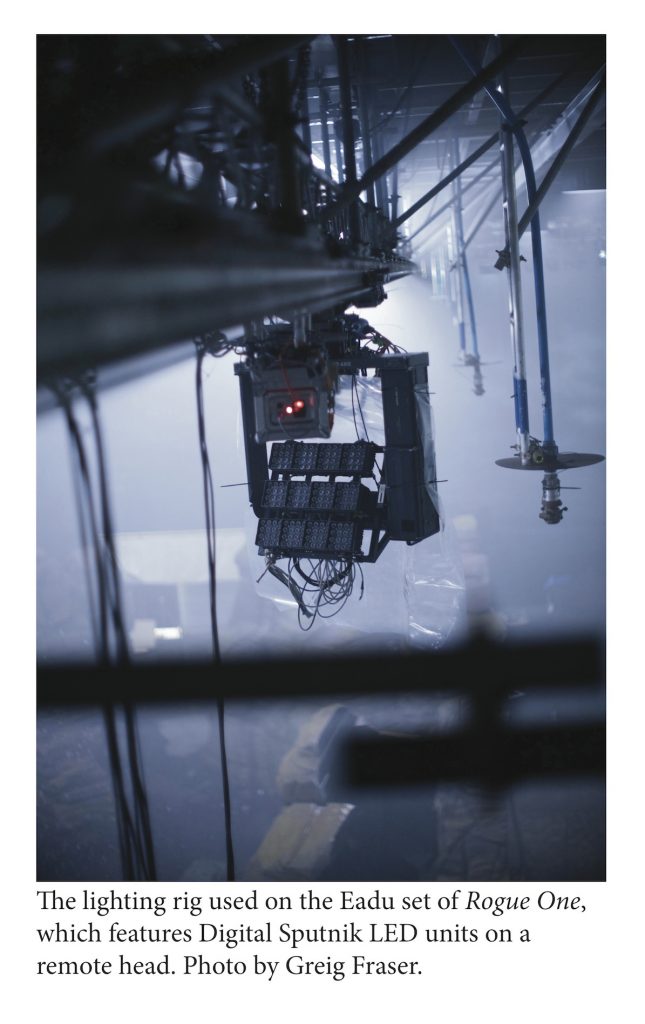

Fraser: Wouldn’t it. That would be amazing — though it would be a whole new layer of hurt when they weren’t working properly. We actually did do something kind of like [a motorized head] on Star Wars. On the Eadu set, which is the rainy planet [where heroine Jyn Erso travels to rescue her father], there are a number of times that lights come over the set. The first time is when Krennic’s ship comes in and again when some X-wings arrive. So we put some Digital Sputniks side by side on a remote head [normally used for a camera], and then the special effects guys rigged a wire cam into the ceiling that could go from one end of the stage to the other. With the remote head, you could angle those lights to point wherever you wanted. Those lights together could create a single beam that looked completely and utterly believable. It was a really fantastic rig because it had that intensity and then we could change the color [remotely]. So we started them dimmed down and more blue, and as we panned the light and moved the rig across our set we changed the color temperature slightly and changed the intensity to make it appear that the ship was getting closer.

Filmmaker: You had a much less high-tech rig at the train station in Calcutta on Lion, where the film’s protagonist Saroo is lost as a young boy after falling asleep on a train. You hid the camera in piles of shipping boxes to be more inconspicuous.

Fraser: (laughs) We tried really hard to blend in while we were in India, but I don’t look Indian at all, nor does my crew. We were pretty much all Australian and it’s already hard to blend in when you’re in India with a camera strapped to your shoulder. Wherever we went, people wanted to know what we were doing and people wanted to stare at the camera. It’s a natural reaction, but it’s a hindrance when you’re trying to shoot naturally. At every Indian train station there are always boxes covered with hessian [fabric]. The train system is essentially the arteries of India’s commerce and goods are shipped on it all the time. We made a couple of hides that looked like [carts with] cardboard boxes on them covered with hessian, with a little flap in the front. So we’d go to our little safe area around the corner and climb in with the camera and then a grip would dress like one of the guys who help at the train station — I think they’re called pulleys — and wheel us out. I’d be on the radio saying, “Okay, forward. Stop. Camera right. Stop there.” Then we’d lift the flap and stick the lens out. People did see us, but it was not very many people and not until we got close to them. There’s this great shot that we managed to get of Saroo climbing up over the heads of all the other passengers and we wouldn’t have gotten that shot had all those passengers seen the camera. So there was a lot of covert shooting going on.

We did something similar on Zero Dark Thirty. There’s a scene where we were walking with Jessica Chastain’s character through a market as she’s buying groceries and we couldn’t get any privacy. Everyone was staring at what we were doing. So one of my grips went three aisles over and literally did a song and dance and we had another camera pretend to shoot him. Everyone flocked to watch this grip and we were able to go through the market and get the shot of Jessica that we wanted.

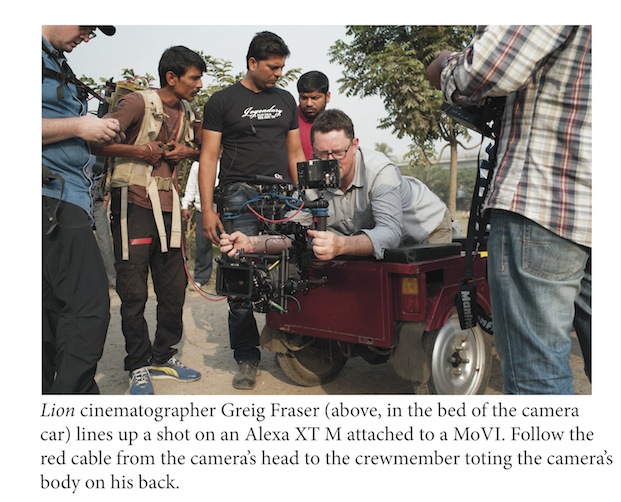

Filmmaker: To have that smaller footprint you went with the Alexa XT M, which is basically broken up into a small head with the lens that is connected to a separate camera body. I’ve seen a few set photos where a crew guy is wearing a backplate with the Alexa M body, a couple V-mount batteries, and a Teradeck wireless transmitter attached.

Fraser: The Alexa Mini hadn’t really come out at that point, so the M was a really great camera for the time. It allowed the Alexa to go on gimbals and to go in really small environments and small spaces.

Filmmaker: For Lion’s lenses you went with Panavision PVintage primes, which are re-housed Ultra Speeds from the ’70s.

Fraser: Panavision had a lot of these cool old lenses that were not really up to today’s standards of markings and housings. Everybody now expects the same size front and markings on both sides, and [the Ultra Speeds] didn’t quite have that because they were built in a different era. I’ve been using the Ultra Speeds for a long time, ever since I was a young cinematographer. They were always at the bottom of the pile. Everyone wanted the new Panavision lenses — which at the time were the Primos — but I always loved these really old ones. So effectively the PVintage are those same Ultra Speed lenses, but they’ve been made more production friendly and more AC friendly. It’s a really lovely set with a nice feel to them.

Filmmaker: You talked in another interview about “finding the right stop” for each film. Tell me about that process.

Fraser: It depends on the taste of the filmmaker. [Lion director] Garth Davis is very much not a shallow focus lover. He feels that it becomes a little bit distracting for his movies, so when we could we tried to give a bit more stop to help the audience be in the environments a little bit more. [Rogue One director] Gareth Edwards wanted less depth of field. Rogue One has more handheld and more camera movement and Gareth wanted more focus falloff. Each filmmaker is unique, and that’s what I love about working with different directors.

Matt Mulcahey writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.