Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Pink Skies and Poetic Artifacts: DP Linus Sandgren on La La Land

Early in La La Land, Emma Stone’s aspiring actress rises from a restaurant conversation about the unpleasantness of contemporary moviegoing and sprints to the Rialto Theatre to take in Rebel Without a Cause with Ryan Gosling’s intractably traditionalist jazz pianist. The burst of exuberance doesn’t last. The Rialto later closes down and as Gosling waxes poetic about jazz’s declining cultural relevance you begin to feel that for La La Land jazz is just a surrogate for the state of film itself. La La Land is an ode to the magic of movies – at a time when going to the movies has rarely felt less magical. But I’m not going to prattle on with another “Do Movies Still Matters” diatribe. I can only say that they certainly still matter to me. And that La La Land served as a reminder that there’s still an indefinable alchemy found within a great movie that isn’t replicated by any other medium.

Because so much has already been written about La La Land’s dazzling musical set pieces and the work of cinematographer Linus Sandgren (American Hustle, Joy), I did things a little differently than usual when I chatted with Linus. I didn’t spend time going over cameras and lenses – you’ll find a summation of that tech info below – and instead focused on details that I hadn’t read about yet. Which is how I ended up asking Linus Sandgren, “But where did you put the toilets?”

Camera: Panavision XL2 (the flashback sequence at the film’s conclusion features a bit of 16mm footage shot on an Aaton A-Minima N16).

Film Stock: Kodak Vision3 500T 5219 and 250D 5207. For finer grain and softer contrast, Sandgren pull-processed the footage one stop.

Lenses: Panavision C series and E series anamorphics. Panavision customized the C series 40mm lens to achieve a minimum focus of 19 inches – much closer than a typical anamorphic lens.

Filmmaker: I love the movies of the Hollywood studio era that La La Land harkens back to, but I always gravitated more toward film noir and westerns rather than musicals. How familiar were you with that genre before taking on this film?

Sandgren: I had seen a few of the classic ones, but I hadn’t really watched a lot of them. I certainly hadn’t dived into them the way [La La Land director] Damien Chazelle had.

Filmmaker: Of the films that Damien had you watch for research, did you have a favorite? Not even in terms of influencing La La Land, but which did you personally connect with?

Sandgren: The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Jacques Demy’s work is very impressive — so unique and unconventional. He had his own vision and I don’t think he really cared what other people thought. He just did what he thought was right. Damien opened up those possibilities for us as well – the possibility to do whatever we felt was right for the story and for the moment without worrying about conventions.

The Scene: La La Land’s opening show-stopper finds the victims of a Los Angeles traffic jam exiting their vehicles and breaking into an impromptu song-and-dance number. Though the shot plays as a oner, it’s actually three separate pieces — two photographed on a Moviebird 45 telescopic crane and another on Steadicam — with the cuts disguised by whip pans. The set piece was filmed over two days on a closed-down ramp connecting the 105 and 110 freeways.

Filmmaker: Even with this being three shots blended together, the camera is still flying around in each of those takes. You’re seeing 360 degrees and you’re on an overpass with nowhere to hide. I saw the film twice and the second time experiencing this scene I started thinking, “I wonder where they hid the focus puller and the crafty coolers and the portable toilets.”

Sandgren: All those things you just mentioned were problems that we dealt with every single day during prep and when we were shooting. It was so hot and everyone needed water all the time — especially all the dancers — and we needed speakers spread out all over so they could dance in synchronization. And then the toilets were far away. (laughs) Thankfully Peter Kohn, the 1st Assistant Director, got the producers to agree to rent that freeway location for a weekend to have a full rehearsal with the [camera] crane and all the vehicles and everything. So we had two days of rehearsals and then we shot the scene two weeks later. It’s a really, really tricky scene. None of the rehearsals were completely right. There was always something wrong until the moment we had to nail it on set.

Filmmaker: Can you break down the logistics of the shot’s three segments for me?

Sandgren: There were so many positive things with that location — it’s like the only place in the city where you can see LA that well from the freeway. It’s surreal. But the negatives were obstacles like the median in the middle of the four lanes, which was very problematic. We had already rehearsed the scene with a Steadicam in a parking lot with cars before we found the freeway location, but we couldn’t run the Steadicam across that concrete median, so we had to rethink everything with a crane in mind. I love that type of puzzle, though. One of the things that’s interesting about being a cinematographer is working out problems like that. The idea of using a drone came up, but it would’ve been impossible to control it as precisely as we needed. Because we had to reach so far with the crane arm the crane had to be moveable. So we used a special trailer that was driveable – basically a motorized dolly platform– and we had to change the shot a little bit to accommodate that configuration.

Two of the shot’s three segments are on that motorized crane and then the third shot is on Steadicam. For the end of the Steadicam shot we hid a crane behind one of the trucks in the scene and when [the Steadicam operator] turned around to follow the parkour dancer, the grips pushed in the crane and [the Steadicam operator] stepped onto the crane backwards and it took him up into a high position. For each of those three moments we shot like 25 takes. Damien is very precise. If one person was out of sync, he wanted to do it again.

The Scene: Ryan Gosling performs “City of Stars” at sunset along a pier. To capture the oner at the perfect moment of twilight, production had roughly 30 minutes to shoot the scene.

Sandgren: What we tried to do in the movie was take these realistic, modern locations and think about them as something more romantic. We felt that gave us a larger freedom to move between the magic in the story and the more real parts of the story. This pier already had those lights that you see at the bottom (near the railing), but then to make this moment more romantic we added these streetlights that were in the shape of old school gaslights, but with the cool white mercury vapor color balance of modern streetlights. We wanted to create colors in the film that we thought were more magical. In Los Angeles there’s a lot of orange sodium-vapor streetlights, but we didn’t want them to exist in our Los Angeles. So we made them cool white colors in combination with the pink skies and blue nights.

Filmmaker: You shot La La Land in the Cinemascope 55 aspect ratio of 2.55:1. When I think of the Cinemascope epics of the 1950s, I think about deep focus. Those movies were intended to dwarf the experience of watching television and they wanted every detail to be sharp. How did you think about deep focus in La La Land? For example, in the bottom pic of these pier frame grabs the background goes pretty soft.

Sandgren: That is where we differ from those old films. We didn’t always have that deep depth of field. We were constantly on like a T2.8 on our lenses. I don’t think we necessarily tried to make a film just like they did back then. We thought of the film as more contemporary. It’s not so preciously done. It’s sort of raw in a way. It’s not so precise. We didn’t care about things like lens flares. My film school teacher would probably say, “Get that out of your lens. Take a French Flag and block it out,” but I think it enhances the image if you look at it in a more poetic way.

Everything is also not so perfectly lit like it would’ve been in [the Hollywood Studio era]. They would’ve used much stronger, harder lights to light up everything so that you could see it perfectly. When [Gosling is on the pier] he’s actually kind of shadowy at some points. We had a little bit of fill on him from a balloon light, but other than that the light comes from those streetlights.

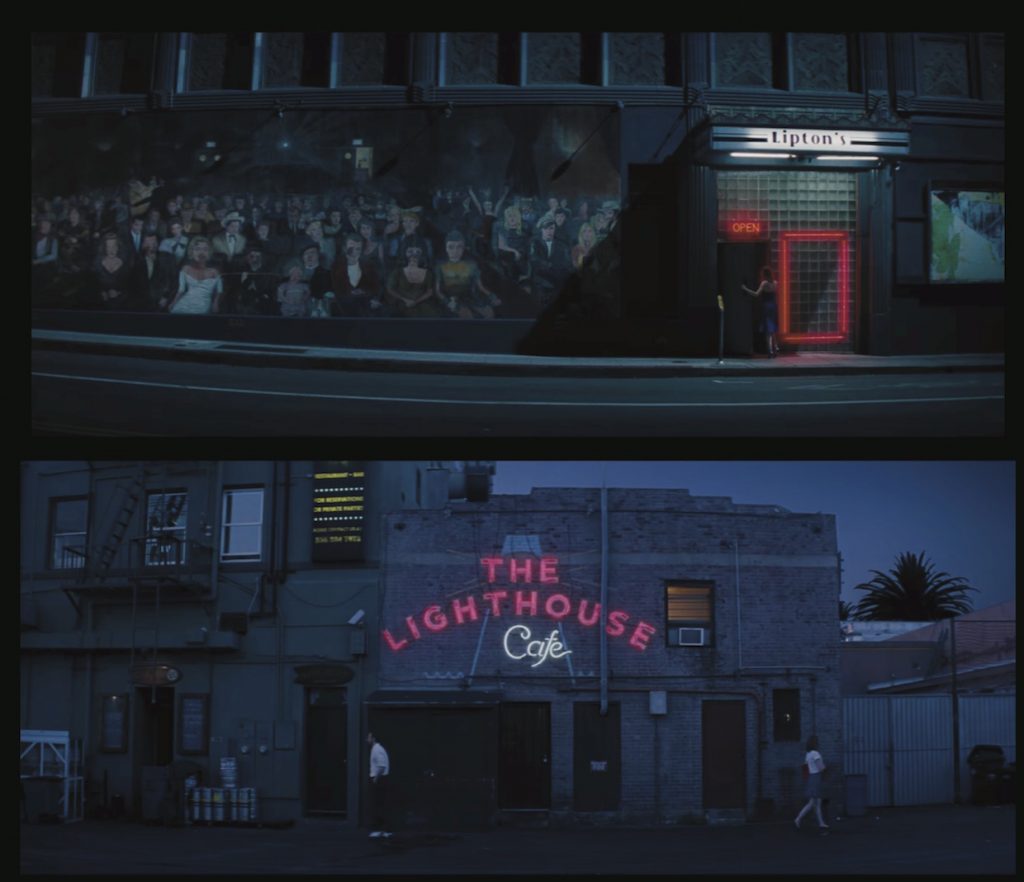

The Scene: A pair of static wide shots at pivotal moments in the romance of Gosling and Stone’s characters.

Filmmaker: There are quite a few incredible camera moves in the film, but I was equally drawn to these static extreme wide shots. They’re not as showy, but I love them.

Sandgren: That shot of The Lighthouse Cafe is one of my favorite shots too, actually.

Filmmaker: You were just talking about the poetry found in imperfections and we see some of that here on the edges of the frame with the barrel distortion from the wide angle lens.

Sandgren: To me it’s easier to express an emotion with imagery if you use those imperfections – things like distortions, flares, and color shifts. It depends on the story you’re trying to tell, but to me those things are more expressive than a technically perfect image. The C Series lenses we used are not technically perfect – if you wanted a technically perfect lens today you would chose something like the Zeiss Master Anamorphics – but we appreciated the poetic artifacts that those old lenses have.

The Scene: Beaten down by the brutality of the audition process, Stone reluctantly goes on one last casting call – during which the lights dim, leaving only a spotlight on Stone as she breaks into song and the camera pushes in and then swoops around her. Stone performed the song live, with composer Justin Hurwitz playing the music on piano in another room, which was then transmitted to Stone via earpiece.

Filmmaker: Is this a Steadicam oner?

Sandgren: Yeah. We couldn’t really go crane in this space. Maybe we could’ve done it on a dolly if we put it on dancefloor, but we went with Steadicam. Ari Robbins, our A-camera operator and Steadicam op, is just incredible. For this shot we cut the table (that the casting director sits at) in half so as Ari starts to move in we could pull the table apart and he could walk through. It’s incredibly hard to keep a shot like that steady when you’re moving in that slow. Then he traveled around Emma with the camera and back again as we pushed the table back together. That was the emotional movement we felt was right for the scene because of the way she sings the song – the way she gets powerful as we pivot around her and then we pull away as we leave her in a sad moment. It’s not a fancy move, but it’s very intimate as we fade out the realistic lights and dim up the spotlight on her. We used that effect a few times as symbol for their dreams, of being in the spotlight.

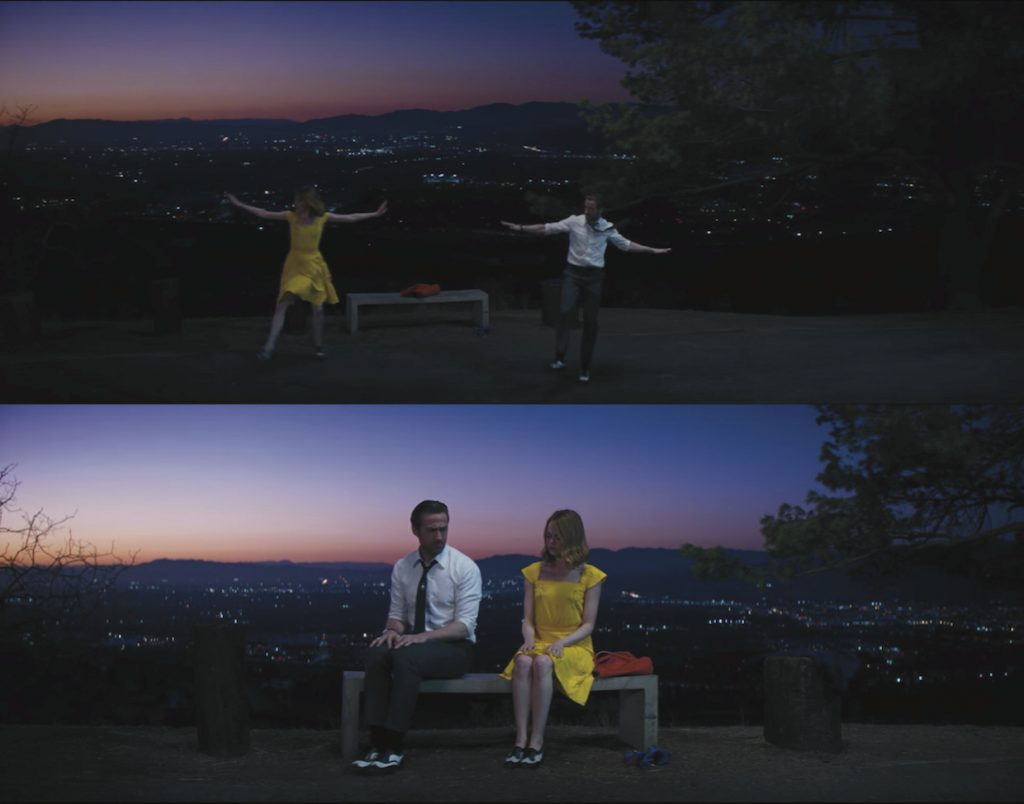

The Scene: Stone and Gosling’s initially contentious relationship begins to soften during a twilight stroll up Mulholland Drive, during which conversation turns to song and then to dance. Sandgren and company shot this extended oner over the course of two nights – getting only five takes each night because the window of perfect light was so short.

Sandgren: We were thinking that we’d find this location more up in Beverly Hills or the Hollywood Hills, but it was impossible to find anything in those places like this spot on Mulholland Drive. This part of the road doesn’t have any lights so at night it’s just pitch black. We parked all those cars, put up street lights, and then lit the scene with film lights. We basically made it like a stage.

On the first day we rehearsed the whole day from 7am to 7pm — first with stand-in dancers and then with [Gosling and Stone] — and we never got the shot perfectly right in the rehearsals during the daylight. There was always something wrong — the dance was perfect but the crane move didn’t work or [vice versa]. It was always something. We only had twenty minutes each night between 7:20pm and 7:40pm when we had the light we wanted. That’s the only time we shot that entire first day, but that scene gave us eight minutes of the movie, which is more than normal for any film.

Filmmaker: Did you always plan to go back and shoot a second consecutive night? I guess you wouldn’t have had dailies quickly enough to see if you nailed it on the first night.

Sandgren: Actually we always saw dailies the next morning. We developed overnight and the film was scanned in the morning and we saw stills from the dailies at like 8 or 9 a.m. But the plan was always to shoot a second day.

Filmmaker: Is the camera crane on a dolly for the move?

Sandgren: In this shot the crane didn’t move (because it had a telescopic arm long enough to cover the scene). There were 27 marks on the crane for the operator to hit — and then the actors had to hit their marks too or the crane marks would be off. The crane operator, Bogdan Iofciulescu, actually does both the retraction and expansion of the arm and the booming himself. Normally there’s one operator for the crane and one operator for the retraction and extension of the arm, but he does it all by himself and he does it by eye as well. He has his marks, but he watches the dancers too. He was so frustrated to get this shot right and we were frustrated too, but eventually we nailed it and when we nailed it we all said, “Let’s remember this feeling because this entire shoot is going to be like this. Every day we are going to feel like we are facing an impossible challenge, but eventually we’ll nail it.”

There was actually only one scene that we couldn’t nail. It was in that green apartment when [Gosling and Stone] sing “City of Stars” at his piano. We were going to do that on a little mini Technocrane and we rehearsed forever and just couldn’t get it right. But we had that same instinct – “We aren’t nailing it, but eventually we’ll get it.” And then someone said, “Why don’t we just shoot this on Steadicam?” And everyone was like “Yeah, why don’t we shoot this on Steadicam? Why are we in this tiny fucking apartment in Van Nuys with a little crane?” (laughs) Then Ari came in with his Steadicam and nailed it right away.