Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Was at a Point in My Life When I Needed to Take a Risk”: Barry Jenkins on his Debut Feature, Medicine for Melancholy

Medicine for Melancholy

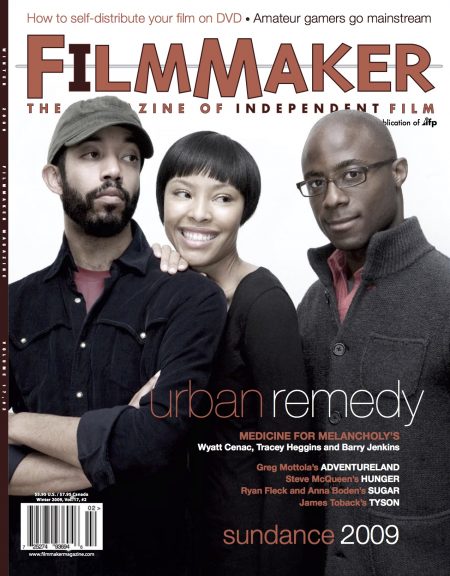

Medicine for Melancholy Nominated for Best Director and Best Picture Academy Awards for his beautiful and incisive Moonlight, Barry Jenkins has long appeared in the pages of Filmmaker. He was a 25 New Face in 2008 and then, just months later, graced our Winter, 2008 cover for his debut feature, Medicine for Melancholy. Online for the first time, here is my interview with Jenkins about the film, an interview that’s a great read and a fascinating look back at the career beginnings of one of our best directors.

Usually lacking the budget to build elaborate sets, independent films have most often been shot on location. Some of our best films — independent or otherwise, actually — have gained a vital texture, a real character and sense of place, from the neighborhoods, city streets or countrysides in which they were lensed.

But something has been happening to our idea of location shooting in the last decade or so. Currency fluctuations, tax credits and investment incentives have lured filmmakers to destinations far from the creative realities of their storylines. Now, it’s common for a filmmaker and his team to journey from state to state as they are convinced that these budgetfriendly locales can easily double for the real places specified in the script. And then there’s what happens when a film is actually shot in the location it’s scripted for. Art departments pretty up locations; extras are professionally recruited background players, not people from the neighborhood; and you can be sure that if there’s a final kiss it will be at night in a postcard-worthy shot angled in front of a beautifully lit bridge or monument. In other words, stories are abstracted from their natural and honest environments.

When I first saw Barry Jenkins’s smart and sensuous debut feature at SXSW, I quickly wrote this on the Filmmaker blog: “Medicine for Melancholy is an appealingly modest film with two strong lead performances and a beautiful sense of balance; it never presupposes that the romantic possibilities of its two illicit lovers are more important than the social reality Jenkins quite deftly embeds them in.” Now, months later and after another viewing, I think my immediate reaction still sums up what I love best about this wonderfully executed film. In addition to humor, relationship drama and romantic mystery, the movie is uncommonly attuned to the social dynamics of its setting. At 7 percent, San Francisco has one of the lowest percentages of African Americans for a major U.S. city, and its preeminent black neighborhood, the Fillmore district, was largely bulldozed in the ’60s in a controversial and ultimately unsuccessful attempt at “urban renewal.” Mindful of this history, Medicine for Melancholy tells the story of Micah, an aquarium installer living in a tiny Mission District flat, and Joanne, who lives in the upscale apartment of her white artcurator boyfriend. We meet them the morning after their drunken one-night stand and watch as they spend a day getting to know each other as well as their hometown through the new eyes of a relative stranger. He’s sardonic, somewhat bitter and pointedly critical of the gentrification and racial divides he sees in a city he half loves. She’s glamorous but remote, and her just-below-the-surface anger is one of the great riddles the film tugs away at.

Stunningly shot by James Laxton in desaturated hues, Medicine for Melancholy is a great relationship film, and it’s a great example of how the simplest of actions — paying attention to the people and places around you — can pay off for a first-time filmmaker. After success on the festival circuit, including the Audience Award at the San Francisco Film Festival, Medicine for Melancholy was acquired by IFC Films, who will release the movie in February. I spoke to Jenkins, one of our ‘08 25 New Faces, in New York City the day after I moderated a panel with him and the four other Gotham Award Breakthrough Director nominees.

Filmmaker: So You and I were both on a panel yesterday with all the Gotham Award Breakthrough Director nominees, and you sat next to Lance Hammer, who directed Ballast. He famously turned down his IFC Films offer in order to self-distribute his film. You accepted yours. Was there ever a moment during the process of making your film when you thought about releasing it yourself?

Jenkins: I definitely considered it. But I think the more productive thing for me to do is work on generating more material, because my passion is as a filmmaker, not really as a film seller. Long before I saw Ballast I heard Lance speak about the process of making the film, and I could tell that it was something he was really intimately tied to. And so of course he would want to control how it goes out in the world. I think my film is very different. It was done so quickly that it’s almost like I didn’t have the opportunity to really develop the sort of relationship that Lance has to his movie. We’re often like, “That movie is his baby.” Medicine, it’s not my baby. It’s our film.

Filmmaker: Tell me about your path to becoming a filmmaker. Before making this film you worked for a director, right?

Jenkins: Yes, I was a director’s assistant on the movie Their Eyes Were Watching God, directed by Darnell Martin, who’s a local New York City filmmaker.

Filmmaker: She’s got Cadillac Records out now.

Jenkins: Right. I worked with her for about nine months right out of film school, and she was great. I learned so much from her. I graduated Dec. 14, I was in L.A. Dec. 20, and I was Darnell’s assistant by New Year’s. It was a very intense, hands-on process — all the way from prepro through postproduction. It was good to see a movie made like that because I think it really helped me make Medicine with completely opposite means. Anyway, I had worked for Darnell for a year and then I worked in development for a year at Harpo Films, Oprah Winfrey’s film company in L.A. And I really just got completely burned out on filmmaking. I pretty much decided I was done. I did something terrible that you should never do: I cashed out my 401(k) from Harpo. The benefits at that company are great, and I used that money to just bum around the country. I gave my car to charity and I gave all my furniture away to my friends. I packed a suitcase and took trains around the country for about eight months. I went to Chicago and New York City, went back home to Florida, went to D.C. and Colorado — the things I felt I should have done when I graduated film school. And it was a great experience, man. I think a lot of the energy that’s in Medicine [came from the] experiences I accrued by stepping away from life in L.A. and just getting to know myself as a person. Then I met a woman in San Francisco, and I moved back there. When that relationship ended, it was kind of a gut check because people would ask me what I did. I’d say, “I’m a filmmaker.” And then they’d go, “What have you done?” I’d be like, “Oh, four years ago I made these short films in film school.” And so I decided I had to make a film.

Filmmaker: You talked on the panel about being inspired by Claire Denis’s film Vendredi soir. Was that the spark of inspiration for Medicine’s story?

Jenkins: The specific story was definitely influenced by Vendredi soir. I love Claire Denis. She’s my favorite director. I saw the movie five years before I decided to write Medicine for Melancholy. When I decided I was going to make a film, I knew it had to be something cheap, and I thought, “What’s cheaper than making a movie with two people?” And so I went back to this idea that was inspired by Vendredi soir: a film that has as its starting point a one-night stand. I was in San Francisco and there was just all this shit swirling around in my head about the city. I felt like I needed to make a movie that was personal to me and that was personal to my experience of the city, and that was when everything sort of came together. I think without San Francisco as a backdrop I would not have made this film. I feel like the issues that the characters are dealing with, particularly Micah, are directly related to the city of San Francisco. And I think the reason why people can really get into the film is because it’s so specific about reflecting the social reality of the time and the place of the city. That’s people’s way in, you know, to this black guy who is ranting about these things. They feel the city weighing in on him, and that’s what makes the movie spin.

Filmmaker: Did you look at other two-people [films], like Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise and Before Sunset?

Jenkins: I purposely did not [rewatch them]. I love them both, particularly the second film. But when it was time to write this film, I almost had a paranoia. I was like, “I can’t make the black Before Sunrise!” And I purposely did not look at any of the so-called mumblecore films before we made the movie either. My connection to mumblecore was that a buddy of mine, Chris Wells, went off and made LOL with Joe Swanberg. And that was the other inspiration for making the film. Through Chris I found out that this guy, Joe Swanberg, was making all these movies for no money, with just his friends, and then they were playing at film festivals and being released on DVD. I was like, “Holy shit, you can do that? Okay, well I’m going to do that.” But then again, I’m always paranoid that I’m going to steal things from people so I purposely decided not to watch any of Joe’s or Aaron Katz’s movies until I had made my film.

Filmmaker: There was another filmmaker on the panel yesterday who talked about how he resisted any semblance of a traditional filmmaking structure when he made his film. I think he said he shot it episodically over a period of years. But it sounds like you embraced the structure of a professional shoot even as you shrunk the size of it.

Jenkins: Yeah, that was definitely the idea. I mean, because me and all the people who worked on the film all went to Florida State University film school together, we were trained to make movies that way. There’s a protocol, there’s an a.d., and there’s a script sup’ — all these elements that are designed to make the film come in on time. I mean, that’s basically all it boils down to. There are too many people on a Hollywood set because they want to guarantee that the movie comes in on time. We really wanted to get the film done as well — we only had 15 days to shoot it, so we had to be organized. And [even though we shot on tape] we brought the rigor of not being able to run the shot for 40 minutes. Just set up the take, decide what we actually need in this moment, get it, and move on. That was very important because we wanted to cut the film in a month to get it into South by Southwest, and we could not have done that if we had had a lot of improvisation or if we had had a ton of footage. We only had one guy cutting the film with no editing assistant so it was really important to do things the way we were trained to do them, which was on film. It was also important to us that there be a certain formalism to the film’s aesthetics, a film language. It was as important as saying something about the city and about the characters.

Filmmaker: How big and who was on your crew?

Jenkins: It was myself, James Laxton, our cinematographer, who was nominated for an Independent Spirit Award for cinematography; the sound guy, Nikolas Zasimczuk, a local San Francisco guy; and then our buddy Alejandro Cruz, who went to film school with us. He was the gaffer-slash-key grip-slash-camera assistant. Cherie [Saulter] and Justin [Barber] were our producers, and they’d come by and swap out P2 cards or hard drives, or bring us food. And that was about it, man.

Filmmaker: So no art department?

Jenkins: No, I was the art department. I was the costume department. [laughs] I was the script sup’. I was the a.d. [laughs]. Yeah. But I mean it’s two characters who only have one wardrobe change, so we kind of reduced the risk. All the locations were real locations so I didn’t really have to production design many things.

Filmmaker: Did you have a production office and people working behind the scenes?

Jenkins: No.

Filmmaker: Nobody clearing the locations?

Jenkins: It was just Justin and Cherie running around clearing the locations. [laughs] And our editor, Nat Sanders, was in an office cutting the footage. We would shoot the first day, give it to him, and he would be editing the first day while we were shooting the second day. That was it, man. That was the little setup.

Filmmaker: Were there crew people that you wish you had that you didn’t have?

Jenkins: You know, in the process of making the film, no. I mean, there are certain scenarios where I think James could’ve used two or three people. He could’ve used a few more lights also. He did a great job with what he had, but it would’ve been nice to have had a real grip, electric and camera package, but without the 40 people that comes with that. Really the only thing that I think we missed was a casting director during the preproduction. I think that’s essential, and we didn’t have one of those.

Filmmaker: How did you find the cast?

Jenkins: By luck. There’s this thing called NowCasting.com, which is sort of the Craigslist equivalent for actors. That’s how we found Tracey Heggins, who plays the lead. She’s been in other very small things. I think she had done some television stuff, but her background was in print modeling. She auditioned, and that’s how we found her. And then Wyatt [Cenac] was doing stand-up in L.A., and we kind of just stumbled onto him. A friend of a friend knew him and sent us a clip of him doing this thing on YouTube, and we thought he was really interesting. We called him in, he read and he was perfect. It’s weird. He definitely wasn’t the character as I had written him, but he was so unique and specific that I just knew this guy could play this role, and we’d tailor the character to his strengths, which made the movie a bit more comedic than it was in script form.

Filmmaker: How did actually shooting the film in San Francisco affect the movie?

Jenkins: All the dialogue [about the city] is in the script. But Tracey’s apartment — or Jo’s boyfriend’s apartment, the place with no art on the walls — that was a location I got as a house-sitting gig while we were shooting the film. Wyatt and I were going to live there, and when we got there, I walked in and I was like, “Oh man, this is perfect for her place.” And so we put it into the film. It’s in the Marina, which is the tony, whitewashed part of town, so it’s a perfect contrast to where [Wyatt’s character] lives. Later in the film, there’s a moment where Wyatt is moving his bike around the apartment when they’re about to go out and he makes a joke, which is completely ad-libbed: “You should get yourself a fixed-gear bike, you’d be like Mae Jemison: The first black woman to ride a fixed-gear bike in the Marina. Hell, you’re probably the first black woman in the Marina.” And right there, only because we got this location by housesitting in the Marina, we had this great line that perfectly cuts to the core of the issues between these two characters. It’s a real place in the city, and Wyatt made a real observation about its location. Things like that, to me, are the best moments in the film, when San Francisco is directly reflected in the lives of these fictional characters.

Filmmaker: I love that line that Karina Longworth wrote on her blog about the cinematography of the film. She said that like the city, it was 93 percent desaturated.

Jenkins: When Karina wrote that, it was the first time that I was aware of that, I would say, coincidence. But yeah, if you go through our digital files, the movie is 93 percent desaturated. That’s a testament to James Laxton, our cinematographer. James and I had decided that we were going to desaturate this movie to reflect the mood that I felt was appropriate for these characters and the tone I wanted to present of the city. And so we went shot by shot and did it ourselves. James was born and raised in San Francisco, and he’s seen the [gentrification] process that the character Micah is talking about.

Filmmaker: Did he have to sell you on that? Because it’s a bold decision — it’s nearly a black-andwhite film.

Jenkins: He did not. We made two short films in film school, and one of them is even more audacious in the color correction than Medicine for Melancholy. That movie is basically green. No, James and I are always very, very much in line on decisions like that. We sat down to do the color correction and went shot by shot with no audio. We did it just like: If you had to watch this film with no sound, you couldn’t hear a word, could you get the mood of the film? That was the inspiration for doing the color correction.

Filmmaker: Did you work with the actors much before shooting? And, one thing in particular: Tracey’s character comes into the movie with a sense of deep anger. Was that anger on the page, or did she bring it to the character?

Jenkins: [laughs] It was sort of in the script. There’s an internal life that’s going on in the character of Jo’ in the film. I got to speak with Tracey [before shooting] a lot more than I got to speak with Wyatt. Wyatt came on very late in the process — much later than Tracey did. We only had time to do one read-through [with both actors] in L.A., and we decided that that would work because we had these two characters that don’t really know one another and we knew we were going to shoot the film in sequence. We didn’t have any rehearsal. But because I knew that within the script her character is very withheld, I actually wrote this huge packet for Tracey. Wyatt gets to say all these things, so I wrote for Tracey this eight-page, single-spaced packet that [told] the life of her character right up until the [beginning] moments of the film. And one of the first notes I gave Tracey was that all those things in that packet are swirling around in this character when we meet her. All that information, all that history is coming to the surface right now, but it’s not verbalized. And I think for the most part she really found a way to get those things across, one of which was that sort of misdirected anger. As the film goes on she figures out where it should be channeled.

Filmmaker: Was her character inspired by a specific person?

Jenkins: I mean the movie, it’s not autobiographical, but it is about myself and a couple of women in my past. [Her character] was kind of taken from maybe my perception of the real-life experience of these women’s relation to me. And I think Tracey does a really wonderful job of sort of getting inside my head. Again, I think it was very good for Tracey to be able to talk to me about the character and figure out where I was coming from.

Filmmaker: It’s funny, Tracey’s character seems to represent the “relationship” thematics of the film while Wyatt’s character is a lot of the politics.

Jenkins: And he needs to shut the hell up! [laughs]

Filmmaker: Were those your thoughts? His ideas?

Jenkins: Those are things I’ve said. But you know, I was showing the movie at CalArts for film students, I was very candid in talking to them, and I said, “There’s a scene in the movie that shouldn’t be in the movie. As a filmmaker who I feel is a better filmmaker for having made this film, if I made it again there’s a scene that wouldn’t be in the film.” What scene is that? It’s the very last scene, when the characters are walking and talking in the street, and they have the big verbal fight. It’s a bit redundant, and I think it’s a little bombastic. It’s me speaking and not necessarily the characters. And I think, as a better filmmaker, I wouldn’t put in there. But I think as a human being needing to work out those emotions, it had to be in the film. That’s one of the things I’ve learned about the life of a movie: how my relationship to the film is going to change over time. Already, just in the span of six months, I realized there’s something I did in this film that as a filmmaker I should not have done, but as a person I had to do.

Filmmaker: So you feel that this film, perhaps, represents a culmination of a certain point in your life?

Jenkins: It definitely represents a huge turning point in my life. I just turned 29 years old a week ago, and this is by far, I think, the most important thing I’ve done. And it has nothing to do with the reception or the quality of the film, but just about deciding to make the film. It was a very big decision.

I showed the movie to this very small high school in Oakland, a charter school with only about 50 students in this inner-city neighborhood. These weren’t film students. I think the teacher just thought it would be good for them to see a young African-American male who’s done something quasi-positive. I was talking about the movie, and [one student asked], “So did you make any money off the movie?” “No, I did nothing but lose money. I’m in debt because of this movie.” And this 12-year-old girl goes, “Wow! That’s a really big risk.” It’s funny, I never really think of things in such simple terms. And then I was like, “Well, yeah, I guess it was.” I guess I was at a point in my life when I needed to take a risk — on myself and on my friends. But now I’m beyond that. Now it’s time to move on to the next challenge, which is: Who am I as a filmmaker? What kind of movies do I want to make? What kind of movies am I going to make? And again, that’s another reason why I kind of want to just step away from Medicine, why I don’t want to go out on the road and really try to pound it. I think this movie — or my relation to it — is done.