Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance Announces Groundbreaking Transparency Project at #ArtistServices Workshop

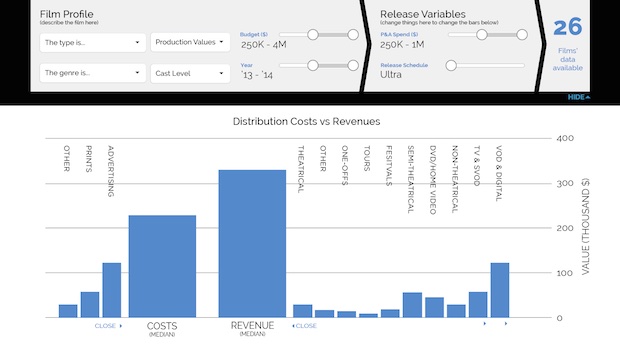

A detail from the Transparency Project analytics tool

A detail from the Transparency Project analytics tool Data — it’s the most coveted property in independent film. While studios base their greenlight decisions on finely-honed models derived from the financial performance of numerous other pictures, many independent filmmakers perilously based investor pitches and distribution decisions on anecdotes and hearsay. What used to be simple extrapolation (“If that film grossed X, it probably did Y on home video”) has become a near impossible exercise in the age of digital distribution, in which paltry box-office returns hide “the real numbers” — a dizzying matrix of VOD stats, download figures, Netflix license fees and more and more obscure sub-categories of revenue.

For independent producers, this opacity is a growing problem, preventing them from securing the private investment needed to make movies. Says producer Rebecca Green, whose It Follows is playing in the Midnight section of the Sundance Film Festival, “From a producing standpoint, [knowledge of financial data] is an essential tool in raising money. When we put together our business proposals, we are basing our raise on ‘comp’ films. What we have now is only box office, but box office is not an accurate measure of independent film. If we have VOD numbers, we can make a better case to our investors and possibly raise better money.”

“Independent film models of distribution have changed in the last decade, and even the last year,” concurs Cinereach Producer in Residence Paul Mezey. “The measurement systems that films’ performances are understood by are antiquated. Given that filmmakers today are coming up with hybrid and non-traditional avenues using new technologies, we need to have more information about how revenue is being returned.”

This lack of information is impeding filmmakers from thinking creatively about their releases, agrees Chris Horton, Director Creative Distribution, Sundance #ArtistServices. “There is such a range of distribution and windowing strategies filmmakers are faced with today,” he says. “Too many films try a ‘one size fits all’ traditional strategy.”

Enter the Transparency Project,announced today at the fifth annual #ArtistsServices Workshop at the Sundance Film Festival. Founded in partnership with Cinereach, and in collaboration with a group of other non-profit organizations, the Transparency Project is a groundbreaking initiative that will allow aggregated film financial data to be shared among producers and filmmakers using an online analytics tool. This tool, when it is fully developed, will allow those comparisons Green spoke of to be easily calculated.

The Transparency Project website is now live, offering a sneak peak of the analytics tool and a call to filmmakers to participate by submitting their data. As the Project builds out, that data will be anonymized and aggregated into various categories, including budget, genre, cast level, production quality, P&A spend and windowing style. A beta version of the tool will launch this Spring, open to filmmakers who have volunteered their data, and it will allow, states Sundance, “individuals to manipulate the data set in real time by selecting various film criteria (genre, production level, etc.) and release variables such as P&A spend or windowing strategy.”

Currently, 95 films have supplied data to the Project, all features budgeted under $7 million and released from 2012 onward with at least one full quarter of digital reporting. Two hundred additional films have pledged to submit their data in the weeks ahead.

In the past months, Filmmaker has spoken to the team behind Transparency Project — Horton; consultant Brian Newman, of Sub-Genre; Sundance Institute Executive Director Keri Putnam; Cinereach Executive Director Phillip Engelhorn; and Mezey — to understand the Project’s goals, its potential and the work undertaken to arrive at today’s public announcement.

For Putnam, the Transparency Project is a natural outgrowth of the organization’s overall mission. “Sundance has had a long history of empowering storytellers to find their creative voice and to give them the space to develop their work,” she says. “On the creative side, that includes the Labs, grants, and the platform of the film festival. Now, at this time when so much has changed in the way we distribute, make and market our films, filmmakers need organizations like ours to help them tactically and strategically.”

“Not every film that plays our festival walks away with ‘shut up money,’” adds Horton. “There are 200 feature films coming through the festival, and the vast majority are not walking away from the festival financially in the black. And then after the festival, these filmmakers don’t really know what their films are making in outlets other than theatrical box office. We needed to fix that.”

Mezey says the Transparency Project’s online tool will offer producers sophisticated means to imagine the future life of their films. “The goal is to create a tool that allows you to model out different scenarios, to compare what has happened over a certain time period to films that look similar to your film. Where are the revenue streams coming from? What costs does it take to get those revenues? How valuable is a theatrical release, and what is the tipping point in terms of overspending on theatrical? How does box office correlate to VOD or other online digital distribution?

“You’ll be able to unpack a number of variables and model out different scenarios around different budget levels and P&A spends,” he continues. “If you go to Sundance and a distributor wants to do VOD with a small theatrical for your film, you’ll understand why that might be a better model because you’ll have the numbers. You’ll see that [a larger] theatrical could cost four times as much.”

Or, as a Transparency Project white paper being published today states more simply, “… film data is new to the field, and that data, like a film, must tell a story. Our goal with The Transparency Project is to work with the field to collect, analyze and present data in a manner that helps us tell the story of the challenges and successes of independent film in the marketplace.”

The Transparency Project is launching with a number of non-profit partners, who will encourage their filmmaker members to contribute their data. As of today, these organizations include Arthouse Convergence, Austin Film Society, Britdoc, IDA, IFP| ITVS, IFP Festival Forum, The Film Collaborative, FIND, POV, San Francisco Film Society, Tribeca Film Institute, the WGA East and the Film Society of Lincoln Center. “What excites me the most is potential collective impact of non-profit organizations in this time of great change,” Putnam says. “I don’t think we’ve begun to explore the ways we can together have an impact.”

Cinereach Executive Director Phillip Engelhorn explains his organization’s role in the project: “The core around what this project is trying to address — bringing transparency around hard-to-get data — has been talked about at Cinereach for a while. Sundance was interested in this subject too, so we joined them to see if we could actually do something about this problem. We’re supporting Sundance financially, and Paul has been incredibly involved with Brian, Keri and the whole Artist Services team. We have regular conference calls, discussion potential partners, set timelines and goals.”

Says IFP Executive Director Joana Vicente, who will be urging her members to contribute their data to the project, “The IFP is proud to be a supporting organization of the Transparency Project. We think it is vital that this information is gathered and shared. The Transparency Project will ultimately empower filmmakers by giving them the tools to learn from others and create realistic business models for their projects.”

The Transparency Project had its birth in internal discussions at Sundance back in September, 2013, with the first roundtable discussion that included filmmakers taking place at the #ArtistServices workshop at the 2014 Sundance Film Festival. It was around then, says Horton, “that we realized that this was something serious, something major. We needed outside help and manpower, which is when we brought Brian Newman on board.

Newman, whose Sub-Genre has consulted on new business and distribution models for films like DamNation, has been leading the reach-out to filmmakers. That communication initially took the form of a survey, an activity that led, says Horton, to “core insight [around] how we are collecting data, what kind of data is important, and whether or not to keep projects anonymous, which we are.”

A more formal presentation to producers was made at the Sundance Producers Conference in August, and the resulting feedback guided work on the project this past Fall. Preliminary data was shared at the Conference, as was a mock-up of the online tool the team was building. Says Newman, “We explained basic statistical terms, like the median versus the average, and we learned that filmmakers don’t think about data everyday.” “We learned that we were collecting almost too much data,” says Horton. “The original iterations of the survey were pages long. We’ve pared that down now. As Nate Silver likes to say, we’re looking for the signal in the noise.”

“We had to slow down and make sure the tools are user friendly,” continues Newman, “The prototype we built back in August tried ‘the kitchen sink approach.’ We had so many options, you’d select something so specific you’d have no data! So, we learned that we had to simplify everything.” That simplification has involved collapsing the multiple distribution strategies used today into three of four categories. “For example,” says Newman, “there are multiple ways you can window a movie now, and we are grouping some of them together.”

How specifically will types of films be able to compared? Will a mumblecore office comedy be able to be compared against a neo-realist-style coming-of-age tale? “Probably not in the early stages,” responds Newman. “You might want to look at the difference between a rock music doc and a social issue doc, but you don’t need to be more nuanced than that.”

What about the effect of good — or bad — reviews on a film’s financial performance? “We are not looking at critical reception as part of our criteria, but we could easily expand into that later,” says Newman. “When we unveil the tool it’s not going to be final or gospel,” adds Horton. “We’re all about input from the field.”

Underlying the entire Project is the idea of anonymity. Because the data will all be aggregated, no user, whether they be filmmaker or distributor, will be able to deduce the budget or revenues of a specific film. “As of now it is about aggregate data and hypothetical film modeling,” explains Newman. “We do plan to allow you as a producer to eventually log in to your titles and look at them versus the data set, but we don’t envision looking at someone else’s data. I imagine that within this year you could both model a hypothetical film and also look at your real data versus the aggregated data.”

Franklin, founder of the filmmaker web platform Assemble and Creative Director at BritDoc, is heading the development and design team building the Transparency Project’s online tool with Jeb Coleman of ProductionSense. An initial version of the prototype was developed by the Harmony Institute, and Franklin says his goal has been to make it simple and user friendly. “Early versions of the [platform] had huge amounts of working parts and data,” he says. “My job is to advocate for the user, to make what is a hard process as easy as possible to use. In an ideal world, we’d have just one button. You’d press that and get what you want. That’s not possible, but we are asking ourselves, what’s the minimum input you can give the system to get the maximum results? My role here is to make this a joy to use.”

In order to reach today’s #Artists Services presentation and website launch, the Transparency Project has faced numerous challenges. As Newman mentions above, filmmakers aren’t used to thinking granularly about data, and the success of the Project will depend on its ability to help filmmakers distinguish between subtly different distribution forms. Says Franklin, “We need a shared glossary for the industry about what all these terms actually mean. For example, what do you call all the different VOD items? It iTunes ‘iVOD’ or ‘DST’? There are all these different ways of describing different types of VOD, and they all overlap in different ways. We get away with it today, but once you’re presenting this information as data, you need to be specific.”

The biggest challenge, however, has wound up being the most obvious: obtaining data. Filmmakers may say that sharing data is a good thing, but try getting it from them. Between February and December 2014, the Project has reached out to 300 filmmakers, a mix of documentary versus narrative, budget levels, production-quality and cast levels. Remarks Newman about his polite cajoling of filmmakers, “The largest number of filmmakers we are waiting on are the ones who have already said, ‘yes.’ And then it’s more than a month of emailing them gentle reminders. It’s like asking someone to dig up their tax forms and reenter them in a computer form a second time — it’s not fun or easy. Getting the data sent to us has taken much longer than we ever imagined.”

Surprisingly, Newman says the data laggards are precisely the ones you’d expect to be the fastest: self-distributing microbudget filmmakers. “If you are a filmmaker who does self or direct distribution and have divided your rights, you are not looking at one report,” he explains. “Sometimes the slowest to respond are ones have been most inventive. Those filmmakers that went with a traditional aggregator or distributor — well, a lot of them report on a regular schedule and you can send along a PDF.”

“I’m impressed with how much data we have so far,” says Horton, “but it’s amazing how many films we have reached out to who have said, ‘We’ll get to it when we can.’ Some are too busy, some of them have an NDAs with their distributor.”

That brings up another challenge of the Project: securing the participation of distributors, whose buy-in will be important to its long-term success. From conversations with the Transparency Project team, industry outreach might best be described as a gentle back and forth. “We’re not going to [distributors] and saying, ‘Give us the data!’” says Horton. “We are saying, ’This is happening, and how can it benefit you? The world is heading towards this — emerging, self-distribution outlets are giving filmmakers access to real-time data. Don’t see it as a threat.”

Says Newman, “Some distributors are sharing, and some are not. But we’re not going out to everyone and their son. We’re going out to distributors who would seem like allies and assuring them that this is being done in a fair, anonymized manner. A few of these distributors are seeing the value in being able to look at the field as a whole. A significant number of them are not opposed to reporting things in a better manner, and they are starting to share their data.”

Says Mezey, “We have been moving incrementally, trying to build critical momentum. Most of the data [currently used by the Project] has been out there in some way. We’re not trying to expose the business model of any specific distributor. We are not looking at deal structures of Sony or Radius; we are looking at point-of-sale transactions. In fact, one distributor’s output deal is less relevant because it becomes a specific situation. If information like that is pulled into system, it washes out. I don’t think [the Project] is a threat to distributors.”

Another challenge: surmounting the tech-crowd assumption that data is meant to be proprietary, that it exists to be scavenged, hoarded, algorithmitized and monetized by the next Google or Facebook — not disseminated by a nonprofit organization.

Replies Putnam, “I don’t view the Transparency Project as oppositional to businesses — I see it as additive for everybody. I think people will see that with the way we have structured the project we are not jeopardizing proprietary data but instead are adding value. That’s not to take anything away from data-driven business, but I believe that more transparent data is good for the industry overall. Broader access to data is only going to make better ideas emerge. Some of them will be business ideas, and that’s fantastic, and some of them will lead to profits for individual filmmakers.”

As part of today’s announcement, Sundance has listed a number of for-profit distributors who “have expressed their support of the Transparency Project mission and its ideals.” These companies, who are expected to participate in the future once they are comfortable with the Project’s implementation, include, among others, Radius, Oscilloscope, Cinedigm, Vimeo and Cinetic. “The Project will continually add collaborators from across the industry and incorporate input from the field,” Sundance says in a statement.

A final challenge is, perhaps, a paradoxical one, one not concerning methodology or implementation but the goal of the project overall. Independent film fundraising has always relied to some extent on dreams — the investor who imagines he or she will back that one film that scores a giant deal at Sundance and then heads to the Oscars. And, indeed, this dream can be perpetuated by our industry itself. Says Mezey, “Often the only [financial data available to filmmakers] are the case studies, and those are usually the success stories.” When wining and dining an investor, would a producer rather cite the sales figures of Beasts of the Southern Wild or Fruitvale Station or an obscure picture that took years to eke out a profit on multiple online platforms? With filmmakers often soliciting funds from first-time investors, doesn’t fundraising depend to some degree not on financial transparency but instead the lack of it?

Parts and Labor producer Jay Van Hoy, who participated in the early roundtable discussions about the Project at the Sundance Institute, and who is here at Sundance with The Witch, pushes back on this notion. “As a producer, I don’t know that I benefit at all from not being transparent with my financing partners,” he replies. “I really feel it is important that producers and filmmakers understand how films are working in the marketplace and not have exaggerated notions. Oftentimes films are unstable in production and that instability comes from people projecting their fantasies or having outsized expectations. It’s the same thing when dealing with distributors. The last thing distributors want to do is talk to financiers or producers who have crazy fantasies about how their film is going to perform.

“I don’t understand how it hurts us for information to be out there,” Van Hoy continues. “I think it’s important we be honest with each other and ourselves. My primary goal in talking with investors is making them understand the risk they are taking. Ultimately, if they are taking too big a risk, they are going to realize it at some point, and we’re still going to be together — on set, watching the rough cut, or at a film festival. I don’t want to take advantage of someone else’s inexperience. That’s not the business I’m in.”

What if, when all the data is aggregated, a more worrisome conclusion is formed: that the independent sector as a whole isn’t working, that far more money flows into it than is returned through all the various revenue streams? Counters Mezey, “There is a robust economy of film that is working. It’s not as if there is no marketplace. There is a demand, otherwise Sundance wouldn’t exist. No buyers would go. The problem is, as distribution systems change, everyone is working in the dark and not creating new formulas for success.”

“If [independent film distribution revenues] are that bleak, let it out,” says Van Hoy. “Let’s all know how bleak it is. It’s better to find out sooner than later. And if things do look bleak, the deal structures need to change. All of our deal structures are based on 15 or 20-year-old precedents. It was a completely different marketplace then.”

Indeed, to talk with the entire team behind the Transparency Project and the individual producers who have provided their input to its development, the feeling is not one of trepidation over what numbers the data may deliver but an optimism over the possibilities the sharing of that data will create, whether they be clearer reporting models or new forms of distribution itself. “My hope is that if we’re successful at doing what we are setting out to do, we will be creating a living tool for distribution plans, something that’s broadly useful for all sectors of the industry,” says Putnam.

Says Engelhorn, “In the same way that Sundance is fomenting amazing things with #ArtistServices, I’m hoping this project will open doors to other non profits. We are charging ahead, but we want others to join. We are trying to do something beneficial; we are not competitive.”

“We are creating a way to empower people with info according to their own values,” concludes Mezey. “We love art, film and affecting people, and we want this business to be viable. There won’t be private investors and distributors if no one makes content. In order to overcome fear and distrust, we have to show that this [Project] can work and be valuable to everyone. By being nonprofits, we are uniquely positioned because we are not trying to make money. At the end of the day, this Project needs to happen — we need to create sustainable systems.”