Back to selection

Back to selection

Notes on Real Life

Adventures in Non-Fiction Storytelling. by Penny Lane

Notes on Under the Gun (Or, When is Fiction a Crime?)

Under the Gun

Under the Gun A work of art teaches you how to look at it. It builds its own user guide.

In nonfiction, the user guide includes such FAQs as: how should one interpret this work of art’s relationship to reality? What type of trust should a viewer grant or deny it? And how does this film conceive of truth and beauty, which are sometimes but not always the same thing?

Some documentaries come with confusing manuals. Some are purposely confusing; others are just confused. These films are “problematic” in the way they subvert expectations about the terms of the documentary promise. They push buttons, and in doing so can earn themselves awards, or, as sometimes happens, lawsuits.

The makers of Under the Gun, including executive producer Katie Couric, found themselves in the latter category when the Virginia Citizens Defense League (VCDL), a gun rights organization whose members appear in the documentary, sued for defamation. At issue is one scene — or one edit, really.

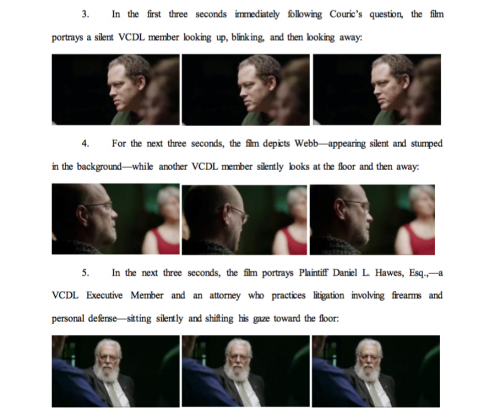

In the scene, Couric asks the VCDL members a simple question about background checks. They are then shown in awkward silence for eight seconds, providing no answer.

In real life, they provided at least six minutes’ worth of answers (more on that later). At worst, this edit is deceptive and unethical. At best, it’s appallingly incompetent filmmaking.

But at what point does a bad artistic choice become a crime?

The VCDL’s complaint is a fascinating text, a 50-page work of film analysis complete with illustrative still frames. (See bottom photo; I only wish I wrote about film with this level of rigor.) It breaks down, in excruciating detail, this eight-second exchange in order to prove it is a “work of fiction.” The word “fiction” is used over and over. The attorneys could have just said Couric and her team lied, but I think they knew that calling a documentary “fiction” packs a better rhetorical punch; it really hits us documentary makers where it hurts.

But, even so, making fiction is not a crime. Nor is lying, or being a jerk. What is a crime (or, more precisely, not a “crime” but a civil wrong) is defamation. In the United States, defamation law varies from state to state, but in general a defamatory statement: 1) purports to be a matter of fact — not opinion, and certainly not fiction; 2) is false — not just innocently false, but false in a way that shows actual malice or reckless disregard for the truth; 3) causes reputational and/or professional harm to the defamed person.

Embedded in the VCDL complaint is the assumption that a reasonable viewer would interpret the contested scene as a true representation of what happened in that interview. (I can’t see how it could be conceived as defamatory unless it clearly purported to be a true statement — a matter of fact.) But these eight seconds didn’t happen in a void; they happened somewhere inside a nearly two-hour film. Was the edit constructed to be read as literally true?

I figure the only way to judge how a reasonable viewer would answer that question would be to learn for myself how the film teaches you to watch it. So I watched it.

Under the Gun opens in a dramatically lit room, maybe a classroom or some other institutional space. There are a series of tight, nervous shots of empty chairs. Statistics flash across the screen in white text. Except they’re not exactly statistics — they’re predictions:

Before this film is over…

22 people in America will be shot.

6 of them will die.

By leading with these statistics, Under the Gun immediately answers the first FAQ in its documentary user guide: what kind of documentary is this, or, why was this film made? The opening text implicates me, the viewer: here I am, sitting on my ass watching a movie instead of doing something. And immediately, with those statistics, I know that this film will tell me to do something about this problem. In its opening minutes Under the Gun announces itself as an Issue Film, and, more specifically, an Advocacy Film.

How should I interpret the numbers? Are they accurate? Leaving aside the fact that I have a skeptical relationship to statistics, where do I guess these numbers would fit on a scale of “Totally Made Up” to “Beyond a Shadow of a Doubt True”?

Well, since I’m watching an Advocacy Film, I expect the film’s makers to make a decisive argument about a course of action I should take, and that they will do their level best to marshal facts which are as dramatic as possible to make their point. But I also believe these facts will withstand at least nominal fact-checking.

Why do I believe this? Just thinking this is an Advocacy Film isn’t enough. (I mean, like… Zeitgeist is an Advocacy Film too.) But I know from promotional materials, reviews and the Sundance synopsis that the film’s Executive Producer and narrator is journalist and news anchor Katie Couric.

Although she is not the director, Couric’s name answers the second question in the Under the Gun FAQ: who made this film? And with Couric’s name comes mainstream journalistic credibility. For all I know, she wasn’t all that involved in the film’s production, but she was at least willing to attach her name to it.

So I am not even 30 seconds into the film and I feel I’ve gotten a handle on this film’s user guide. Of course, I could be wrong; but this is, so far, what the film has taught me about how to watch it.

A group of people file in to fill the chairs, now revealed to be arranged in a circle. An offscreen woman’s voice — I guess it’s Couric’s — speaks, not in a formal voiceover from a recording booth but diegetically, from somewhere inside the circle of chairs in that room (we don’t see her face):

“First of all I want to say thank you all so much for doing this. Because we want to get all different points of view. And I know you guys have a specific point of view on this issue. I am going to start with a show of hands, how many of you are carrying guns now?”

Wide shot of all of the hands going up. We see one man’s face, in profile; he seems to smirk as he raises his hand. Couric flatly responds, “All of you,” from her place somewhere inside that circle. (Is she even in that room? I got a glimpse of a blonde woman in the circle, but her face was carefully obscured.)

Then the film begins. Slick archival-and-stats montages, mixed with the grieving parents of Newtown as well as former Congresswoman Gabrielle Gifford, a victim of gun violence. After I spend some incredibly sad moments watching Gifford try to recover her ability to walk and speak, I return to the room with the VCDL. The room feels so much darker now that I’ve been in all the other scenes, which were so brightly lit.

(Photo caption note: The VCDL’s complaint also points out “manipulative lighting techniques.”)

Repetition of the intro: “How many of you are carrying guns right now?” Again, all the hands go up. The gun rights discussion begins.

And then the edit, just over 20 minutes into the film. Couric’s disembodied voice again (this is getting weird, seriously; is she even in that fucking room?!): “If there are no background checks for gun purchasers, how do you prevent felons or terrorists from purchasing a gun?” Eight seconds of profound silence, with the members of the Virginia Citizens Defense League looking uncomfortably into the middle distance, at one another for help and at the floor. In the context of the pace of Under the Gun, these eight seconds are excruciating. The silence is comically long.

It’s clearly constructed as a metaphor — or I believe it was meant to be interpreted that way. Because I do not believe that this extremely simple question could have flummoxed the VCDL this much, it’s hard to believe the film intends for me to think of it as literally true. In this sense, I at least sort of believe the director when she says her intention “was to provide a pause for the viewer to have a moment to consider this important question.”

Yes, this explanation seems absurd, and if that was the goal, it didn’t work — as noted by David Folkenflik at NPR, the fictionalized pause was “rhetorically unnecessary — the director simply could have cut away after Couric asked the question” and created a pause some other way — but I can at least imagine the filmmakers believed they were making something like poetry in the moment of creating that scene. It’s actually a kind of beautiful scene, but, crucially, beautiful in a way that feels not of this film.

Perhaps they had one of those ecstatic truth moments but forgot they weren’t making a Herzog film. Or, if this were a Borat film, I’d know this was just a mean joke. If this were Adam Curtis, every scene would read equally “out of context.” But the film I have been taught to watch is not Herzog, nor Borat, nor Curtis — nor Zeitgeist, for that matter. I, reasonable viewer, have been told it is an Advocacy Film, about an Important Issue, narrated by Katie Couric, who used to anchor The Today Show and the CBS Evening News.

All of this raises the question, what is a reasonable viewer? Is there such a thing? What level of sophistication and attention and experience do we expect of a viewer to be able to interpret the truth claim of a scene like this?

Do I, for example, know too much to be a reasonable viewer? If I hadn’t known about the lawsuit beforehand, would I have believed — perhaps because it pleased me to think so — that the VCDL is this stupid about the issue they’ve devoted their lives to?

I don’t think so, but then again, here is the only mention I could find of this scene in any review of Under the Gun: “A group of blustery members of the Virginia Citizens Defense League, however, suddenly remain painfully quiet when Couric asks them the hard questions.” So maybe it doesn’t stick out stylistically as much as I think it does. (It is true that in Under the Gun there are a few winks to Michael Moore: happy music laid ironically over a sad scene, etc. Perhaps I have just failed to read the whole user’s guide, which does, in a few isolated instances, announce a certain strain of Advocacy Film, one we know not to take seriously except when we want to). Or, possibly, sophisticated viewers really do interpret this scene as a matter of fact — maybe just because they’re not really paying attention.

Maybe those eight seconds only seemed so insanely long because I watched the film so closely. I was certainly aware of my concentrated attention. Indeed, by the end of the opening credits, the film’s user guide had let me know that this was the kind of doc tightly constructed to pull me along without my having to do any heavy lifting. This is perfectly suited to its rhetorical style; it is an effective polemic.

Once the controversy broke, Couric posted a message on the Under the Gun website taking responsibility for the misleading edit. She wrote, “VCDL members have a right for their answers to be shared and so we have posted a transcript of their responses here.” From this transcript, you would think the VCDL lied about having responded for six whole minutes, unless they talked incredibly slowly… with lots of long… awkward… pauses. The whole exchange is less than 300 words.

But get this: it turns out that this transcript is also edited. It truncates (by over 70%, according to the complaint — I did not measure it myself) the answers the VCDL provided about the efficacy of background checks. I know this because VCDL President Philip Van Cleave posted audio of the entire interview with Couric. It seems he made his own recording. (“I do that as a matter of course when I’m doing things like that,” said Van Cleave in an interview. “It has saved me a few times.”)

The edited transcript ends with “WOMAN” (actually Patricia Webb, one of the named plaintiffs in the defamation suit) asking a rhetorical question: “Tell me one law that has ever stopped a crime from happening.” In the unedited version, Couric responds to Webb’s question by bringing up the Brady Bill as an example of such a law. Couric and members of the VCDL then debate — for quite a while — whether the background checks put in place by the Brady Bill led to any decrease in gun-related violence. Perhaps most importantly to me, as I listen to the full exchange again and again in my attempt to grapple with any possibly “true” meaning (true in any sense of capturing the essence of this exchange) of the deceptive edit, there are no awkward silences or pauses.

This marks the point where I lose my patience with the filmmakers and run out of sympathetic excuses. Okay, so the filmmakers made a choice to deny the VCDL its answers in the film. That kind of sucks for the VCDL, but it’s not that big of a deal in and of itself. The construction of the eight-second “pause” was bad and unethical filmmaking, but nobody is perfect and I can sort of see how it might have happened. But after all of this, can anyone tell me what the fuck the point is of issuing an apology which says, “VCDL has a right to their answers,” and then releasing a transcript which omits almost all of their answers?

This essay is not an attempt to judge the merits of the VCDL’s defamation case. That I leave to the courts (duh). That being said, all of the lawyers I spoke to* expressed doubts about whether the VCDL has a good chance of prevailing. In this group was Eugene Volokh**, a UCLA law professor who teaches both free speech law and firearms policy. He was especially doubtful that the VCDL would be able to prove “professional harm.” But Volokh cautioned me, “I don’t want people to come away from [this] thinking that deceptive editing could never be defamatory — it certainly could. There’s nothing new about the proposition that you might defame someone by quoting them out of context.”*** Some fictions are indeed a crime.

Under the Gun failed its viewers, its subjects and itself by building a user guide that malfunctioned. The manual claimed, but did not honor, mainstream journalistic credibility. Part of that credibility comes from the manual’s claim that the film would be balanced, to respect “all different points of view.” This kind of balance (and I know that this notion of “balance” is flawed, but leaving that aside for a second) is rhetorically incompatible with its goals an Advocacy Film. The film’s theory of truth was thus confused.

Before I leave the Under the Gun website, I read its logline:

“In the gun debate, truth is the ultimate weapon.”

—

*When I say, “I spoke to lawyers,” what I mean is I emailed my ex-husband Brian L. Frye and he suggested I call Volokh.

**Eugene Volokh is also the guy behind of the hugely popular and highly entertaining blog The Volokh Conspiracy.

***At this point, I thanked Professor Volokh for speaking with me and made a feeble joke about how we doc folk tend to operate at a ninth-grade understanding of the law. He laughed and added, “Yes, well, I hear you guys often have the same problem when it comes to copyright, but that’s another story.” Note to self: call Volokh again.