Back to selection

Back to selection

2016: The Year in 10 Double Features

Adam Driver in Paterson

Adam Driver in Paterson The double feature has been a moviewatching mainstay since at least the 1930s. Their appeal is obvious: What better way to cap off a film than to delay real life for a few hours more with another one? Few of us catch double bills at a theater anymore, but their allure remains strong at home. As sites like Mashable and Uproxx reported this year, Netflix users can access double-feature-friendly micro-genres with ease. These days, the work of curating a dual bill of “critically-acclaimed gritty independent crime dramas” is practically done for you. You can even start the next film without having to push play.

In January, I ranked my favorite double features of 2015 on this site. This year’s list, like most pieces of writing you’ve read since November, is colored by the election of Donald Trump. I find it tough to apologize for that. Below, you’ll find 10 double features worth your time from 2016’s cinematic crop. Here’s to delaying real life for a few hours more.

10: National Bird and Eye in the Sky

Barack Obama authorized 10 times as many drone strikes during his presidency than George W. Bush. A key part of the president’s legacy, drone warfare — its legal, ethical, and psychological implications — was the subject of two films released this year. Sonia Kennebeck’s National Bird profiles the people behind the program: its soldiers and its victims. Kennebeck speaks with both a trio of PTSD-plagued drone operators and the survivors of a botched drone strike that killed 23 civilians in 2010. Her film highlights the human error, and human casualties, of a modern tool promoted for its alleged precision. Eye in the Sky, meanwhile, operates as an efficient little thriller and a skeptical look at counterterrorism in the 21st century. The film begins as a promo video for the military’s tech marvels, from Predator drones to surveillance drones the size (and shape!) of a beetle. Director Gavin Hood explores the legal ramifications of targeted assassination from the sky, off any battlefield and in a friendly nation. He arrives at a disarmingly dour conclusion: Despite our high-tech wizardry, the room for tragedy and error remains vast.

9: 20th Century Women and Certain Women

This would be a very different article if it weren’t for 80,000 people in three states. Likely many of our year-end lists would celebrate 2016 as a strong year for female-driven films — Arrival, Toni Erdmann, The Fits, Krisha, Love & Friendship, Isabelle Huppert’s triumphs — and ponder what this means for the industry heading into a Hillary Clinton presidency. But alas. Seven weeks after the election, Arrival now just looks like sad wish-fulfillment, and 2016 like a year we’d rather soon forget. The films of this double feature unfold as everyday portraits of American women: four in Montana (Certain Women) and three in Santa Monica (20th Century Women). Directors Mike Mills and Kelly Reichardt have assembled dream casts to tell their stories, from newcomer Lily Gladstone to a never-better Annette Bening. 20th Century Women brims with restless energy, from its biting dialogue and new wave soundtrack, while Certain Women plays out in the kind of low-fi, evocative quietude Reichardt has long mastered. They’re a reminder that, election disillusionment aside, 2016 was a remarkable year for female-centric cinema.

8: Silence and Sausage Party

What unites a pensive Martin Scorsese passion project and an aggressively crude riff on hot dogs as dicks? The Lord, of course. Sausage Party opens as a copycat of Toy Story, its protagonists a band of talking goods at a grocery store. Just as Woody and Buzz pine for Andy’s attention, they long for the all-powerful customers to purchase them off the shelves. They sing prayers about life outside the grocery store (“the great beyond”), only to learn their dreams of an afterlife are a lie. Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg aren’t subtle, and Sausage Party amounts to them cock-slapping us for 90 minutes with their thoughts on organized religion. Scorsese ponders a question that torments believers and nonbelievers alike: Why does god remain indifferent to suffering? Like Sausage Party, Silence is an adventure film; its leads encounter strangers along a journey who’ll either help or hinder their quest. The films arrive at radically different conclusions — apostasies for one, orgies for the other — but together they form a comically dissonant pairing on faith and doubt. Watch Silence first.

7: Nocturnal Animals and The Neon Demon

Two violent, vivid, L.A.-set thrillers — one directed by a fashion designer, the other set in the fashion world — Nocturnal Animals and The Neon Demon embody a cinema of giddy overstimulation. The latter is by far the more lurid of the two films here. A self-professed “fetish filmmaker,” Nicolas Winding Refn turns Los Angeles into a seductive, glittering deathtrap. His film plays like top-shelf giallo horror, complete with a frustratingly loose narrative and tight, menacing synth score. Refn is a pretty indefensible figure (see: every time he opens his mouth), but with The Neon Demon he’s found an ideal setting to unleash his stylistic excess. Almost tame in comparison, Nocturnal Animals is the Neon Demon you can take home to your parents. Sure, Tom Ford’s film opens on a group of nude, obese women dancing in slow motion, caked in glitter, but after that opening provocation he channels his fetish for the glamorous and garish to tell a coherent, almost conventional love story. Both films are hinged on big narrative gambits — the book-within-a-film in Nocturnal, the freakish final-act shift in Neon — and both find their directors at their most playful and visually intrepid.

6: American Honey and Green Room

Donald Trump’s America opens for business next month. No 2016 films offered such ominous signs of his rise than Green Room and American Honey, two abrasive accounts of poor white Americans at their most feral. Green Room pits its heroes against a network of white supremacists in rural Oregon. There’s no need to recap the white-rage overtones of Trump’s campaign, and certainly Green Room is more nasty fun than political statement. Still, viewed post-election, the film is an alarming document of the creep of white nationalism in America. Far more overt in its politics, American Honey depicts a group of poor, opportunity-less white young people who travel the country selling magazine subscriptions. Andrea Arnold brings an outsider’s eye to the country — its highways, its music, its crass commercialism. The film has an explicit reference to Trump, and it speaks to the climate in which he rose: A nation of impoverished, undereducated, mostly white people with no better alternative than to hop on board with a charlatan behind the wheel. No satire of America seems too over-the-top after November 8.

5: The Handmaiden and Love & Friendship

Every love story begins with a bit of deception. Without it, how do we convince another person to spend a night, a year, a lifetime in our company? We begin as salesmen for ourselves, showcasing our strengths and burying our flaws in fine print. The Handmaiden and Love & Friendship turn romance into a game of chess. Propelled by deceit and one-upmanship, these stories revel in the machinations of the seduction process. In Love & Friendship, a recent widow connives through a series of long-game maneuvers to land wealthy husbands for herself and her daughter. She manipulates those around her with expert ease, and endless wit. The Handmaiden centers around a volatile love triangle, which devolves into a series of betrayals and secret alliances (think Wild Things, only sexier). The three leads here are in it for love, for money, and for the thrill of playing a most dangerous game. Two period films heavy on costumes and sexual calculation, The Handmaiden and Love & Friendship get off on the lies we tell to win at love.

4: Elle and Things to Come

Why do Isabelle Huppert’s characters do what they do? It’s a tough question. For more than 40 years, Huppert has turned in performances of defiant, icy ambiguity. It’s rare to hear Huppert reassure audiences over voiceover narration. Instead, we’re left to rely on her physicality, and in particular her face, an instrument so evocative it’s spawned a museum exhibition. Huppert returns to the psychosexual unease of The Piano Teacher with Elle, a film about the repulsive sex lives of others. Sex has never looked so casually scary, from rape to infidelity to the crass fantasies of young men. At a recent appearance at Lincoln Center, Paul Verhoeven deadpanned, “Sexual intercourse can be pleasurable.” Other times, his film implies, it’s where our worst impulses surface. Mia Hansen-Løve directs Huppert in the far less confrontational Things to Come, another film in which a middle-aged Parisian woman has her life upended by those around her. Hansen-Løve, a young filmmaker, finds beauty in the resilience of an aging woman faced with infidelity, death, and a younger generation she understands less every day. Her film, like Elle, foregrounds an actor who’s starred in 100 films and continues to surprise and startle us.

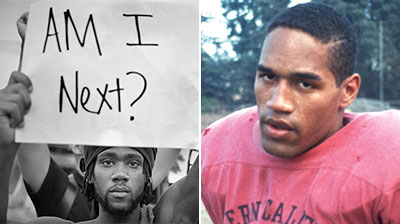

3: O.J.: Made in America and 13th

An eight-hour audit of America’s relationship to race, gender, class, and celebrity, O.J.: Made in America mines a sensational story for sober truths. Here is the sad saga we all know, or think we know, told anew. Director Ezra Edelman strays from the scandalous details of the trial to explore how O.J. became, first, an innocuous celebrity beloved by whites to, post-arrest, a civil rights icon within the black community. In Edelman’s hands, O.J.’s story becomes a rich case study for our contradictions (and outright failures) as a country. A traditional advocacy doc, 13th gives further context to how an affluent, apolitical tool like O.J. could become a symbol of black oppression. Ava DuVernay’s doc charts the rise of mass incarceration in the United States and its impact on black and Latino communities. From racially biased drug laws to police brutality, her film addresses the deep distrust many people of color have against cops, politicians, and the courts. 13th outlines the history of criminal justice abuses that would lead an angry, mostly black jury to find an obvious murderer innocent in 1995.

2: Moonlight and The Fits

Two formally audacious depictions of black youth in America, Moonlight and The Fits offer film programmers a double bill that sells itself. Here we find two of the most acclaimed films of 2016, both made on small budgets by young directors. Moonlight fractures the life of a young man into three distinct episodes as he finds his identity, sexual and otherwise. From its first shot, Barry Jenkins’ film overflows with cinematic verve. It unfolds not as a three-act narrative but as a piece of music: plotless, each segment a variation on a theme. The Fits moves with a similar, even more atmospheric logic. Anna Rose Holmer’s debut charts the growth of a pre-teen girl whose peers begin to suffer from epileptic fits. Her daring take on the coming-of-age film is light on plot, heavy on images and sounds that stir the soul. Just try to forget the film’s closing dance number. Moonlight and The Fits tell stories we rarely see, in a way we’ve never seen. Bonus: Both filmmakers support the idea of this double feature.

1: Paterson and Manchester by the Sea

Few phrases rankle the mourning liberal right now more than “working-class white men.” These are the people, we’ve been told, who handed Trump the election. Paterson and Manchester by the Sea tell the quiet, unglamorous stories of two such men; they are, also, the 2016 features I found most transformative, humane, and generous. With Paterson, Jim Jarmusch depicts the routines of working-class life as a chance to perfect ourselves as people. Imagine Groundhog Day, only our protagonist has already achieved the inner peace Bill Murray struggles to find. Paterson drives a bus, a job most of us wouldn’t want, but he doesn’t let that cloud his mind. He finds inspiration in the everyday encounters of work, which he channels into his art and personal life. Jarmusch crafts Adam Driver’s character as something of an ideal modern human: humble, kind, creative, intellectually curious, assertive when he needs to be. He offers a blueprint for how to treat others, and treat ourselves, in a time when division comes easier than compassion. As devastating as Paterson is tranquil, Manchester by the Sea tells the story of a janitor who abandons his work routine to look after his teenage nephew. Casey Affleck’s Lee is a broken man, one who greets each day with indifference at best. He’s stopped living; for him, if anything, work offers a convenient distraction from grief and guilt. Both films end on slyly hopeful notes: Paterson and Lee don’t triumph, but they’ve at least found reasons to get out of bed in the morning. For the purposes of today, that’s enough. These two films — apolitical, tender, deeply funny — speak to the daily tests we face as working people in this country. Alyssa Rosenberg recently urged us to stop speculating about working-class white men and see Loving. It’s good advice, to which I’d add the films of this double feature.