Back to selection

Back to selection

Twin Peaks: The Return: “Something is Missing”

Catherine Coulson in Twin Peaks: The Return

Catherine Coulson in Twin Peaks: The Return To a generation viewers groomed by two and a half decades of “outside the box” television ranging from X-Files, Northern Exposure, and Six Feet Under to the arabesque mysteries of Lost, Broadchurch, The Killing, True Detective, and Westworld (to name but a few), the hype over Twin Peaks must have always felt overblown.

Those of us who lived it the first time around can only say, “Trust us, you had to be there.”

Played straight (maybe even a little corny), but with a twist, Twin Peaks captured the American imagination and became the must-watch event of 1990. Simultaneously nostalgic and revolutionary, at once emulating and pillorying primetime soaps of the era, with “Who Killed Laura Palmer?” co-creators David Lynch and Mark Frost saw, and raised the stakes on “Who Shot J.R.?” Twin Peaks took the piss out of teen dramas like Beverly Hills 90210 by removing the homecoming queen from the board and scrambling the pieces. Lynch pulled back the curtain to suggest an out-of-whack universe reeling from a cosmic violation, a crime that could not be solved with the steady logic of a Dick Wolf Law & Order procedural. This case required a steady diet of mysticism, cleromancy, spit-take hot coffee and cherry pie.

Super-conscious of the genres whose tropes they mercilessly upended and applied to their own ends, Lynch and Frost keenly paid homage to their influences. They cast actors known for iconic roles, including Mod Squad’s Peggy Lipton, for a dash of hipster cool, and Piper Laurie, the mother in De Palma’s Carrie, for a hint of supernatural torment. They framed a soap opera within their soap opera, often zooming-in on a TV screen where the fictional soap Invitation to Love is on the air. They honored the legacy of “event television” with a double-barreled homage to The Fugitive: MIKE, who first appears in Twin Peaks in the form of Phillip Gerard, is an obvious allusion to lawman Lieutenant Gerard, who relentlessly pursues Richard Kimble. But Gerard (MIKE) is also a one-armed man[1], just like the killer Kimble seeks. The Fugitive’s finale drew 30 million viewers, and remained the highest-rated episode ever for a TV series until 1980, when 83 million people tuned in to learn that (spoiler alert) Kristin Shepard shot J.R. Make what you will of the coincidence that Lynch closed-out the initial Twin Peaks cycle with the theatrical release of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me on August 28, 1992, almost twenty-five years to the day after The Fugitive’s finale aired on August 29, 1967.

25 Years Later

To the devout, those of us firmly embedded within what Andrew Bujalski eloquently called “the cult of faith,” Twin Peaks: The Return is nothing short of miraculous. (To skeptics, and the uninitiated, The Return must look like an endless loop of animator Don Hertzfeldt’s Simpsons “couch gag”).[2]

Twin Peaks: The Return may be the crowning achievement to Lynch’s career, an expectation-shattering masterpiece that both breaks new ground and grounds itself firmly within Lynch’s cannon, revisiting (and elaborating upon) many of his past obsessions, tropes and bugaboos. Though he has called the program an eighteen-hour film, there is true delight in receiving the program in weekly installments, like opening a fortune cookie filled with a Möbius strip of familiar, yet uncanny images, words, sounds and songs. Like Hawk’s map, the show’s contents are both “very old” and “always current.” Twin Peaks: The Return is a living thing.

And yet, like everything in this Twin Peaks world, there is a paradox. Even as Twin Peaks: The Return bristles with life, it reflects the void left behind by those who are no longer with us. Every frame emanates a melancholy that mourns the passage of time. Lynch and Frost perfectly capture this sense of loss in scene in Episode 11, in which fans (finally) learn the fate of the romance of Dana Ashbrook’s Bobby Briggs[3] and Mädchen Amick’s Shelly Johnson. A beautiful nugget, this scene, unfolds with compact precision. Yes, Bobby and Shelly did indeed get married! And, they had a child together — Amanda Seyfried!

Alas, we also learn, in an instant — by how they are positioned around the table, and how they look at one another, and the words they use — that they are now estranged. The economy of the story-telling is staggering. Amick’s expression flips from concerned, scolding mother to giddy school-girl when Red (Balthazar Getty) taps on the diner window. Ever attracted to bad boys, from Leo to Bobby, Shelly has now moved on to Red. Ashbrook’s expression — disappointment, jealousy, regret — tells the rest of the story.

Other losses are more resonant. The late Jack Nance’s Pete Martell and dearly departed Dan O’Herlihy’s Andrew Packard, both of whom we presume were killed in the series finale’s bank explosion, are nevertheless deeply missed. Lynch and Frost have worked around the real life deaths of Frank Silva (BOB) and Don S. Davis (Major Briggs) by repurposing old footage. In the case of David Bowie, his Phillip Jeffries telecommutes into the story from time to time but is never seen.

Twin Peaks: The Return will be remembered as the final credit of a number of actors who passed during or after production wrapped. Miguel Ferrer’s acerbic deadpanning Albert, who contrasts perfectly against Lynch’s genially jovial Gordon Cole, is a series highlight. It’s a tragedy that the character who quipped “What happens in season two?” (if that’s a possibility) won’t be around to find out.

More personally, Mark Frost’s own father, Warren Frost (Doc Hayward), makes an appearance via Skype to chat with Sheriff Truman. Entertainment Weekly’s Jeff Jensen put a fine point on this moment with the observation that the scene aired on Father’s Day, “a bittersweet tribute from Mark to his dad, from the show to one of its few, admirable father figures.” It is also not a coincidence “the other” Sheriff Truman, Frank, played with bedrock gravitas by Robert Forster, is concerned with his brother Harry’s failing health.[4] With surgical precision, Frank, perhaps as the voice of Mark Frost to his own father, implores his brother, “Harry, do me a favor: Beat this thing.”

As a matter of course, everything in the Twin Peaks canon lives under the shadow of death. From its inception, the raison d’être for Twin Peaks has been to solve the murder of a dead teenage girl, wrapped in plastic, floating downstream.

Poughkeepsie, NY — April 8, 1990

When I implied earlier that I “lived it,” meaning I watched the series in real time, I made a slight exaggeration. On Sunday, April 8, 1990, late into spring semester of my freshman year at Vassar, the Twin Peaks pilot debuted on ABC. The series aired weekly over the next seven Wednesdays. Juggling a full course load, complete with term papers, end-of-semester reading, and final exams — to say nothing of jockeying to reserve the lone common room TV —made watching the episodes as they aired a non-starter.

Instead, I sent urgent word home, to Baltimore, for my mom to tape the show. Not trusting her to set the VCR to record properly, I implored her to please, please, please record it with the TV turned on, just to make sure it was recording.

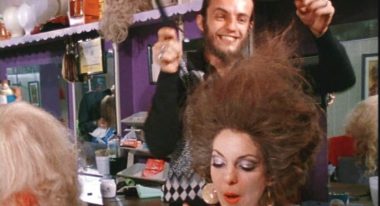

A note about my mother: she ignited my interest in and indulged my love of movies. When we first got a VCR, we’d go to the video store where she introduced my bother and me to the work of Woody Allen, Mel Brooks, Roman Polanski, Hal Ashby, Richard Lester, Stanley Kubrick and Francis Ford Coppola. We were probably too young to watch The Godfather as 3rd and 4th graders. Of course, when I was three, my mom was on the set of John Waters’ Female Trouble, an extra in the beauty parlor sequence, her hair being teased silly by Dribbles. (I was definitely too young for John Waters.)

It should come as no surprise to learn that she adored Twin Peaks. The task of recording the show went from a chore to a weekly ritual. She recorded each episode, and then afterwards she called me, as only a mother can, to discuss it with me. Knowing that the entire process was set in motion precisely because I couldn’t watch the show, she was so enthralled by the mystery, style, intrigue, and atmosphere of Twin Peaks, she couldn’t wait to share it with me.

On May 16, 1990, I packed up my Vassar dorm room for good, set to transfer a few miles upstream to Bard in the fall. I headed home for the summer. The season finale of Twin Peaks was set to air on May 23, 1990 and I had one week to catch up. That evening, I slid in the tape into the VCR, pressed play, and was consumed. First the pilot. Then episode two, and three, then just one more… I had planned to spread it out over the course of a week, but I couldn’t stop.

That evening, I watched the entire season in a single sitting. Note the date: May 17, 1990. Could this the first documented instance of “binge watching?” There is little doubt — with the possible exception of The Prisoner — that Twin Peaks is the first truly binge-worthy series. It is certainly one of the first series designed with an entire canon in mind, an arc for its own mythology and grand designs of the entire series as a single work of art, rather than a bunch of self-contained sequential pieces. Twin Peaks is built to stand up to multiple viewings, engineered to be watched in long continuous stretches and constructed to withstand excessive parsing by inquiring minds.

The following week, on Wednesday, May 23, 1990, I watched the finale to season one, as it was broadcast. Live. For the first time. With my mom.

The last time I saw her in person, about a month before she passed, I made a surprise visit back home. On hospice care, she was frail, breathing with the aid of oxygen machine, tubes in her nose, draped around her ears.

She died from lung cancer on October 10, 2016.

When Margaret Lanterman (the Log Lady) makes her first appearance in the debut episode of Twin Peaks: The Return, she is framed in a single shot, cradling her log in one hand, a telephone receiver in the other: “Hawk, my log has a message for you: Something is missing and you have to find it.”

This moment is EVERYTHING.

Prior to the debut, there was wide speculation about whether any of scenes featuring Catherine Coulson, who died on September 28, 2015, were completed in time.[5] Obviously aware of her failing health, Lynch and Frost wrote stand-alone scenes for her, and filmed them simply. She appears alone, frail, her hairline ravaged by chemo. She speaks on the phone to Hawk, oxygen tubes in her nose, draped around her ears. She delivers her coded lines with an urgency that suggests that she knows her time is limited. It is impossible to watch this scene and not feel that jolt of electricity, the revelation that you are receiving a message from beyond. Lynch and Frost are keenly aware of this effect.

Ten episodes later, Coulson/Margaret delivers the greatest monologue of the entire Twin Peaks canon, a meditation on mortality worthy of Hamlet, awash in a waterfall of Lynchian mythology:

Hawk, electricity is humming. You hear it in the mountains and rivers. You see it dance among the seas and stars and glowing around the moon. But in these days, the glow is dying. What will be in the darkness that remains?

Each time she comes to deliver another critical message, I see three things: I see Margaret Lanterman, the Log Lady, in the narrative context of the story itself; I see Catherine Coulson filming critical scenes for Lynch and Frost, a trooper and a professional to the end; and I see my own dying mother, ravaged by cancer.

“…Now the circle is almost complete…”

She holds the phone, speaking with such urgency, and I am transported to my freshman year dorm room. I hold the receiver to my ear, and my mom is dying to talk with me about this amazing new show I asked her to record. (Is this that place, you know the one, where it all began?)

“…Watch and listen to the dream of time and space. It all comes out now, flowing like a river. That which is and is not.”[6]

Now, I watch (and listen) alone. “Something is missing.” Could it be Phillip Gerard’s arm, with the tattoo that reads “Mom?”

Is this how it will feel, when its over, and there’s no one to call?

[1] Take note, because it might mean something: MIKE amputated his arm to remove his evil oath with BOB that read, “Fire Walk With Me.” Phillip Gerard lost his arm in a car accident, his tattoo said “Mom.”

[2] This brilliant meditation that evolves the series’ iconic characters into the future where they become mere abstractions, offers a close approximation of what it feels like to watch Twin Peaks: The Return. The moment where Homer tears at the very fabric of the universe presages the moment in episode 11 when Gordon Cole, played by David Lynch, stares into a cosmic abyss, where the Woodsmen await. Is the “attention cube” an approximation of the giant plexiglas box from Episode 1? When Marge mentions the Dark Lord of the Twin Moons, I imagine BOB or Mr. C. Does jellyfish head Homer’s repetition of “d’oh” not anticipate Cooper-cum-Dougie “Mr. Jackpots” Jones’ adventure in the Silver Mustang Casino — “Hell-oooo?!!!” Meta-footnote: The Simpsons and Twin Peaks debuted four months apart in 1990, and in addition to changing the television landscape for ever, the shows are linked in ever more interesting ways thanks to The Return.

[3] Part of the fun of The Return has been getting reacquainted with old friends, as if we are all getting caught-up at our twenty-fifth reunion. Ashbrook’s quarterback swagger has mellowed. His chiseled cheekbones fleshed out, his menacing eye brows now convey empathy, and tousled dark brown hair now grey.)

[4] Played in the original series by Michael Ontkean, who is very much alive as of this writing, but for reasons I know little about, was not invited to participate in The Return, the physical absence of Harry (and Ontkean) from the program is noteworthy.

[5] In contrast, David Bowie had been scheduled to make a return appearance as Jeffries, but unfortunately passed away from cancer on January 10, 2016, before he could film his scenes.

[6] Rebekah Del Rio’s haunting rendition of “No Stars”, penned by Lynch himself, reinforces this sentiment: “My Dream is to go to that place. You know the one. Where it all began…You said hold me, hold me hold me. Don’t be afraid, don’t be afraid, we’re with the stars.”