Back to selection

Back to selection

David Lynch and the Nightmarish Meanings of his Hollywood Star Casting

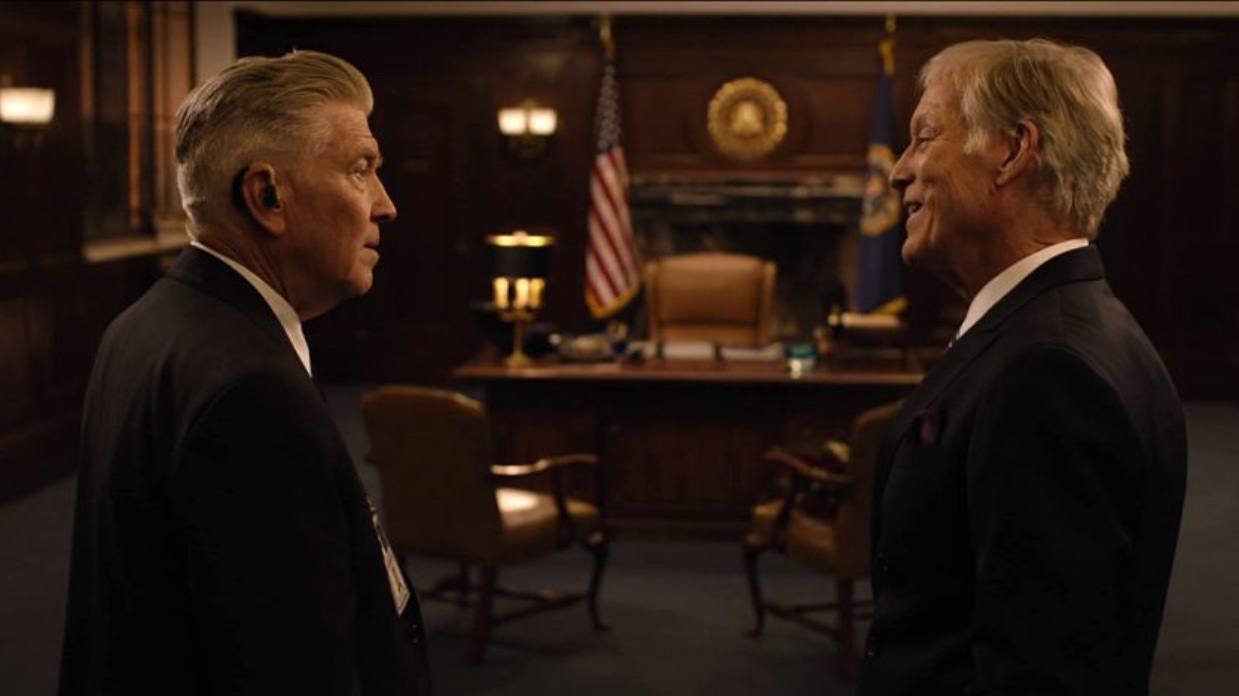

Twin Peaks: The Return

Twin Peaks: The Return In episode four of Twin Peaks: The Return, an older gentleman has an obscure conversation with Gordon Cole (David Lynch) as he escorts him to the office of FBI Chief of Staff, Denise Bryson (David Duchovny). Their scene together is short but just by his brief appearance Richard Chamberlain evokes a mass of associations in the viewers who recognizes him, maybe as Cannon Films’ Allen Quartermain, maybe as the ambitious priest with impure thoughts of Rachel Ward in The Thornbirds, or maybe as Julie Christie’s husband in Petulia. An icon of classic television thanks to his performance in the prime-time medical soap, Dr. Kildare, Chamberlain is gay in real life. His walk with Cole down the halls of the FBI signals to a cinema-literate audience that the Bureau is a wholesome but progressive place, thereby making a perfect segue into Cole’s impassioned speech in support of Denise’s rights as a transwoman: “You were and are a great agent. And when you became Denise, I told all your colleagues, those clown comics, to fix their hearts or die.”

I’m not the first person to write about Lynch’s genius at casting, but I specifically want to look at how he uses the extratextuality of classic Hollywood stars to inform his films. Lynch’s environments are often so esoteric, yet these connotations and connections outside of his universe give the viewer fundament to build on as they try to grasp the obscure events happening onscreen. Chamberlain isn’t the only actor of this era to appear in The Return. Returning from the original series we still have the two stars of West Side Story, Richard Beymer and Russ Tamblyn, plus Don Murray, who I’ll address in-depth later.

Lynch has exploited the extratextuality of his performers for nearly his entire career. Starting with Blue Velvet he opposes two types of Hollywood as his representations of good and evil. Laura Dern’s suburban mom is played by Hope Lange, the Golden Age ingénue of Peyton Place, while Dean Stockwell and Dennis Hopper, exemplars of the iconoclastic independent filmmaking that challenged the waning studio system, are the villains. In Wild at Heart, real-life mother and daughter Diane Ladd and Laura Dern reenact a perverse subversion of the relationship between Dorothy and The Wicked Witch in The Wizard of Oz. (The reference is evoked less subtly in the end of the film when Sheryl Lee appears to Nicolas Cage in a vision as The Good Witch.) There are more examples, but I’ll just end by pointing out the presence of a top star of musicals of Hollywood’s Golden Age, Ann Miller in Mulholland Drive. When Naomi Watts’s aspiring actress character arrives to look at an apartment, Miller is Coco, the manager who greets her. Watts’s youth and big dreams are a harsh contrast with the 78-year-old Miller, who seems to symbolize the disappointment and decay that happens to all beautiful things in Los Angeles.

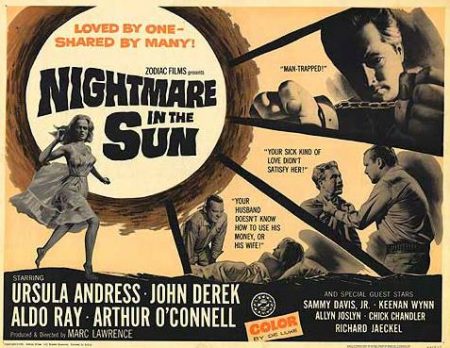

Essential to effecting Lynch’s vision is his long-time casting director, Johanna Ray, who has collaborated on every one of his feature films since Blue Velvet, plus his television work. Ray’s son, Eric Da Re, played the abusive and unstable Leo in the original Twin Peaks, and is Johanna’s child with 1950s tough-guy actor Aldo Ray. Aldo’s career began with instant success and he continued to work with major directors like George Cukor, Michael Curtiz, Raoul Walsh and Anthony Mann, until alcoholism worsened his strident temperament. In the last decades of his life, his work was limited to schlock horror, B-action movies, and even a (straight) appearance in a pornographic Western. Although some of them, like Psychic Killer and Don’t Go Near the Park, have cult reputations, Aldo’s demons doomed his career. On the cusp of his breakdown, in 1965 he starred in John Derek’s directorial debut Nightmare in the Sun.

I want to digress here a bit because John Derek’s life could be an unrealized plot from the Lynchian universe. A beautiful and adored Hollywood star, a favorite of Nicholas Ray, he quit acting at the height of his career to become a filmmaker, casting in his films a series of child brides/muses. Derek married Ursula Andress, the first Bond girl, when she was 19 and starred her in his first two films. While he was with his next wife, Linda Evans, he met a 16-year-old Long Beach high schooler, then took her to Europe to make a film and be his girlfriend. Derek wrote, directed, shot, operated and edited his films, a feat you would think auteurist film critics would appreciate, yet his output is reviled by reviewers and audiences alike, unless they’re watching to ogle the Long Beach high schooler Derek married and renamed Bo Derek. I had never watched one of his movies until recently, and I thought it was fucking fascinating.

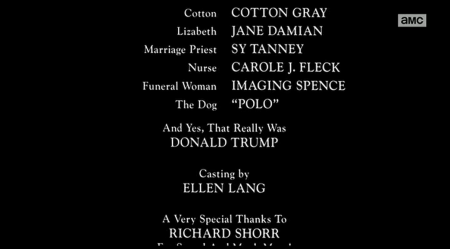

His final film, Ghosts Can’t Do It, marked the end of a long collaboration with fellow actor-director Don Murray, who plays Lucky 7 insurance president Bushnell Mullins, aka “Battling Bud,” on Twin Peaks: The Return. Murray, like Derek, started his career as a Columbia Pictures leading man, co-starring in Bus Stop with Marilyn Monroe and his first wife, Hope Lange — yes, the same Hope Lange from Blue Velvet. In Ghosts Can’t Do It, Murray plays a supporting role as Winslow, the business partner of Anthony Quinn. Quinn is hideously rich and married to the young, succulent Bo Derek, but when a heart attack incapacitates him he takes his own life. He finds himself in heaven, an out-of-focus soundstage administered by angel Julie Newmar, where he is to be eternally deprived of the concupiscent gifts of Bo. By filming almost entirely in close-ups and concretizing Quinn’s absence-presence by the most generous of eyeline matches, John Derek disorients the viewer to draw us into the limbo of Quinn’s unstable existence. Murray is mostly there to look flummoxed when Bo speaks to herself but he also has a magical dance scene with her where she does that great dance move, “the dolphin.” And he also introduces her to the members who sit on the board of Quinn’s business empire, among them Donald Trump playing himself.

This is the water and this is the well.

Drink full, and descend.

In Twin Peaks: The Return, David Lynch awakens us to the nightmarish knots that tie our world together with dark forces. In reality we’re also enmeshed in a matrix of images, all of which seemingly end with that failed actor and businessman, President Trump. We look to the last two episodes of Twin Peaks: The Return to show us our future.