Back to selection

Back to selection

Time and Tempo

by Nicholas Rombes

Seducing the Future

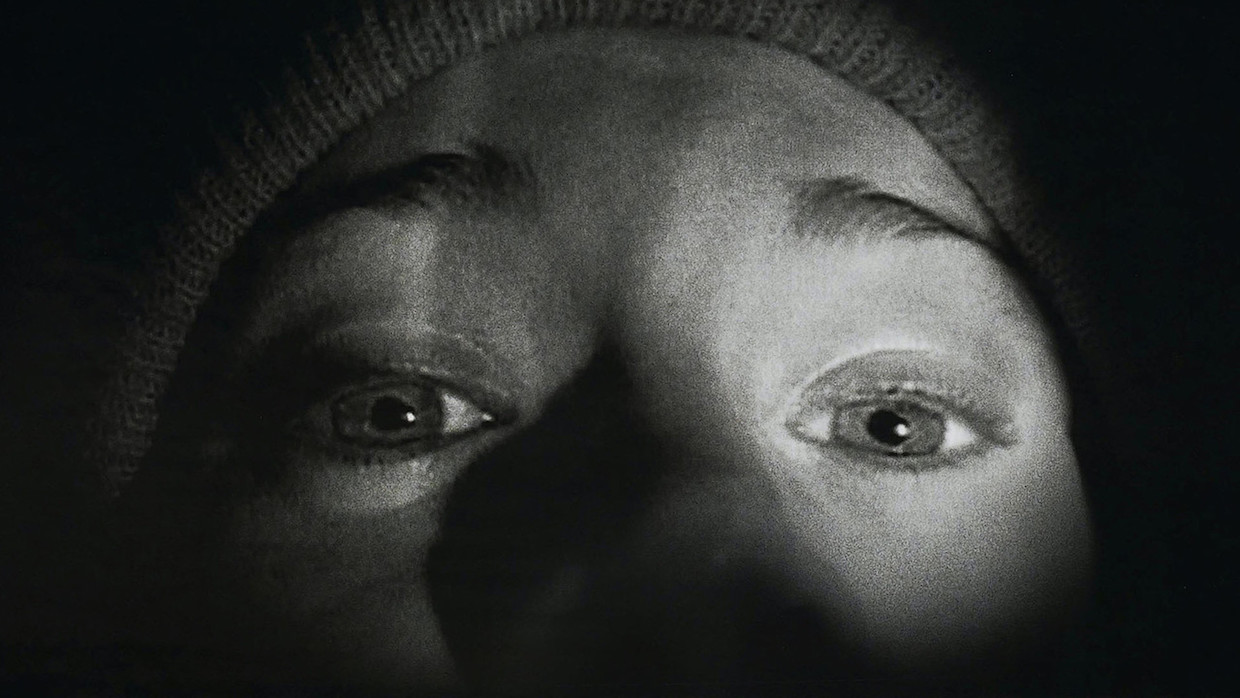

The Blair Witch Project

The Blair Witch Project To say that the transformations that film and film technology have undergone since Filmmaker’s inaugural year — 1992 — are revolutionary is an understatement. DVD was still on the horizon, DV camcorders were several years away and the notion of shooting and editing a full-length motion picture with no actual film seemed downright futuristic. There have been book-lengths’ worth of changes since that first issue, but here are just a few.

I. Metadata

The information surrounding a film has stretched far beyond mere publicity (the classical era) and merchandising (post-1977 Star Wars), becoming enmeshed within the very fabric of a film. If the film was primary, and all the attendant information surrounding a film used to be secondary, those distinctions have all but collapsed in the past 25 years, or even reversed. There are many potential names for this secondary material — bonus material, extra material — but I think the simple term metadata captures it best. That’s all the collateral material in orbit around the film that is not the film itself: deleted scenes, alternate takes and endings, director’s cuts, uncut versions, extended versions, online mashups and remixes, online commentary, etc. In a larger context, this is (or was?) part of the postmodern shift where post-WWII suspicion about “master narratives” gave rise to a renewed interest in the stories that lay behind stories.

Art has always been, on some level, “about” itself. Yet novels like Paul Auster’s City of Glass trilogy (with someone named Auster featuring as the main character in Auster’s books), David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest (whose footnotes threaten to displace the primary text itself) and, of course, the self-reflexive impulse that gave such tension and energy to the French New Wave (where unmotivated asides, camera movement and editing became as or more important than the so-called plot), along with other post-war flowerings, challenged the notion of the authentic, the pure, the primary. All the material that was relegated to the margins has migrated toward the middle, often rearranging boundaries between the margins and the center. A film is now so much more than the film itself and, in fact, is often eclipsed by this more-ness.

II. Immersion and Pleasure

Engaging with a story — whether it be via reading or listening to a book or watching a movie — has always been an intensely interactive experience, as the weird, mysterious interplay between the reader or viewer and the book or film takes place in the deep folds of the mind. Interactivity is nothing new, but the ways in which we have come to interact, with film especially, have radically transformed the experience over the past 25 years. In her 2006 book Death 24x a Second: Stillness and the Moving Image, Laura Mulvey commented on DVDs and other playback devices that allow the viewer to control the temporal flow of a film: “The narrative drive tends to weaken if the spectator is able to control its flow, to repeat and return to certain sequences while skipping others,” she wrote. “The smooth linearity and forward movement of the story become jagged and uneven.” What began as Sony’s concept of “time shifting” in the 1970s was far more than a mere technical innovation — it eroded the boundary between viewer and film to the extent that the viewer is now part of the film, a process that has helped prepare the way for virtual reality.

Ours is an age of pleasure deferred. We want our movies to last forever and so they do, living on not in the traditional way of re-remakes or sequels but rather in the permanent state of lossless remixing that is the prime characteristic of digital media. It is a sort of permanent impermanence, as cinemagraphs (which composite a film’s video frames into animated GIF files, such that only a select part of the action on the frames appears to move) and less subtle animated GIFs proliferate on Tumblr and other sites. The shifting, transient spaces where movies are now watched harken back to the early days of cinema before they had found their architectural home. In When Movies Were Theater, film historian William Paul notes that “perhaps because movies first successfully appeared in architectural spaces not specifically designed for them, there seems to have been a sense that just about anything could be pressed into service as a movie theater… The movie palace, which would finally become the dominant form for first-run exhibition, did not emerge as an inevitable development.” And so, too, with our post-post-digital age, as movies continue to migrate.

Freed from the seductive confines of the movie theater, films are dispersed across time and space, existing unembodied like all other information: in the cloud. Since Filmmaker’s first issue, film has become a signal, not a site.

The Blair Witch Project (1999) — that pre-digital digital film — remains a key document of the era in which Filmmaker was born. It’s a splice in time stitching together analog (the parts shot in 16mm) and pre-digital (the parts shot on Hi8), and it’s fitting that it appeared at the cliff’s edge of the old millennium, only eight months after the other landmark primitive digital film, Festen (The Celebration). During those heady days film once again became as supercharged, courageous and unpredictable as it had been in its early, experimental days when its grammar and visual logic were just being invented. Revolutions are short, and the horizon on the digital revolution has closed. We have returned to a conservative, even reactionary cinema of recycled stories and spectacularly dull aesthetics. Far from being dead, the culture industry is alive and well and replicating itself, virus-like, through the very digital media that once seemed so freeing and promising.

And yet the new experimentalists are inventing virtual reality at this very moment, creating new narrative methods and aesthetics. Just as it chronicled, explored and deconstructed digital cinema, Filmmaker will be there to trace, archive and promote the boldest storytellers of this new frontier. The future is there, waiting to be seduced.