Back to selection

Back to selection

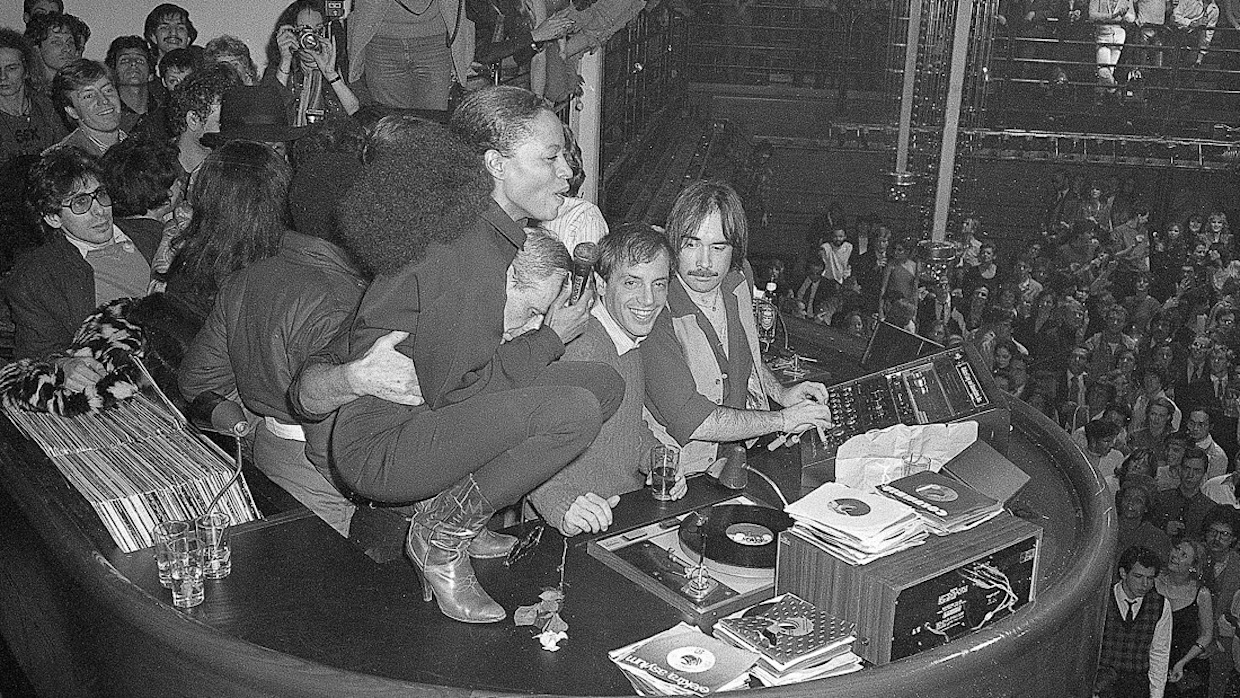

“It Came to Symbolize a Whole Era”: Editor Andrea Lewis on Studio 54

Studio 54

Studio 54 Andrea Lewis served as a co-editor on Citizen Jane: Battle for the City, a 2016 documentary on urban activist Jane Jacobs. The film earned strong reviews for director Matt Tyrnauer, who would hire Lewis to edit his next documentary: Studio 54. The film tells the story of the rise and fall of the iconic ’70s nightclub through the lens of its founders: Ian Schrager and Steve Rubell. Lewis spoke with Filmmaker before the film’s premiere at Sundance about the task of giving shape to this archival-heavy project.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Lewis: I was working with director Matt Tyrnauer and producer Corey Reeser on their film, Citizen Jane: Battle for the City, when the Studio 54 project came up. I was pretty enthusiastic about the subject matter and excited that they wanted to utilize photography of the time to tell the story in a unique way. Before becoming an editor, I had gone to art school. I have an MFA in sculpture and worked for artists making and installing their work. Part of the reason I was hired for the job was because my background in art could bring a different perspective to the film. I was familiar with the photographers and artists of the time, and being given a lot of photography to use, as well as archival material and new interviews, I was eager to bring all these elements together.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Lewis: The mythology surrounding Studio is made up of a lot of great, funny (and often racy) stories about the goings on and inner workings of Studio 54. Unfortunately, we couldn’t include them all. We had to kill a lot of darlings to distill the final story. It took some discipline not to get lost in all of those stories. I wanted the audience to experience the decadence and visceral nature of Studio, but at the same time not deviate too far from the bigger story, which was that of Steve and Ian.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Lewis: Our approach was not to explain too much, but to be more about impressions than words. With the off-type music, it became very visceral. The test screening was extremely important because half the film is about a very complicated court case. We were so close to it, we had to make sure the audience could follow the story and that the details were tracking. And also to make sure that it was compelling as a whole and fun to watch.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Lewis: I started out as a tape op, then an assistant editor, at Paramount Digital Design P(d)2, which was Paramount Pictures’ main title division. After that, I worked as an editor at a production company, and then to working freelance, cutting all kinds of marketing materials for films. Because you have access to the films themselves as a source, you have this unique opportunity to be able to dissect how they are put together, to analyze an edit that Michael Kahn made or how Gore Verbinski crafted a scene. And then of course you have all of the behind the scenes footage. The immersive nature of those projects was the perfect training ground for me for working in the art form of documentary.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Lewis: Not to sound like a commercial, but I’ve always used Avid. I think because it is industry standard, and almost every place I’ve worked uses it. Working on a project of this scope, Avid works well for sharing projects and bins, and I find the interface is very intuitive in a way that allows me to forget about what buttons I’m pushing and focus on editing.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Lewis: From the very beginning we were going after a look and feel for the film that would be counter to everything else that’s been done before on Studio 54. But we weren’t sure at first what that would be. When we saw Glenn Albin and Susan Shapiro’s 16mm film footage shot inside Studio, we were all taken by the film’s luminance and fly-on-the-wall perspective. I really wanted to sink into that liquid feel of the footage, to feel suspended in it. Slowing it down and setting it to off-type music captured that eerie yet beautiful sense of something trapped in time – a paradise lost. Their footage really unlocked what the tone of the film would be.

Filmmaker: What role did VFX work, or compositing, or other post-production techniques play in terms of the final edit?

Lewis: The archival material and photography from the ’70s presented a unique opportunity to use the inherent imperfections, but we also had to clean up a lot of the headlines and paper elements. I think simple, designed graphics can really elevate the look of a film, and that it is a very important part of the filmmaking process to incorporate them in a graceful way.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Lewis: Bringing the archival to the forefront really brought a human quality to the film. What I hadn’t expected was how much Studio 54 meant to the people who worked there and went there. It was more than a moment in time, or a reminiscence of youth. It came to symbolize a whole era, a collective experience well beyond a nightclub.