Back to selection

Back to selection

“I Saw the Film as a Mystery — To Try and Understand Someone Who Didn’t Want to be Understood”: Matt Wolf on His Doc, Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project

Recorder: The Marian Stokes Story

Recorder: The Marian Stokes Story With Matt Wolf’s Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project opening today at the Metrograph in New York, we are reposting Scott Macaulay’s interview with Wolf prior to the film’s Tribeca premiere. Wolf will be doing a number of Q&As opening weekend with various moderators, including, tonight Lynn Tillman, as well as, this weekend, Charlotte Cook, Melissa Lyde, Sierra Pettengill, Collier Meyerson, Stuart Comer and Macaulay (the latter at the Saturday, 1:15 PM screening).

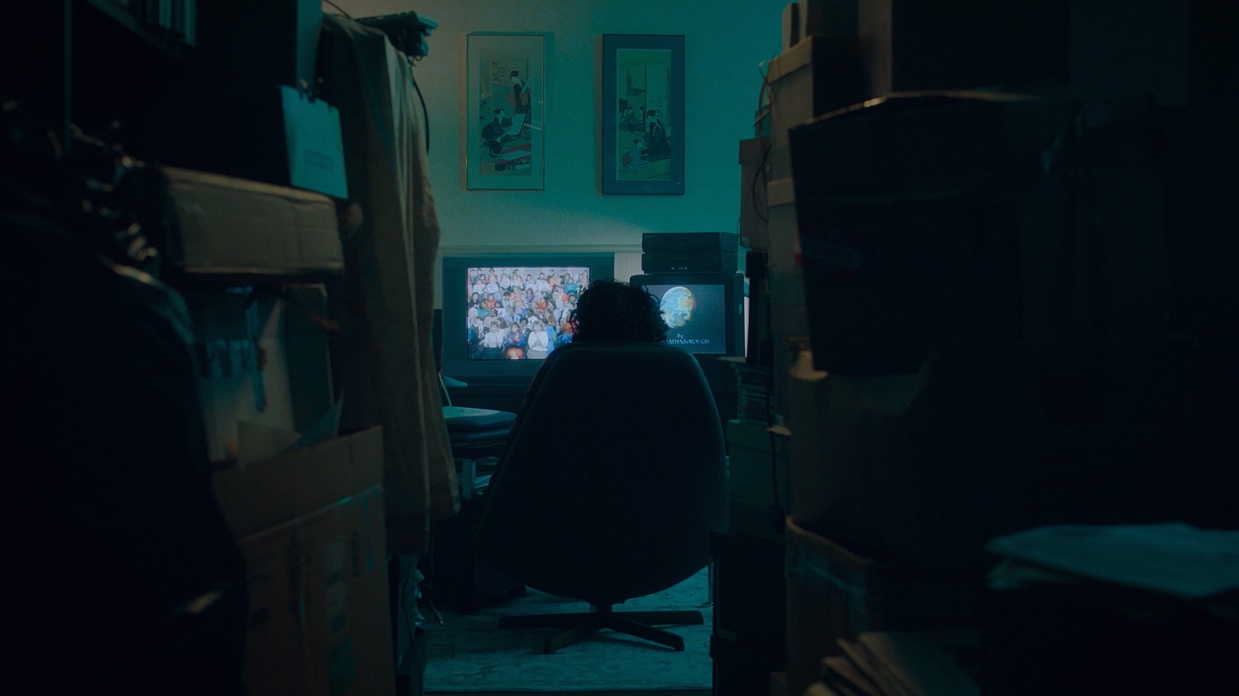

From 1979, just before the launch of CNN, to 2012, when she passed away, Marion Stokes — an African-American Philadelphia woman, communist, public access television host, collector of Apple computers, media critic — recorded continuous streams of 24-hour-cable news on VHS tapes that piled, floor to ceiling, the various apartments she owned throughout the city. (Born into wealth, Stokes, a fan of Steve Jobs, convinced her family trust to buy Apple stock at $7, long before the iPod.) Conserving stock by recording in extended play mode, she employed assistants who’d shuffle tapes in and out of the eight or so VHS decks that ran at all hours across her apartment. The result of her efforts is the “project” cited in the title of filmmaker Matt Wolf’s engrossing new documentary, Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project. This archive of 70,000 hours of footage — now preserved by the Bay Area Video Coalition — is a primary source telling of how America political discourse has succumbed over decades to the manufactured drama and hypnotic conventions of the cable news industry. Through Wolf’s artful montages, which mash up Stokes’s recorded news streams into evocative mini-essays on some of the key events and impactful periods of late-20th century American life, the film historicizes media style and form — everything from the stylings of both graphics and news anchors to the editorial framings given to the news events themselves — in order to tell a story that travels from ’80s critiques of “news as entertainment” to the “fake news” imbroglios of today.

But Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project is not just — or even predominantly — an essay film about the media. What makes the documentary so fascinating is the parallel it draws between restoring an archive and retrieving a life. As engaging and sharp-witted as she could be during her public access TV appearances, the little-known Stokes was domineering, controlling and, finally, vexingly withdrawn in her personal life. Recorder: The Marion Stokes’s Project doesn’t shy away from revealing the pain she caused her son and first husband. As for her second husband, her colleague on her television show, their’s was both a great love affair as well a heartbreaking tale of two people who reclusively found solace in each other at the expense of their own sons and daughters. Furthermore, Stokes’s media gathering activities as seen here could be interpreted by some as less media criticism than a psychological cousin to hoarding.

It’s to Wolf’s enormous credit that while he doesn’t shy away from Stokes’s darker qualities, he also sees past them to identify in those countless hours spent in front of TV screens a larger passion, purpose and commitment. It’s this inquisitive, open and perspicacious approach that makes Recorder: The Marian Stokes Project not just a fascinating film but an emotionally transporting one as well.

Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project is now playing at the Tribeca Film Festival and travels this week to Hot Docs. Screenings at the Montclair Film Festival and Maryland Film Festival follow. I spoke with Wolf by phone before the Tribeca premiere.

Filmmaker: I loved the film and really admired the way you threaded the needle here — how you blend a kind of sociological, media-criticism story with a love story, as well as, to some degree, a dialogue about possible mental illness.

Wolf: Thank you. I’m trying to do a lot. I felt like I struck that balance, but it was always a struggle. You know, is [the film] more about Marion, is it more about the archive, and how does Marion point to the archive, and how does the archive point to Marion? It was a tough balancing act.

Filmmaker: How did you first discover Marion and the archive? I’ll have to confess, I didn’t know anything about her.

Wolf: I don’t think many people do. When her collection was acquired by the Internet Archive, there was some media and press coverage. Fast Company, the technology blog, did a story that circulated on social media. I started looking into it [because] I like a challenging archive, and this one was kind of unprecedented. My producer Kyle Martin and I went to Philadelphia and met Marion’s son, Michael. He was living by himself in Marion’s apartment — probably the fanciest apartment building in Philadelphia — and was trying to organize all her stuff. We saw hundreds of Macintosh computers in their original boxes, all stacked up. And then we went across the street to the restaurant where Marion had her martini every day, and it was clear that this was an emotionally intense family story. And that’s how we kicked off our process: recognizing the possibilities of the archive but also that this was a unique family story. I wanted to learn more about Marion, [someone] who privately taped television for three decades, 24 hours a day. We started to learn things that didn’t seem to go together — like, she was a radical Communist activist. And then it all started to make sense why she was doing this — that there was a mission and purpose behind it.

Filmmaker: What role did the estate play in terms of the content that was allowed into the film?

Wolf: It was really collaborative in the sense that Michael is very committed to preserving his mother’s legacy. He’s had a complex and tumultuous relationship with her, but it had come full circle, and he put his life on hold to deal with her archive and her estate. He helped us obtain a lot of material and connect with a lot of people. And then we obviously worked with the Internet Archive to deal with her tapes, which was quite an involved process as well.

Filmmaker: You bring up the issue of possible mental illness — you talk about Marion being a hoarder. But it’s not a predominant theme of the film.

Wolf: I think a lot of people expected [the film] to be about a hoarder or some sort of pathological historian. I think, particularly with films that deal with a deceased subject, it’s really important to not do armchair psychoanalysis or to pathologize people, particularly unconventional people. I mean, [she had] a compulsion to record, but I never had an interest in trying to understand that from a purely psychological point of view. I felt it was inappropriate for me to make those assumptions [because] to pathologize what she was doing would be to discount a coherent mission and purpose. And I think [her purpose] was what I wanted to understand and to help other people understand, while also recognizing that there was a destructive and painful aspect of that. She made significant sacrifices that affected the people around her. I also didn’t want to idealize Marion. She was multidimensional in the sense that her relationship to other people, and to control, was complex. Her project was painful for people as much as they can recognize its value and her insight into pursuing it.

Filmmaker: There was never a suggestion in the film that she ever went back and watched anything she recorded.

Wolf: Yeah, [her work] was more about capturing and preserving than it was actually reviewing and analyzing the material. I do think she had a particular analysis of the media and the mechanisms through which it works, and she had her own politics, but there was a kind of agnosticism to [her project] in the sense that she saw value in retaining this information because she believed that bias and factual inaccuracy could shape historical narratives in problematic or negative ways.

Filmmaker: It’s fascinating because if someone had told me at the time about her project, I would have wondered why she was doing it. I would have assumed that the TV stations would keep everything. Of course, we now know that so much material we imagine to be archived has actually been lost.

Wolf: Yeah, any filmmaker or historian who works with television archives knows they’re very inaccessible. You can request material and pay to receive screeners, but that doesn’t include the “flow,” as they call it, of television with the non news — the talk shows, PSAs, local news content and commercials. So much of that kind of detritus from the media speaks volumes-about who we were at particular historical moments. This collection really captures that 24-hour flow from multiple network’s points of view.

Filmmaker: There has been sociological critique of television since the ’50s — the notion of the “boob tube,” and then, in the ’80s, there was Neil Postman’s book, Amusing Ourselves to Death, which criticized television’s ability to convey news due to its formal presentational elements.

Wolf: Yes, and how the onslaught of the 24-hour news cycle created a demand for content. I think Marian was concerned with what kind of stories would fill that void and how the flow of information over a 24-hour news cycle would obscure factual information that was evolving in real time.

Filmmaker: At the same time, this sort of critique isn’t really voiced by Marion in the film. We see her on public affairs shows where she’s not really talking about the media. Was the type of criticism we are ascribing to her now ever something she expressed or voiced during her life?

Wolf: The television show she produced was before the taping project began, and I characterize it as kind of a consciousness-raising program. The subjects they discussed were expansive and idiosyncratic and really interesting. We really mined those TV episodes to get clues about Marion’s philosophy, her politics, and just her point of view about the world. It’s the only real material that exists in a primary way where we hear her voice. In a lot of ways I saw the film as a mystery to try to understand someone who didn’t necessarily want to be understood. A lot of our insights come through the people who knew her. She hired this surrogate family of assistants who she confided in for decades. And her son Michael was really tapped into what she was doing and why. But yeah, there’s the speculative aspect to it because Marion is a very mysterious figure who didn’t really leave behind a lot of information about her life.

Filmmaker: Well, I feel like the montage scenes in the film are the answer to some of these questions I’m asking. I feel like they make the best argument for the value of her work. They are so fascinating to watch. I’m curious whose point of view, if any, you saw these sequences representing. I wasn’t sure if they were hers, or were mine, as they triggered my own memories of these events, or whether they were kind of reveries of the film itself.

Wolf: I think it’s a little bit of all three of those things. As I said, when we were making the film, I always kind of had to challenge myself: how does Marion point to the archive and how does the archive point back to her? And also, you know, we indexed this collection through her notes — Marion made handwritten notes on the spines of every VHS tape. So, that provided some clues about her enduring interests or preoccupations, whether it was Jesse Jackson or Oprah or the MOVE bombings. But it was also about how the archive could represent itself and show this passage of time in an unconventional way — not just through the big-ticket historical events that people are familiar with but also through the more marginal histories as well.

Filmmaker: How did you select the material for these montages out of so many hours of footage?

Wolf:I would choose dates from which to cherrypick from the collection and to digitize based to some extent on my own interests and, speculatively, a little bit on what Marion’s interests were. And also based on [dates] that were historically significant. As I scrubbed through several hundred hours of footage, I was marking stuff that I thought was visually compelling, stuff that I thought was interesting cultural history, and stuff that I thought would have been significant to Marion as she saw it. Working with my editor, Keiko Deguchi in constructing these montages I was always, in a sense, approximating Marian”s point of view as part of the way to better understand her, but I was also trying to approximate our collective point of view, our experience of history and the passage of time. Often I would insert something that was just interesting to me, whether it was the history of gay rights, or the representation of the AIDS epidemic — things I’ve looked at in other films. But, you know, [I would sometimes think], this is more about me and my interests, and the film needs to serve Marion’s story. So I would often remove stuff that just appealed to me aesthetically or appealed to my particular historical interest and reframe around things that represented her preoccupations, whether it was the representation of Cuba and communism, the representation of the media, issues of race and violence and the evolution of technology in tandem with the evolution of the medium of television itself. So that became the broader framework in which I was looking, but then of course, within these hours of tapes, we would just find interesting and unusual things that would become useful from a storytelling point of view.

Filmmaker: Still, organizationally, this must have been a huge endeavor, even if you’re scrubbing through. There must have been thousands of tapes.

Wolf: Oh, there’s 70,000 tapes. So dealing with the entire archive was obviously never a real possibility, but I like to develop a unique process for every film I do. And for the most part, all the films I’m making now grapple with enormous archives. I developed a process in which we had to actually index Marion’s full collection. We created with the help of archivists at the Internet Archive a conveyor belt in which we would take the tops off of file boxes where Marion stored her tapes. The tapes were stored spine up, and we would take a photograph of that box showing the spines of every single tape in the box. We had probably a thousand or more photos, and then we had to transcribe the metadata that she had written on these tape spines on the VHS tapes. And so we put a call out for volunteers and over 50 people from around the world signed up to help us. We created a Dropbox folder that had all those images and the collaborative Google spreadsheet and people would collectively transcribe the metadata to this database. And eventually one volunteer archivist in particular, Katrina Dixon, rose to the occasion and became more dedicated in a full-time way to completing the index.

And then my process was to actually use Wikipedia as a way to track both big-ticket historical events, but really also the obscure, weird ones — you know, like the day the Miss America pageant stage collapsed. I went through Wikipedia, which has a page for each year, and I just wrote a giant list of specific days that I thought might have interesting and relevant material on them. And Katrina would go through the index and find tapes that were as close as possible to the days and times that might cover these stories. And then I’d prioritize [that information]. Ultimately we digitized a hundred tapes with the help of the Bay Area Video coalition, who are preservationists and partners on the project. She recorded EP [extended play], so these were six-to-eight-hour tapes. Sometimes a tape would have nothing of interest on it and be totally random and other times it would be a gold mine of material. So I would scrub at 10 times speed through these tapes, just hitting markers whenever I saw something that was interesting, and I worked with assistant editors who would then pull these clips, and organize them for our editor who would then have material organized by subjects and dates. And that’s how we [developed] a pretty rigorous system to wrangle and search for specific things. But ultimately it was the things we weren’t searching for that were the most interesting.

Filmmaker: Did you always use the tapes for source material or sometimes go back to higher-quality sources?

Wolf: I always was drawn to the fuzzy, distorted, 4:3 look of VHS. I always thought that would be the aesthetic of the film, which is part of why the recreations are shot in a more contemporary way — to create a contrast. I came to really love the texture of VHS and the distortion and artifacts on it. It also, I think, emphasizes the ephemerality of the format that Marian was working on, and the urgency to preserve analog media that is literally disintegrating.

Filmmaker: Were there any technical challenges to doing that and then coming up with like a deliverable film by today’s standards?

Wolf: Yeah. I really owe a lot of credit to the Bay Area Video Coalition. They are just incredibly thorough and experienced at preserving analog media. There was one person working there, Kelly Haydon, who now actually works at [NYU] Fales Library, and she watched these transfers in real time assuring whenever possible that the audio levels didn’t drop out trying to capture the best picture. So I would characterize it as a preservation process, not just digitizing. We digitized in Pro Res at the highest level for archival material possible, and we leaned into the distortion and fuzziness as part of the look of the film.

Filmmaker: You worked with the law firm of Donaldson and Califf, who are often at the frontiers of Fair Use. I presume you are relying on Fair Use for most if not all the material in the film. What was that legal review process like?

Wolf: Before, making the film, we engaged them to see if it would even be possible and to explain our Fair Use strategy and how we wanted to use this material to tell the story. Part of the reason we were able to make this [Fair Use] case is that the film and the story itself is about media criticism. So part of the chronological use of the material enhances the Fair Use strategy of the film in addition to illustrating ideas that are critical of the media itself.

Filmmaker: How did you fund the film?

Wolf: We were lucky; we partnered with End Cue, a production company based out of Los Angeles. They come from Silicon Valley technology backgrounds are are working at the intersection of technology and filmmaking. They came on very early at the development stage and stayed with us as the kind of financing and production partners through the entire film.

Filmmaker: So none of the traditional doc funding sources?

Wolf: No, the film was funded by them. We didn’t get grants. The film is between a lot of spaces. It’s a character-driven story, but it also a film that is engaging with an archive in a somewhat experimental or unconventional way to represent a pretty expansive history. So, it’s not topical per se, but in other ways it is. We started this film before the notion of fake news was brought into the public’s consciousness by Kellyanne Conway and Donald Trump. The film has taken on a different kind of significance after that because in so many ways Marion was anticipating something like [fake news] and archiving was a means to, I think, resist the distortion of the truth through political forces within the media. She saw that beginning as early as 1979. But I didn’t want to make a film about fake news and I don’t actually have much to say about fake news. What I have to look at is Marion and her mission and seeing that she had insights about media and technology that were ahead of their time and that feel all the more all the more presicent today.