Back to selection

Back to selection

Extra Curricular

by Holly Willis

The Most Valuable Lessons: Filmmakers Remember Their Iconic Instructors

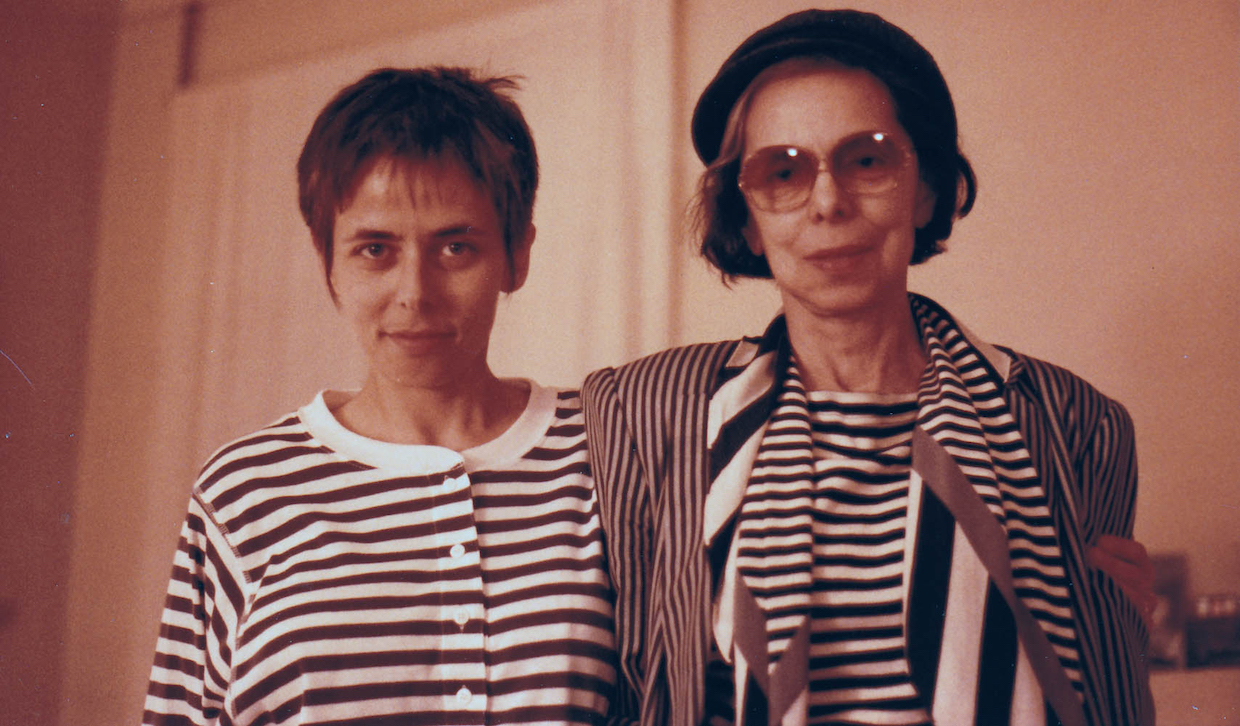

Candace Reckinger with her mentor, Shirley Clarke

Candace Reckinger with her mentor, Shirley Clarke Teaching is a complex act, but most of us standing in front of students in film classrooms have never been taught to teach. Instead, we recall the teachers who impressed us, then try to repeat some part of that practice and hope for the best, often never quite realizing the impact we are in turn having on our own students. Here, three current faculty members recall iconic instructors from their college experience, and the lasting effect of key ideas and behaviors.

Cauleen Smith on Lynn Hershman Leeson and Trinh T. Minh-ha

Interdisciplinary artist Cauleen Smith earned a BA in creative arts from San Francisco State University and an MFA from the School of Theater, Film and Television at University of California, Los Angeles. She is currently a faculty member in the School of Art at California Institute of the Arts. Smith studied with artist Lynn Hershman Leeson and filmmaker Trinh T. Minh-ha when she was an undergraduate at San Francisco State University in the creative arts program.

I credit Lynn Hershman Leeson with one of my films, Chronicles of a Lying Spirit. It came out of an assignment for her performance art class. I took what I learned from her to my other courses and expanded on it.

Lynn had a relentless criticality: She took the work of her undergraduates very, very seriously. She treated us like we were already artists, which was new to me. She was very exacting about what would make the work better, what would make it ready for the world. At the same time, she was really flexible and didn’t have hierarchies about what medium we could work in. Some people brought in dance pieces and others brought in poetry, and that flexibility has been a model for me ever since.

With Lynn, I remember getting critiques from her that felt scathing, but they weren’t. They were insightful and strong. I was a very young person and to hear someone say, “This isn’t as good as it could be, and you need to go back and make it better” was such a shock. So, I try to do that now with my students. I expect a lot from them. I don’t condescend to them. And what I remember so much about Lynn was the way she spoke to us: calm, thoughtful, engaged and blunt. She didn’t sugarcoat what she said. I’m so grateful to her.

I studied with Trinh T. Minh-ha for two years, and it was mind-blowing! It was the late 1980s and early ’90s, and she had us reading all this poststructuralist theory. It was just being translated—Roland Barthes, Michel Foucault—and she was bringing these mimeographed third-generation copies from France. The language was hard to read, conceptually and physically. The students were revolting over reading it, but she did not give up on us. She would read it to us in class, breaking it down paragraph by paragraph. Slowly, very slowly, it started to make sense, and years later, when I went back to UCLA, I was finally ready for it.

Now, I ask my students to read stuff that they don’t want to read, that they don’t understand, and I know there’s a lot of pedagogical theory about really teaching to your students and not going over their heads. But that’s a short-term way of teaching. I’m offering these texts, even if they’re not ready. I want to make them aware so it’s there when they are ready. I learned that from Minh-ha. It’s a long vision of teaching instead of the instant-result mode.

Rob Sabal on Chuck Kleinhans

Filmmaker and producer Rob Sabal is Dean of the School of the Arts and teaches in the Department of Visual & Media Arts at Emerson College and recalls classes with Chuck Kleinhans in the department of radio, television and film at Northwestern University.

Chuck Kleinhans, the publisher of Jump Cut, was a faculty member in the film program at Northwestern. What I loved about Chuck was that he tested people’s motivations. Some people blanched at that. He asked you questions: For what purpose? To what end? Who was I making films for? Why was I doing it? I have never forgotten those questions. They apply in everything! They apply in my administrative work and in my relationships. How is this helping? How is this supporting people? Is this for social justice? Is it just for me? What am I hoping to achieve? Is it to entertain? To change people’s minds? Is it to work with communities? That kind of questioning became a critical evaluative tool for me in my filmmaking.

I started as a very formalist filmmaker, and it’s hard to answer those questions when you’re making abstract experimental films that are about nothing except abstractions. Those questions imply a social nexus, or that the work is a cultural product, and thinking of it as a cultural product leads you to consider your responsibility as a filmmaker. Chuck and those questions helped me think about how privileged filmmakers are, and what kind of responsibility comes with that privilege, and it’s not a big step to ask, “Why do I have this privilege? Why do people who look like me have this privilege? How do I extend this privilege to others?” Chuck had this way of finding in students an opening that would then lead to a series of key questions that became lifelong questions. I loved Chuck.

Candace Reckinger on Shirley Clarke

Artist–director Candace Reckinger teaches in the division of animation and digital arts in the School of Cinematic Arts at the University of Southern California, where she also oversees the immersive media lab. She earned an MFA from the School of Theater, Film and Television, and recalls her mentor at UCLA, Shirley Clarke.

I remember walking into a party soon after I got to UCLA, and someone said, “That’s Shirley Clarke.” I couldn’t believe it, but there she was. I had seen her film Bridges-Go-Round, but I knew her more as a figure, a female independent director. When I met her that night, she had grey streaks in her black hair and a very New York feel. She had a lot of charisma and was smart, savvy, stylish. I took her experimental television studio class, then became her student assistant (SA) and then cotaught a class in short film design with her. A lot of the art kids were around her and went through that class. She was known as someone who would support artistic, experimental work.

Shirley had an intense personality and was very mercurial. She wasn’t an academic at all, and her classes were chaotic. She really was an artist and very quirky. She put me on camera for a dance film project with her, and she was really supportive when not many people supported women filmmakers.

People would come and visit Shirley—Nam June Paik visited, and he was such a pivotal figure then, and a couple of members of The Doors dropped by. Shirley had lived in the Chelsea Hotel for 25 years and was really lost in Los Angeles. She would go to Schwab’s drugstore, the diner where all these New Yorkers would go.

She gave me interesting advice when I graduated: She told me that I would have the same problems that she had had in her career, not because I’m a woman but because my work is in between experimental film and the Hollywood world. She said I should marry a rich man. Her advice was right in some ways—but I thought that it was very Shirley. She said it in a tough but whimsical manner.

I really liked that Shirley embraced new technology. She had a lot of status as an independent filmmaker, but she also embraced television. She may have been driven by economic reasons, but she was super excited about trying new things, and as a result, the TV studio was really fun. We had a switcher board that did all of these effects with mattes and wipes. She embraced it all. She wasn’t one of those filmmakers who said, “If I can’t make films, I’m not interested.” She had a kind of bohemian neo-realist sensibility as well as a deep interest in both dance and design, and that interest in design was very inspiring to me. I went back last year to Bridges-Go-Round and I was surprised at how much it resembled my work on the Suzanne Vega music video for “Luka.” Shirley was an impressive, artistic woman, and that made a huge impression on me.