Back to selection

Back to selection

Capturing Social Change through Clothing: Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood Costume Designer Arianne Phillips on Dressing Quentin Tarantino’s Latest

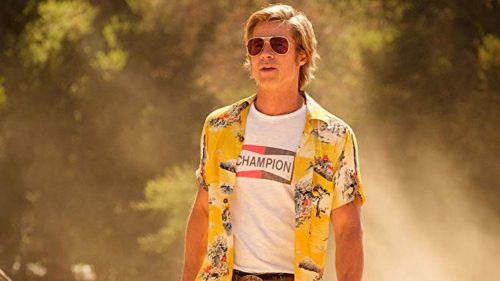

Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood (Photo: Sony Pictures)

Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood (Photo: Sony Pictures) Hawaiian shirts. Leather jackets. Go-go boots. These are just a few of the costume staples that leave a defining visual mark on Once Upon A Time … In Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino’s latest film in which real history is viewed through a fictionalized lens. We are in 1969, a year of change — both in Hollywood and the U.S. Think the start of the Nixon presidency, the eroding of the studio system before the artistically adventurous New Hollywood came to the rescue and yes, the Manson Family murders that claimed five lives, including that of a very pregnant Sharon Tate, actress and wife of director Roman Polanski.

Behind the film’s genre- and era-spanning costumes is Arianne Phillips, a singular artist and creative voice with a career in fashion and costume design that stretches over more than two decades and across music, stage and screen. Madonna’s trusted stylist and collaborator for 22 years, and a two-time Academy Award nominee (for James Mangold’s Walk the Line in 2005 and Madonna’s W.E. in 2011), Phillips brought her multifaceted expertise and extensive research to her first partnership with Tarantino, a nostalgic mélange of myth, memory and truth. “The script was so incredible in terms of Quentin’s [detailed] writing,” says Phillips by phone days before the film’s theatrical release. “It was the most wonderful opportunity I could ever be given as a costume designer. The behind-the scenes-Hollywood was rich.”

At the story’s heart is a fictional bromance between actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio), a fading star of a hit TV 1950s Western series struggling to stay afloat in changing times, and his stunt double Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt), a war hero and loyal friend locked in his own quiet battle with the industry. The duo steer their way across town as real-life figures like Bruce Lee and Steve McQueen pop in and out of the picture, the mid-’60s TV show Hullabaloo gets a brief nod and the infamous occupiers of the Spahn Ranch signpost the grim troubles ahead.

Below is our interview with Phillips, in which she breaks down her approach to the intricate period, her research process as well as a number of key costumes from the film.

Filmmaker: This film is set in the transitional year of 1969, right on the cusp of the ’70s, with lots of seismic shifts happening in Hollywood and elsewhere. I felt like you were playing with the aesthetics of both decades here, with costumes reflecting the transition.

Phillips: The center of the story is really about changing times, right? It’s about not only the culture changing — well, Hollywood is a reflection of the culture — but the whole society changing. I was a little kid in 1969, six years old, the same age as Quentin. As I read the script, the “change” part was integral to our story, and when I started my research process, it was really evident how true that was. I’ve done a few films set in the ’60s, and they’ve always been early or mid-’60s. 1969 was a conundrum for us on a daily basis. For the first time in our modern culture in the 20th century, you saw such very “dressed” [people]. And not just socio-economically, but in terms of expression. And you had the youth culture movement; it was like an incoming high tide, people were changing, people were growing their hair long. People [used to] wash and cut hair, and men put real cream and pomade in their hair. [But] as we got into the late ’60s, people were not setting their hair; they had natural hair and everything. At that time, there were [still] strict dress codes. You had to wear shoes, you couldn’t wear jeans in restaurants and men had to wear jackets. And [then] you saw the change. I really felt that; I wanted to make sure when we were dressing even the people in the background, that we were able to show the change in Hollywood.

So it took a lot more attention to detail. I told my crew, when we’re fitting these extras, we really have to fit to their space. I wanted it to be as rich as Quentin’s script. So when we actually did these shots on Hollywood Boulevard, I wanted it to really feel like a cross section of people. Not all young people were hippies — think of Tricia Nixon and young starlets that may have been more conservative. I wanted to show the change reflected in all the people who are on screen, whether they’re speaking parts or not. And of course the [lead] characters were really richly defined. We see the way that Rick Dalton and Cliff Booth dress, as opposed to the Manson family or Sharon Tate and Roman. You have a fictional narrative set against real-life events. So, it was thoughtful and character-dependent and [about] how we would show that change.

Filmmaker: That was just evident throughout, especially, in the Playboy Mansion scene. And speaking of hippies, you seem to have avoided the stereotypical/clichéd outfits we associate with the hippy culture. Instead of layers and layers of clothing and accessories, you went for something barer: shorts, crochet tops, bare feet and so on.

Phillips: I take that as a compliment because Quentin and I really wanted it to feel real. I did so much research about the Manson family, and I really felt that when dealing with counterculture and hippies and everything, it’s important to think about the contemporary eye, the audience that’s going to be watching the film, rather than going with tie-dye or fringe or the kind of monikers of that, [which] has become retro.

It was important to me, as we already know the Manson family and [we already] know the outcome, I wanted to create costumes that were quiet, so that the audience could maybe discover more about who these individual characters were. They didn’t have a lot of money. They’re dumpster diving for food. They probably didn’t wash their clothes all the time. It’s also how they dress; they weren’t in a rock band. They were transient, basically. I don’t need to tell the audience who they are. We already come with ideas so if anything, [it was about] showing how young they were. Of course they took a really dark turn. and they were monsters, but they were also really lost young people. That was important. I wanted it to feel very “reportage.”

Filmmaker: It must have been a uniquely layered challenge, dressing also for the the films and sets within the movie. There is the era the story’s set in, and there were the Westerns you were dressing. Plus, you’re also working in both color and black and white.

Phillips: You say challenge, [but they were] opportunities. For me, it’s like being able to do multiple movies within the movie. And with [the black-and-white] Bounty Law, [we] absolutely took [color contrasts] into consideration. I wanted a lot of mid-tones on Rick Dalton’s Jake Cahill character. I made that jacket he wears in Bounty Law gray. Actually we do Cliff Booth in it, as well; in the very beginning of the movie when they’re being interviewed by the news reporter. His trousers were brown, his shirt was beige and his jacket was gray. I really wanted there to be mid-tones because the other character, Michael Madsen, he wore black and white.

Filmmaker: I want to highlight a couple of specific garments for both Rick Dalton and Cliff Booth. For Rick, there’s that really sturdy leather jacket that he wears throughout a sizeable portion of the film. Whereas Cliff, we see him in a relaxed Hawaiian shirt.

Phillips: Those were scripted. Quentin had written that Cliff Booth wore a Hawaiian shirt. Initially in the script it was written that Cliff Booth wore shorts, which is very reminiscent of a lot of guys you see on set. Their uniform is shorts and a t-shirt. But we decided [on] jeans. But the one shirt was scripted. Quentin has such a rich language in his style. I felt like when I read the script, I knew exactly who that character was. Working on film sets the past 20 years and having worked with many different men, I absolutely recognized that reading Quentin’s script.

What the Hawaiian shirt looked like in terms of color and print was something that we decided later on. I researched lots and lots of Hawaiian shirts and whether they would be [from] ’60s or ’50s, or what color [they] would be, or what the print would be. A lot of thought went into it because we eventually had to make the shirts. Quentin liked the idea of Cliff wearing the Champion Spark Plugs t-shirt, so we made those t-shirts.

One of the beauties of being a costume designer is that first fitting. Lucky for me, Quentin was in this fitting. My job leading up to that is to have multiple meetings with the director and study the script and speak with the character. By the time you get to the fitting, [you] made pieces that were specific to what we were looking for. Hunted and gathered some pieces, and then we all come together in the fitting and we decide what is best for the character. That’s what we landed on.

In terms of Rick’s leather jacket, if you think of the trajectory or the body of Quentin’s work, he’s had a lot of incredible leather jackets in his movies. I actually can’t remember off the top of my head if the leather jacket was scripted, but I believe it was. We just looked at a lot of different silhouettes. Rick Dalton wears a couple of different leather jackets in the movie, [so] it was just a matter of what feels the most like the character in the fitting room. I made some jackets and found some jackets, so it’s always just a treasure hunt of sorts. Then you figure it out together and you study them.

Filmmaker: You have a number of specific looks for Sharon Tate. The mini-skirt, black sweater and go-go boots she wears in the movie theater. There’s that long snakeskin trench coat, the yellow short set underneath that she’s wearing at the Playboy party. How did you build her wardrobe?

Phillips: Sharon Tate was incredibly well-photographed, and we had the benefit of having Sharon’s sister Debra Tate as a consultant on the film. I was also able to look at some of Sharon’s clothes that Debra [still] had. She was actually preparing for an auction when we were making this film. Quentin and I decided from research what Sharon looks would make the most sense for our movie. Proportionately everything was laid on Margot. She physically really embodied Sharon in such a great way.

It was really fun re-making The Wrecking Crew outfit. We see her when she’s rehearsing the fight scene with Bruce Lee in that flashback, so that was really fun. The snakeskin coat; we made that as well. It was inspired by an Ossie Clark snakeskin coat that Sharon famously wore to the Rosemary’s Baby premiere. The black and white outfit, Sharon wore a lot of black and white. She wore a white mini-skirt and black turtleneck in (I think) the south of France. Quentin and I particularly love that look.

So, we created some pieces from research, and then the yellow ensemble for the Playboy Mansion was a vintage ensemble designed by Ossie Clark, who was a fashion designer in the ’60s and ’70s that Sharon famously wore. He was based out of London. That wasn’t an outfit that she wore or that she owned, but it was something that I found that I had never seen anything like. I know a lot about Ossie Clark, and I thought it just had a wonderful energy for our film. It worked on Margot, and Quentin and Margot and I loved it, so it made the movie.

Filmmaker: For Sharon Tate and her looks, I somehow kept thinking about names like Jean Shrimpton and Jane Birkin, some of those icons of the era.

Phillips: Absolutely. It was such a stylish era, and Sharon was one of the most beautiful women and incredibly stylish. She and Roman lived in Europe. She actually lived in Europe as a kid. Her dad, I believe was in the military and lived in Italy, and Sharon had a great sense of style [through that]. Very sophisticated and yet she had a real sense of freedom.

One thing I learned from reading about her and also [talking to] Debra was that she loved to be different. She really had a sense of ease and freedom. She was very kind, and I thought Margot did a beautiful job of capturing her spirit; really open and funny. She was a little self-deprecating, which I found to be very charming.

Filmmaker: I love that when Rick Dalton comes back from Italy with his wife, his looks change drastically for the louder, based on his shifted status. He’s wearing those salmon-colored pants and then a striped, collared sweater. His wife has this red lace jumpsuit? All of a sudden it was like, “the ’70s arrived”.

Phillips: Yeah! The jumpsuit was vintage. It’s a piece that we found that was just so special. It looked great on Lorenza [Izzo] and made sense. It just was one of those magic moments like, “Oh, we have no contest here. This is the one.” Quentin loved it. Leo’s costume in that scene is remade with the idea in mind that he has made a little money in Italy and he’s been influenced by Italian style. We see him with the little paisley neckerchiefs. He’s a little more up to date. Whereas, when he was in LA, he was struggling to keep up with the times. He’s gone to Italy and he’s become a star again, really. It’s reflected in the way he dresses. He went from pompadours to sideburns and that Engelbert Humperdinck meets Elvis Presley hair.

Filmmaker: What were some of the places that you went to for vintage hunting?

Phillips: I got a lot of great vintage pieces from costume houses all over Los Angeles. Western Costumes, Palace Costume, these are wonderful institutions that were appropriate. It was really great to get costumes from Hollywood for our movie, for a movie about Hollywood. That was really, really important to me.

In terms of vintage clothes that I bought, I engaged vintage dealers all over the country to send me; hunt and gather. I found some great stuff at the flea markets. There are a lot of really wonderful vintage stores in Los Angeles. Got a lot of clothes for our backgrounds from “The Way We Wore,” which is a wonderful, wonderful store here in Los Angeles.

Filmmaker: I love that name.

Phillips: There are a lot of really wonderful dealers that I know from years of doing this work, and everyone kind of sends me press and sent us stuff. Got some vintage clothes from shops in London, New York, Toronto so it was really kind of, no stone left unturned.

Filmmaker: I can’t let you go without telling you how much I loved your Hitchcockian work on Nico Mulhy’s Marnie opera.

Phillips: Oh, thank you so much. I’m going to do another opera with The Met in a couple years. We’re doing an opera of The Hours. A new composition for the Michael Cunningham book.