Back to selection

Back to selection

“In a Way, It is My Most Gentle Film…”: Manfred Kirchheimer on His NYFF-Premiering Free Time

Free Time

Free Time There’s poetry in the misery of a hot New York summer day. Spike Lee found it, in 1989, with Do the Right Thing: the sun-drunk torpor, the beads of sweat gliding down bare skin. Where winter tends to drive us indoors, away from the streets, summer promotes a more collective suffering. Rear Window hits a similar note of mutual, summertime malaise. The heat forces characters to sleep on their fire escapes and keep their windows open, turning the private public. Before air conditioners, where else could you escape the heat but outside, with everyone else?

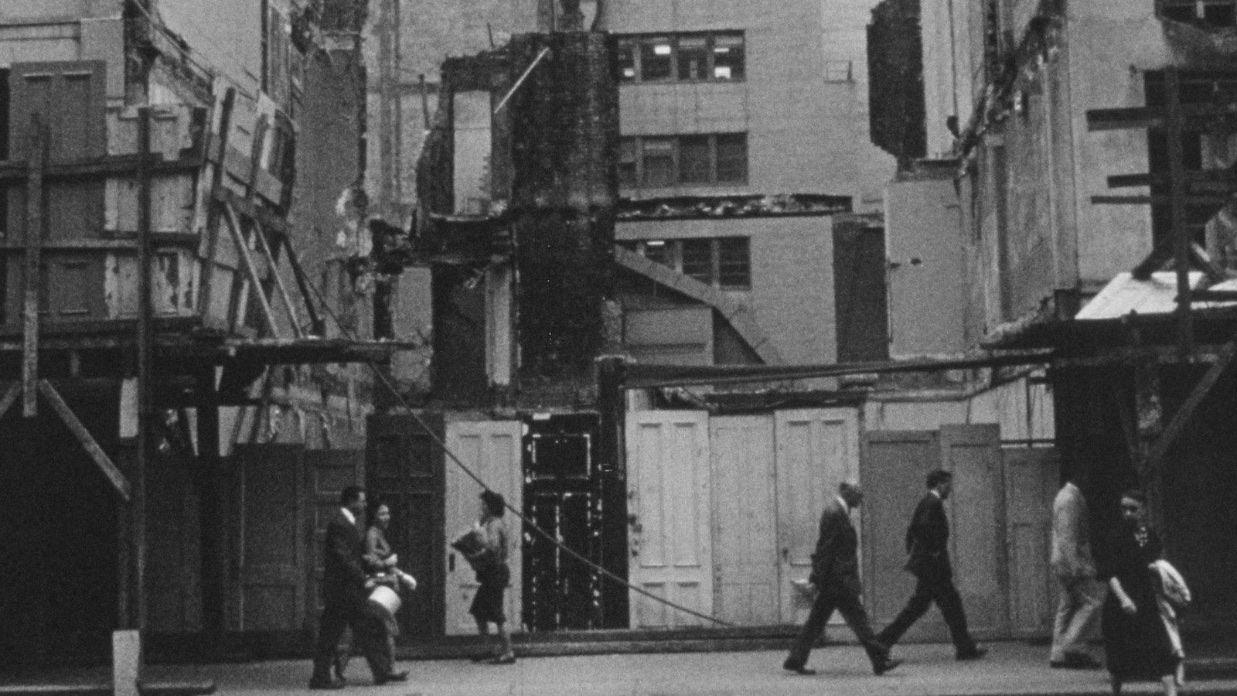

Manfred “Manny” Kirchheimer considered many potential titles for his new film, which consists of documentary footage he and friend Walter Hess shot in New York between 1958 and 1960. He settled on Free Time for this, his celebration of long, lazy summer days. One of his friends suggested an alternate title: Pre-AC. Kirchheimer shot this footage as part of a larger, never finished project with Hess on the rise of luxury buildings – what he calls “glass boxes” – in New York. The footage instead spilled across multiple documentaries over the decades: Claw (1968) and last year’s Dream of a City among them. Together, they create something of a Kirchheimer cinematic universe: abstract postcards of a mid-century New York captured on 16mm black-and-white film.

For nearly 60 years, Kirchheimer’s footage has sat in a Manhattan Mini Storage on 135th Street in Manhattan. The images are strikingly well-preserved. They show a New York not defined by ambition, hustle and bustle, or the dictates of being “crazy busy.” This is a New York of leisure and down time. Children play on the street, old men shoot the shit on lawn chairs, shirts billow in the wind on clotheslines strung between buildings. These are, quite literally, the in-between moments from his previous films, stitched together to form an uncommonly gentle portrait of New York life. You’ll find no traffic here, no subway delays, no endless construction. Free Time presents an idyllic, more neighborhood-oriented New York, one that perhaps never really existed but remains greatly alluring on the screen.

Kirchheimer, now 88, spoke with Filmmaker ahead of the film’s world premiere today at the New York Film Festival. (The film screens again tomorrow; availability is stand-by only.) Below, he shares his thoughts on the ever-changing face of New York, being compared to Jane Jacobs, and his most famous film to date, 1981’s Stations of the Elevated.

Filmmaker: So where’s this footage been for the past 60 years?

Kirchheimer: It’s been in my storage. Walter Hess and I wanted to make a rather long film about the changing city, primarily about the glass boxes that were going up and the neighborhoods that were being torn down for them. Of course that’s still going on, in Brooklyn big time. I wrote an elaborate script in which we showed the good parts of the day, and then at the end some of the neighborhoods would be torn down and glass buildings would be built.

I asked [Walter’s] permission to dig into the material on my own, and he said “OK.” I made a film called Claw at the time. From there, I used the material for three other films, the last of which was Tall. Now, with digitization, I thought I’d go back. I went back last year to make Dream of a City, which was made out of that material. And then at the beginning of this year I decided to make yet another film. I’m wondering if there’s still another film in there.

Filmmaker: What interested you in this idea of free time?

Kirchheimer: The material looked very fresh to me. Children playing in the street, which they don’t do anymore because of the cell phone. I just thought I’d play with these neighborhoods. I wasn’t thinking so much of the changing city. I had what I thought was some lovely material. It was so good looking, so I decided to go at it.

Filmmaker: Americans seem to have a complicated relationship with leisure time. There’s a sense of guilt associated with it – leisure is by definition time spent not at work. Do you think this relationship has changed from when you shot this film to now?

Kirchheimer: You know, I haven’t thought about it. Americans work harder than anyone else. They get six-week vacations in France and Germany. Americans are working all the time. The film doesn’t really show middle-aged men – working men – except in the construction sequence.

Filmmaker: The construction sequence was interesting. That was the one example where we saw people at work. I’m curious why that scene was in the film.

Kirchheimer: First of all, I had the material. It’s in the film for practical reasons. Secondly, I thought we needed a break from all the leisure time. I had to find a title that would suit everything, so I settled on Free Time at the suggestion of some of my friends.

Filmmaker: The title Free Time took my brain into all sorts of directions. I kept thinking about the classic image of New York: Busy people on a crowded street rushing to work. This film presents a different image of the city.

Kirchheimer: Yes, it does.

Filmmaker: It’s a city that hates slow walkers. Free Time is a film full of slow walkers or people just milling about. Is part of the intention here to urge viewers to slow down?

Kirchheimer: When I go to Brighton Beach, I see older people on the street in lawn chairs. I think this is a part of the city that’s not celebrated enough, but I think it exists in pockets. I don’t think the pace has gotten worse. With a number of my films, like Stations of the Elevated, people have talked about the former New York. Of course, having lived through it, I don’t see it as sharply as younger people do. I feel that New York is as comfortable as it ever was. Sure, I’m retired. I used to be part of the working crowd; I’d rush to get to my job. But I think New York is OK, today and then.

Filmmaker: The film worked on me like a piece of ambient music.

Kirchheimer: In a way, it is my most gentle film. I made a film called Canners about people who pick up cans for a nickel. That’s a rougher part of New York. Dream of a City is also a rougher part. It’s hard for me as a filmmaker to tell these things. A lot of these feelings that you’re asking about, and that I have, have happened since the film was finished. While the film was being made, I was intensely editing and I wasn’t thinking. I was surprised when people told me they liked it. Claw is my favorite film of mine, and it’s intense. It’s got a very purposeful structure.

Filmmaker: How long did the edit take?

Kirchheimer: About a half a year. I’m a one-man band. I work at home, alone. You know, I’m an old man. I find myself working fewer hours daily than I used to.

Filmmaker: What do you edit on these days?

Kirchheimer: I’m still using an old editing system: Final Cut 7, which I adore. I selected the film material I was going to use, I had to send it in for digitization and a little restoration. Please don’t say this is a restored film like all the other reviews, because it’s not. I took such good care of the material that there were very few spots on it.

Filmmaker: Unlike Stations of the Elevated, we don’t see much in the way of advertisements in this film. Was this a deliberate decision in the edit?

Kirchheimer: The billboards in Stations were meant to contrast with the graffiti. The billboards were because some Texas mogul wanted to make a cigarette commercial in New York, whereas the graffiti writers were doing their own thing and expressing themselves. I meant to contrast those two. With this project, the glass buildings represented that for me. The developers, the people who were changing the city so radically. That’s not in this film because that was in Claw.

Filmmaker: When your subjects asked you what kind of film you were making, what did you say?

Kirchheimer: I told them I was making a film about the neighborhood. The black kid and the white kid who play ball together, that was directed. The janitor who loses his broomstick, that was directed. But by and large, we shot on the fly. The lovely shot of the guy picking up the cat and his wife wagging a finger at the cat, that was all real stuff. I wish I could find those kids today. They’re 65 years old now.

Filmmaker: It’s possible one of them could see the film at New York Film Festival and say, “Holy shit, that’s me as a kid.”

Kirchheimer: Wouldn’t that be wonderful?

Filmmaker: MoMA had a retrospective of your films in 2017. The program notes compared you to Jane Jacobs as a chronicler of city life.

Kirchheimer: Oh, boy.

Filmmaker: Do you see that comparison?

Kirchheimer: I don’t quite see it. Jane Jacobs was someone who promoted neighborhoods because that was the essence of the city. She was also fighting, as I was, against these intimidating new buildings. In that sense, we were the same. I was on film, and she was writing. In addition to the writing, though, she was an activist, and unfortunately I wasn’t. I thought my films could do it all. I’d love to be paired with her, but I think it would be immodest of me to do that.

Filmmaker: I’m reminded of those New York Times articles about how certain famous people spend their leisure time. How do you spend your Sundays?

Kirchheimer: I don’t make a distinction. At a certain point, I was 30 or something, my wife and decided not to make a distinction with the weekend. We worked. She’s a writer, and I was an independent filmmaker. We worked in between industry jobs and while I was a teacher.

Filmmaker: Of course everyone talks about how New York has changed over the decades. What are some of the changes you’ve most noticed, good or bad?

Kirchheimer: The air quality has improved, no question about it. There are far more trees now; there weren’t any trees then. You don’t see any in Free Time.

Filmmaker: You really don’t.

Kirchheimer: The traffic has gotten much, much worse. They haven’t stopped building those buildings. My studio had this terrific view of the river, all the way to Staten Island. That’s been blocked now by two buildings. Now that’s happening in a terrible way in Brooklyn. Many large buildings have gone up. That trend never stopped, except during the recession. I’m always glad during a recession because there’s no building going on. [laughs]