Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“This Little Live Show I was Doing on the Board”: DP Larry Sher on Joker

Joaquin Phoenix in Joker

Joaquin Phoenix in Joker The Gotham City of Joker is a mere fraction of a degree removed from the New York City of 1981, a time and place Larry Sher knows well. The Hangover and Godzilla: King of the Monsters cinematographer grew up in nearby Teaneck, New Jersey and would sneak into the city on the bus as a teenager in the early 1980s. Sher channeled those experiences—as well as the seminal New York films of the era—to evoke the alienating urban nightmare of Gotham.

“My approach for Joker was to feed a little bit off of what the city looked like in my memory. Certainly the movies of that time fed into that as well because they were so formative when I really started studying film,” said Sher.

Also looming large in Sher’s education was a Nikon camera bestowed on him by his father, a photographic artifact that served as the jumping off point for our conversation.

Filmmaker: Tell me about this Nikon that your dad gave you growing up.

Sher: It’s a 1967 or 1968 Nikon F, and it was a large part of my own personal education in photography. When I first moved to Los Angeles I was an economics major. I decided in my junior and senior years to really pursue filmmaking and that reawoke the photography bug in me. Back then, you could actually put the Kodak emulsion from a motion picture camera into that Nikon. There was a lab back in the day in Los Angeles on Highland called RBG that had a motion picture bath [to develop the film] instead of a traditional stills bath. So I could take every emulsion that Kodak made, or even Fuji or Agfa, go out on the streets and basically shoot test rolls to learn about exposure and lighting. I took that camera with me to scout Joker, because when we started prep we were going to shoot film. Right when I landed in New York I even went to B&H and bought a really fast new 50mm prime lens for that camera, but then we decided to shoot the movie [digitally] at the last second.

Filmmaker: When you were doing those tests to first learn your craft, would you go as far as putting the shutter at 1/50th to replicate the typical shutter speed of a motion picture camera?

Sher: That’s exactly right. I took the battery out of the internal meter, which wasn’t a great one, so I’d always have to carry a light meter. If I didn’t have my light meter with me, I would guess based on my experiences up to that point. I was trying to learn about exposure and see how far over and under I could go. If I went two stops under on a day exterior that was backlit, was that to my aesthetic, or was it one stop under? How far could I get before it was too far? It was really a great way to learn. I carried that camera with me everywhere and took thousands of stills. I still have binders of them. In a weird way it informed a lot of my aesthetic, which is sort of an enhanced realism.

Filmmaker: The movie is set in 1981 in a very New York-esque Gotham City. That seems like an era when you would’ve probably been venturing into the city, since you grew up nearby in New Jersey.

Sher: Yeah, I was. I used to sneak in on the bus. I got robbed in Times Square when I was 13 in 1983. I used to describe it as a slow motion robbery. (laughs) Me and my brother and a couple friends went into the city to buy fake IDs. We didn’t really know we were getting robbed until it was over. A bunch of guys surrounded us and asked if we wanted fake IDs and we said “Yeah, how much?” They said “Well, how much you got in your pocket?” They kept taking more and more money until we were completely flushed out. Then they walked away. And we were like, “Well, at least we’re getting fake IDs.” Ten minutes passed. Then a half an hour passed. And finally we were like “Oh no, we just got robbed.” (laughs) I remember we went to these police officers on the corner, as these 13-year-old kids, and said “Hey, man, we got robbed. Can you do something about it?” They were like “There’s a bus station. Go back home to Jersey.”

Filmmaker: You also feel the influence of the New York-set films of that period on Joker.

Sher: A lot of those films were character studies that focused on one or two characters, and one of the things that was so fun about approaching Joker was that we were really servicing one character. Every scene we’re in, Arthur (Joaquin Phoenix) is our conduit to that scene. That was fun because, from a visual standpoint, you have to figure out how to emotionally connect to that character via the lens position or the lighting. Early in the movie we wanted really wide shots where Arthur is tiny in the frame, so insignificant he’s almost invisible, then to mix those with very severe close-ups. We wanted to counter those two visual thoughts in the same scene. There was a real intent to try to jam Arthur in between things and make his world feel a little bit claustrophobic, even when he’s surrounded by people. Later in the movie, as he’s transitioning, there’s an emphasis on shots that [feature him] singularly to give some of that power back to him in the frame.

Filmmaker: How close to day one of the shoot did you decide to switch over to digital?

Sher: It was the last possible minute before it was going to cost a crapload of money to switch everything over—I want to say maybe two weeks out from shooting. I think as [director] Todd Phillips started realizing the flexibility and the freedom we wanted to have with the camera, and how that would relate to the freedom and flexibility Joaquin wanted to have for his performance, that’s when Todd said “Let’s consider (digital).”

The main reason we went digital is that we really loved the idea of shooting large format. When Todd sent me the script one of our first conversations was “Man, wouldn’t it be fun to shoot this movie on 65mm film?” Because [65mm film] cameras are really hard to find and it was a little more expensive, we were dissuaded from going down that road. So we went with the idea of shooting on 35mm [film]. The prospect of shooting Arri 65 digital allowed us to go back to that original intent of large format. Todd said, “Let’s take the 35mm [film] camera, let’s take an Arri 65, and let’s go out on the streets in some of the environments that we’re going to shoot in and see them side by side.” It was really close. I remember sitting in a projection booth at Company 3 in New York and watching the film and the digital. It was just me, Todd and [Joker screenwriter] Scott Silver and you could make arguments for both formats.

There are some technical aspects to digital that really helped in a movie like this. We knew that we’d be shooting a fair amount of it really loosely, and we wouldn’t be having rehearsals or putting marks on the floor, and digital would allow our focus pullers to pull off monitors with a really high quality image. We would never have something critically out of focus or some technical problem we wouldn’t know about immediately. We had an amazing team that probably would’ve done great if it was on film, but there still would’ve been those handful of takes where there was a section of it that was more out of focus than was useable. We knew capturing Joaquin’s performance was often going to be done in one or two takes, and I think that combination of factors allowed Todd to consider digital.

Filmmaker: You’ve been a pretty loyal user of the Panavision Primos for a while, but you went over to the Arri Prime DNA lenses for Joker.

Sher: Frankly, a little bit of it had to do with money. Joker feels very uncompromised to me artistically, but on every movie— and this even goes for $200 million movies—there are all kinds of forces that make decisions for you. When I shot Godzilla: King of the Monsters, we shot Arri 65—which you can only rent from Arri, you can’t buy them—and used Panavision glass, because we were shooting anamorphic and those old C and E Series lenses are so wonderful. But that was a $180 million movie and Joker is a $55 million movie. Even though that’s a lot of money to a lot of people reading this article )and it is to me too), the difference mattered. Trying to make a deal to mix and match Panavision and Arri—because they both have vested interests in making money on the rental—pushed the decision toward using Arri glass. We ultimately ended up using a combination of different lenses: four DNA focal lengths, then a bunch of other lenses that would cover the large format.

I was looking for three things when I tested lenses. First, I didn’t want anything super sharp. I wanted the feel of older glass. Second, I needed faster lenses because I was going to be shooting in very low light conditions. And third, I needed lenses that could do close focus, because we were going to be shooting these tight close-ups of Joaquin and I wanted to be able to get quite physically close to him with the camera. Those criteria basically drove my lens set.

Filmmaker: Aren’t only a few of the DNAs faster than a T2?

Sher: Yes, the 80mm DNA is a T1.9 and that’s an awesome lens. I also ended up with six lenses from this company Cinoflex that rehouses old glass to make them closer focus and faster.

We carried two 35mm lenses. One had better optics and one was faster. I carried two 50mm lenses for a similar reason—one was faster and the other was closer focus. Then I carried a 58mm [Nikon] T1.3, which was awesome and a real hero lens that we’d shoot like crazy. We also had a beautiful 135mm Canon and this amazing 280mm Leica that was gorgeous. There’s a close-up of Joaquin at the end of the movie where he starts singing. The frame is like eyes to mouth and he’s just kind of staring into the lens. That’s on a 350mm lens at close-focus at right about eight feet. That’s one of my favorite close-ups of the movie. You usually take out maybe 10 or 12 lenses, but you really only end up mainly using four or five hero lenses.

Filmmaker: I really love the shot of Joaquin in the back of the police car as it drives by the rioting clowns on the streets of Gotham.

Sher: That shot is meant to mimic the shot of him riding on the bus in the beginning of the movie. It’s almost the exact same position and size. We shot that on the 58mm lens. That scene was part of night shooting we did in Jersey. We wanted to mimic the lighting of what was going on out the window—which was like fire and all this activity he’s supposed to be looking at—but we hadn’t shot [those reverses yet] when we did Joaquin’s shot, so we came up with a solution. You know those big TV screens they put on the back of trucks as advertisements? I called up one of those guys and asked, “Can you put whatever media you want into it?” So I cut together a bunch of riot footage that had fire in it and fed that into one of those LED screens. That truck drove next to the cop car with Joaquin in it to help provide interactive lighting on his face.

In the movie he leans in to the window, then he leans into the metal divider between him and the cops and goes “Isn’t it beautiful?” Then they get hit by a car. We did [the shots of him in the police car before the crash] with two cameras. I had another camera car to the left that also had a bunch of moving lights on it to mimic what Joaquin sees out the window, but it also had an electrician who could do the headlight [effect for the vehicle that crashes into the cop car] on cue. The second camera was sitting in between the seats, so when Joaquin leans in we could capture it all at once. So the ad truck was on one side of the car, then this other insert car with lighting on it was on the other side, so we could drive in real time like a three car armada.

We ran the route [once] and Todd said “Let’s just do this on stage.” I said “Let’s do it again. We’ll get it. It’s really beautiful.” And he was like “Yeah, I know, but I think we’ll just have more control if we do it on stage,” because we already had to do [other shots from that sequence] on stage anyway. But the shots that are in the movie are mainly from that first take we did on the actual street.

Filmmaker: Another of my favorite shots comes in the Murray Franklin dressing room right before Arthur goes on Franklin’s talk show. The camera is behind Joaquin and he leans backward in a chair with a cigarette in his mouth and puts his feet up in soft focus in the background.

Sher: That is an example of what was thrilling about making this movie. Todd loves to roll before we yell action and he loves to keep rolling after we call cut. On Joker sometimes we’d just keep rolling and it would go on and on until either Todd or Joaquin got bored, then we would finally cut the camera. For that scene we had two handheld cameras in the room basically shooting the wider shot over Joaquin as he talks to Murray Franklin. Then we just kept rolling afterward and that shot was the A-camera operator Geoff Haley keeping it going as Joaquin sat in a chair in front of us and leaned back. So that shot, which is wonderful, was just found on the day.

Filmmaker: That’s all I’ve got on my list of questions. Is there anything that you haven’t been asked about yet when you’ve been doing press that you were hoping to get to talk about? Any particularly challenging scenes to pull off?

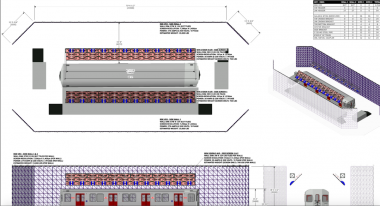

Sher: The subway killing was one of the most challenging sets in the movie. That whole scene was shot with LED screens outside [the subway car’s windows]. It was a really technical endeavor in conjunction with the visual effects team and my gaffer, Steve Ramsey.

There are a couple of possible solutions for how to get what you need outside the windows. One is to find a dead track and shoot on an actual train car. We did that a little bit for the scene where Arthur is escaping the cops and all the guys on the train are in clown masks. But shooting on a real track—besides all the resets—usually means you’re going to have to rush and shoot it with more compromise and you’re going to be in an environment that is less controlled.

Once you decide to shoot on stage, you have three options. You can just put black out there, but then you don’t really feel like you’re moving through different environments. Another option is you can put bluescreen or greenscreen out there and put in plates later, but that’s going to compromise where you can put lighting. The solution that we came up with was to do it with LED screens, though the additional cost from going that way meant we had to cut a day of shooting just to pay for it. So we put LED screens out there and not only can you photograph those screens and the media on them, but they also provide interactive lighting.

However, we still had to find a way to get the plates [to play on those LED screens]. Because of Homeland Security, you can’t actually put cameras on the outside of trains anymore to shoot traditional plates. So the VFX supervisor, Edwin Rivera, and I would ride the subways at night taking pictures and video to try and figure out a solution to get plates. What we came up with was, we actually shot stills. We went into the subway stations and we literally would stand there and take a frame and then walk one step to our left (and take another frame) until we’d created these massive panoramas.

Film is 24 still frames a second, which goes back to what we were originally talking about how I got started in cinematography with stills. Here, we were using the essence of filmmaking to create these interactive images outside the window. So, when the car pulls up to the station and that woman gets off and Arthur is sitting by himself and then we take off from the station again—that’s all stills out the window in a huge timeline, so that we can then ramp up the speed of the stills to [create the illusion of the subway car changing speeds]. I could sit at a board with a monitor and literally, in real time, hit a button and all the lights would go off inside and a subway station would pass by the windows. Then I could hit another button and we would pass a bunch of white light. Hit another button and we’d pass a bunch of tungsten light. It was like this little live show I was doing on the board. I’m super happy with the way it came out. There are certain scenes in a movie that become a conversation that you’re having every day to try to figure them out. That was one of those scenes.

Matt Mulcahey works as a DIT in the Midwest. He also writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.