Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance 2020 Dispatch 8: Time, The Nest

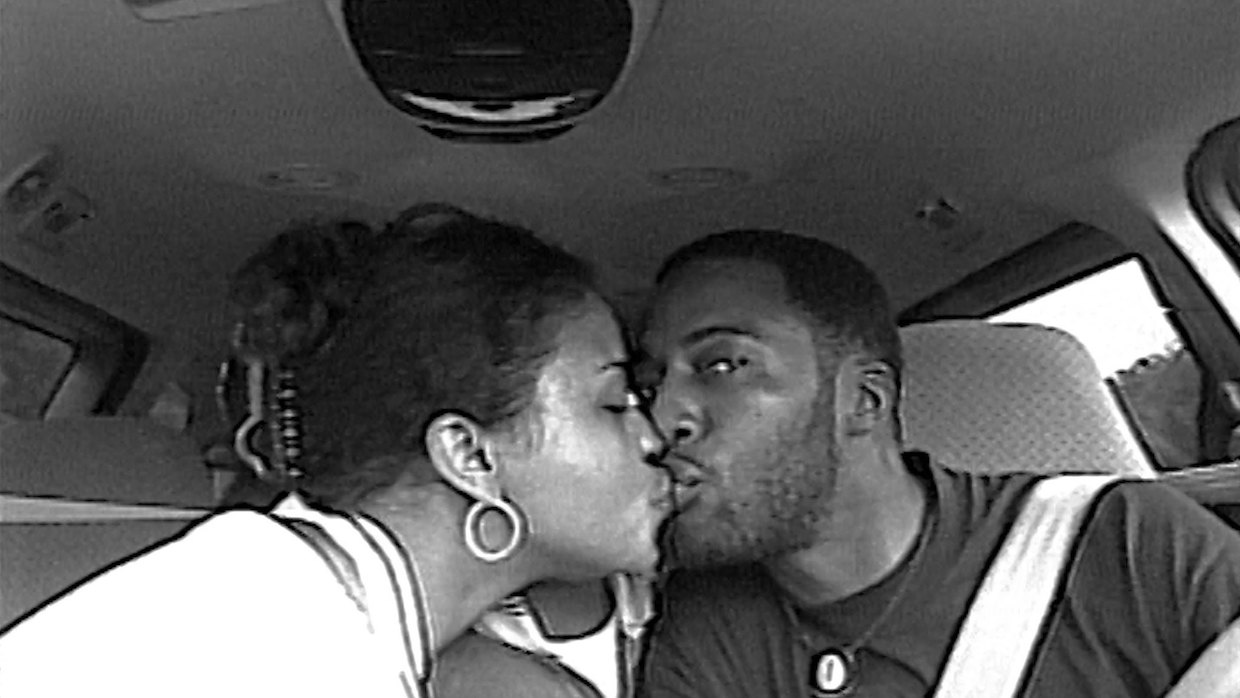

Fox and Rob Rich in Time (Courtesy of Sundance Institute)

Fox and Rob Rich in Time (Courtesy of Sundance Institute) In 1999, Fox and Rob Rich, desperate to shore up the finances of their business (Shreveport’s first urban clothing store) robbed a bank; she got 12 years, he got 60. The throughline of Garrett Bradley’s Time—a compact epic spanning 21 years in 87 minutes—tracks Fox’s ceaseless efforts to get her husband home. Her website describes her as a “realist speaker”: a motivational lecturer transmuting her difficult experiences for higher ends than the usual conference room guest, as well as a “prospective Nobel Peace Prize winner” who “is both a teacher and servant, entrepreneur, business owner and most of all a humanitarian.” This is a firmly controlled/messaged self-narrative, one Bradley allows room for: we see Fox in action, both in a single presentation (at Tulane University) the film repeatedly returns to, and in a montage of similar speaking dates across the country.

But Time isn’t a supplement to a speaking tour, and (at the risk of sounding exceptionally cold-blooded) that it’s “powerful” isn’t necessarily its most important attribute. “Powerful” is, on some level, easy, because this is a film about a monstrous system, but Time is also interesting, and its title indicates why. Bradley begins, more or less, at the beginning: a much younger Fox not just live-blogging but VHS-blogging, with tracking lines at screen bottom, pregnant with twins conceived before her husband went to jail. The outlines of courtship, marriage and attempt to launch a career are verbally recapped, but not smoothly or all at once. All footage is heterogeneously sourced black-and-white: the lowest-res from the family archives, the highest-res and most recent in gleaming B&W, drone shots and all. No direct chronological markers are provided onscreen, and it takes a while to catch on to how time loops around in this narrative construction.

The musical soundtrack is primarily (excellent) Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou solo jazz piano recordings, allowed to stretch out in full for surprisingly long stretches, establishing a contemplative POV/tonal counterpoint outside the family’s immediate experience. The voiceover testimony isn’t univocally Fox’s but opened up to other members of the family musing on Time, the abstract concept: what you make of it, an unbiased force etc. These are less interesting in and of themselves than as examples how people dealing with a concrete carceral situation find themselves, while waiting for something to happen, killing time by abstracting and extrapolating their experience beyond the personal or even systemic, if only as a coping mechanism. While Bradley’s leaping around past and present, she anchors the narrative by repeatedly coming back to Fox on the phone, calling every office she can for an update that doesn’t seem to ever be forthcoming—her being on hold for a very long stretch is a leap back from abstraction to sheer present-tense endurance. The final chronological leap the film makes—rewinding much of what we’ve seen backwards—conveys an impossible longing to go back and undo a single moment, mentally reliving everything that came before.

Nine years after his feature debut, Martha Marcy May Marlene, and one BBC mini-series later, Sean Durkin’s sophomore feature The Nest wore me down. It’s May 1986, a moment time-stamped by background radio news announcing the Reagan administration’s imposition of trade war-motivated quotas on European chocolate and white wine. The resonance with our stupid present (POTUS, 3/2/18: “When a country (USA) is losing many billions of dollars on trade with virtually every country it does business with, trade wars are good, and easy to win”) continues throughout this story of an aspirational yuppie huckster on the failed make. With his American business revenue drying up, British finance bro Rory (Jude Law) moves his American wife Allison (Carrie Coon) and their two kids (one hers from a previous relationship, the other from their marriage) back home, where he preaches the virtues of privatization and deregulation. Setting aside the macroeconomic implications of his beliefs, it emerges that Rory isn’t particularly adept at worsening the the world for financial gain—his glad-handing is too transparently substanceless, a walking manifestation of Blur’s “Charmless Man.”

Jude Law has long been great at leaning into active self-loathing onscreen (cf. A.I., I Heart Huckabees) and is totally on-point—the entire cast is sharp, the film recognizable as formally following up where Martha left out, deploying a characteristic slow zoom-out almost immediately. I can’t improve on Noel Murray’s succinct description of how it operates visually: “a domestic melodrama shaped as a spook-show.” The gigantic mansion Rory moves his family into (Led Zeppelin used to live there, he says of the space, which looks exactly right for some Black Magick dabbling) is full of sinister visual possibilities, which Durkin and DP Mátyás Erdély light for maximum creep factor. But this isn’t a genre bait-and-switch but a surprisingly plodding, didactic narrative in which a man who’s lost his financial soul also alienates his entire family to bring the message home.

There are three or four terrific scenes, primarily of meanly articulate arguments between Rory and Allison, in which the film springs to life, but they’re anomalies in an on-task, ultimately pretty simplistic narrative. Not uniformly, since grace notes are scattered throughout: a friend told me during the festival that for British people, American English is bizarre because of its use of older words that have long been replaced by newer ones on the island, which explains a pretty funny joke where Rory sneeringly explains that in New York, “autumn” is referred to as “fall.” But more representative is the metaphorical horse which mirrors the marriage’s slow dissolution: it’s transported across the ocean, grows restless, then falls sick, etc. Not a single person I talked to about the film could avoid describing this as, both metaphorically and eventually literally, the narrative flogging of a dead horse.