Back to selection

Back to selection

Maniac, Flashdance and Fatal Attraction: Jim Hemphill’s Home Video Picks

Maniac

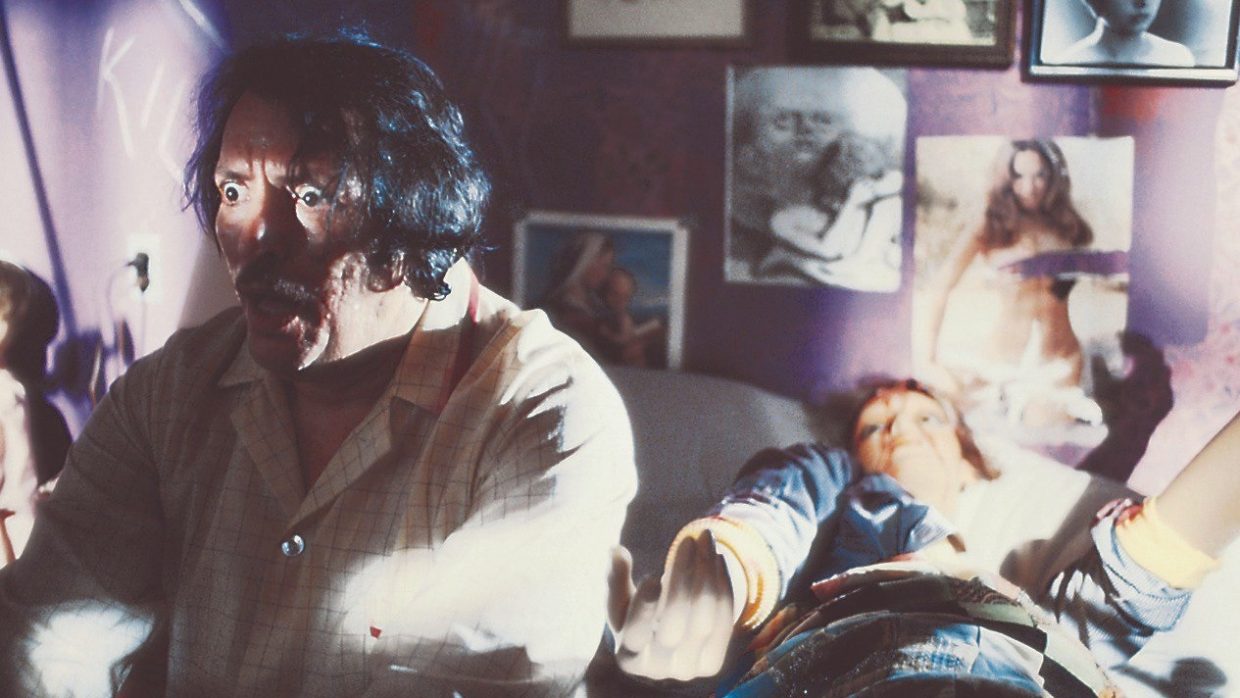

Maniac In late 1979, Joe Spinell was a successful character actor who had appeared in major films by Coppola, Friedkin, Scorsese and Mazursky, but he wanted to go beyond supporting work to make a name for himself as a horror icon. His friend William Lustig was a 24-year old movie fanatic who had directed a couple of adult films and was hungry to graduate to mainstream features. Joining forces with producer Andrew Garroni, Lustig and Spinell scraped together $48,000 and started making Maniac, an extremely unpleasant – and extremely effective – study of a psychotic loner on a killing spree. They never really had a budget, just a general policy of making the movie for as little as they could, and they kept production going thanks to luck, favors, and a shockingly generous bank that gave Lustig an unsecured $10,000 loan at a moment when he was down to his last 20 bucks. Ultimately, their low-budget passion project grossed millions of dollars, launched Lustig’s directing career, and attracted the ire of film critics like Gene Siskel, whose outrage over the film’s violence generated mountains of free publicity. Viewed today, almost 40 years after its initial 1981 release in U.S. theatres, Maniac remains shocking due to a combination of Tom Savini’s nauseatingly realistic special effects (he was coming off of his groundbreaking work on George Romero’s Dawn of the Dead and the original Friday the 13th) and Spinell’s committed and ugly performance; there’s also the fact that Lustig’s grimy vision of New York is so drenched in sleaze and alienation that it makes Taxi Driver look like The Princess Diaries. It’s here that the low budget works to Maniac’s benefit; since there was no money and the whole thing was shot on location (often without permits), Maniac has a sense of documentary authenticity and historical value that many bigger budgeted films of the era lack.

Lustig delves into his guerilla approach and the state of exploitation filmmaking at the time on the many hours of special features included on Blue Underground’s extraordinary new 4K edition of Maniac, which is quite simply one of the best overall home video packages I’ve ever come across. There are two fantastic commentary tracks in which Lustig and his collaborators share informative and often hilarious stories from the trenches of independent filmmaking, and then there are hours upon hours of interviews with virtually every important participant from the time of the picture’s release as well as later conversations recorded over the course of the four decades that have followed. There are also publicity materials and local news reports from 1981 that provide a comprehensive view of the controversy that Maniac both suffered and benefited from, and a promo reel Spinell made for a never-produced sequel. Cumulatively, these supplements provide a fascinating portrait not only of Maniac but of an entire era of independent genre film production and exhibition – I’ve rarely felt so satisfied by a disc’s extra features, to the point that the disc is worth picking up regardless of how you feel about the movie itself. Blue Underground has also released a new 4K edition of Lucio Fulci’s grindhouse classic Zombie that’s similarly generous with its supplemental materials; I don’t have space for a full length review, so if you’re not familiar with Zombie I’ll just report that a zombie fighting a shark is only one of its many pleasures. If you’re not the kind of person who considers such a scene a viable reason for watching a movie, Zombie probably isn’t for you. If you are that kind of person, it’s a must-see.

For those whose tastes in ’80s cinema tend toward the more polished and mainstream, two films by one of the decade’s most accomplished visual stylists are newly available in gorgeous upgrades. First up is Flashdance (1983), a dubious studio assignment elevated to the level of high pop art by director Adrian Lyne. The premise is an R-rated twist on conventions familiar from the days of Mickey Rooney and Busby Berkeley: Alex (Jennifer Beals) is a Pittsburgh welder by day and “flashdancer” by night who dreams of going to a prestigious performing arts school and becoming a professional dancer. In the world of this movie, flashdancing is a kind of desexualized hybrid of stripping and performance art in which Alex and her colleagues put on elaborate shows with masks, costumes, and lighting effects in a bar whose clientele looks like they wandered in from a truck stop. I’m not sure who the real audience for this kind of dancing would be, or if the women could really give such artsy performances to a group of rowdy, horny guys without being booed off the stage, but I’ll take screenwriter Joe Eszterhas’s word for it that bars like the one in Flashdance really existed in the period when the film was made. I’ve believed weirder things in movies, I suppose.

Anyway, Alex falls in love with her rich boss Nick (Michael Nouri), and in between welding, pseudo-stripping, and torturing Nick’s ex-wife, she pursues her dream of becoming a professional dancer. That’s about it as far as plot goes, but Flashdance isn’t a movie about plot – the story is primarily a thread to hang a bunch of stunning visual and aural set pieces on. Lyne came to Flashdance from an advertising background (though he did have Foxes under his belt), and he basically extends the precision and flair he would ordinarily apply to a 30-second TV spot to a feature-length film. Lyne takes scenes that other directors would slough off as filler, like the inevitable “falling in love” montage between Beals and Nouri, and shoots them as meticulously as the ballet in An American in Paris. It’s an appropriate approach, given that in a way Flashdance is nothing but filler – it’s less a movie than a 90-minute commercial for a soundtrack. Yet on its own terms it’s a nearly perfect movie, thanks to Lyne’s exquisite sense of craft as well as his eye for young talent. As Alex, Beals is natural and charming; it’s easy to see why a nation of young women related to her and made the movie a hit. And the perennially underrated Nouri is great in what could have been a thankless role; his part is more of a dramatic device and a symbol than a character, but Nouri commits to the performance and gives Nick an authenticity and emotional weight that make the flimsy love story totally convincing. While Lyne always got a lot of attention for his visuals, he’s grossly underrated as a director of actors; the performances in his two subsequent films, 9½ Weeks and Fatal Attraction, are extraordinary, and Flashdance is filled with colorful supporting turns from the likes of Kyle T. Heffner, Lee Ving and Cynthia Rhodes. Both Flashdance and Fatal Attraction have been remastered for new Blu-ray editions that contain extras from previous DVD releases as well as brand new interviews with Lyne; the supplements are terrific, the director-approved transfers even better.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.