Back to selection

Back to selection

“No Talking Heads on Camera”: Sam Pollard on MLK/FBI

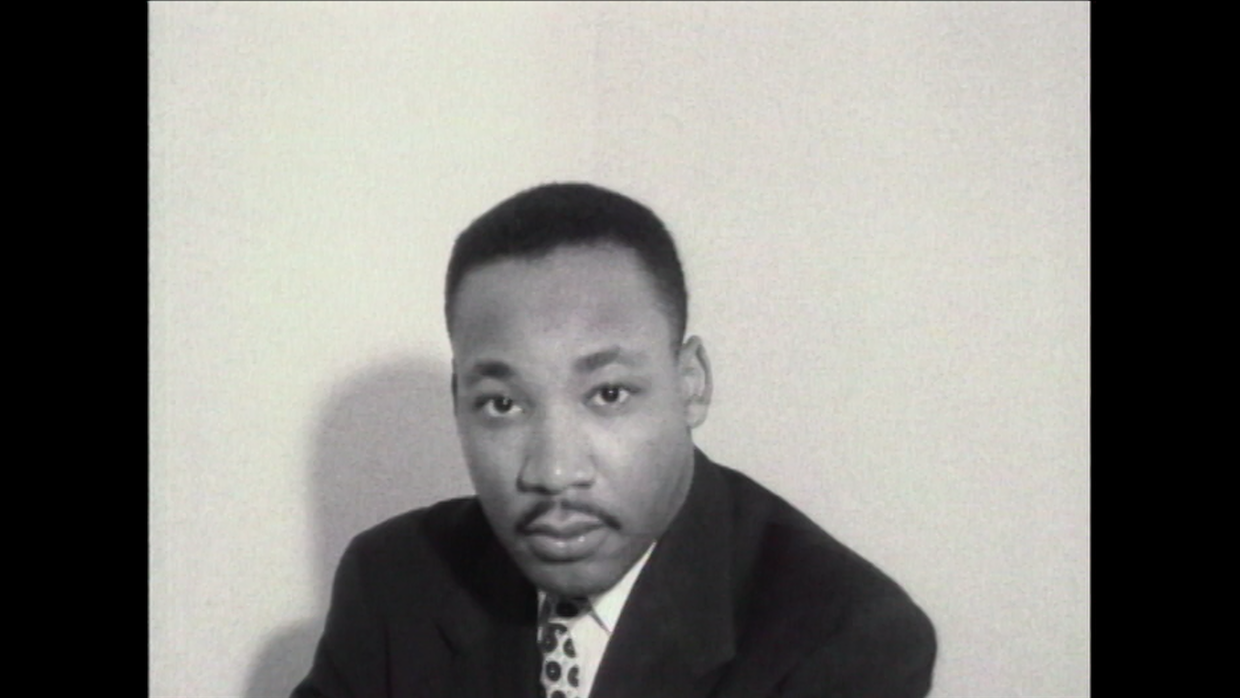

MLK/FBI (image courtesy of NBC)

MLK/FBI (image courtesy of NBC) In 1963, the FBI under J. Edgar Hoover began wiretapping Martin Luther King, Jr. with the goal of undermining his authority as a civil rights leader. Utilizing a wealth of newly discovered and declassified files obtained through the Freedom of Information Act, as well as newly restored footage from the period, MLK/FBI delves into the Bureau’s deeply questionable methods and motives for surveillance, while painting a portrait of King that does not shy away from uncomfortable truths.

Directed by Sam Pollard, best known as Spike Lee’s editor on films like Clockers and Bamboozled, MLK/FBI builds upon a lifetime of work committed to exploring the history of American race relations. Consider Pollard’s multiple writing, directing, and producing credits on the epic documentary series about the civil rights movement, Eyes on the Prize (1986), to his more recent films about the lives of Zora Neale Hurston, Sammy Davis, Jr. and August Wilson. In MLK/FBI, Pollard examines how the Bureau worked to manipulate public perception of Dr. King, hoping that revelations about his private life, and his non-monogamous marriage, would neutralize his influence. The tactic spoke directly to white America’s anxieties around Black empowerment. American culture and the movies reinforced this fear through the depiction of Black male sexuality as a nefarious, deviant force. Pollard compellingly demonstrates how the economy of images in American popular culture have historically upheld standards of white supremacy, and how these texts helped construct narratives about Dr. King’s treachery and the FBI’s righteousness.

Ultimately, the film articulates how Dr. King and the FBI represented two distinct versions of the American dream; one that aspires for more, the other desperate to protect what it already has. But rather than rehash a David and Goliath story about one man’s battle against a rogue entity, Pollard privileges the “shades of grey” that complicate, but ultimately strengthen our understanding of the civil rights leader, and the agency’s not-so dated mission.

Between virtual screenings at the Toronto International Film Festival and the New York Film Festival, Filmmaker caught up with Pollard via video chat. The film will be released in January of 2021 by IFC Films.

Filmmaker: What were the origins of the MLK/FBI, and how’d you get involved?

Sam Pollard: Over two years ago, Benjamin Hedin, the producer of the project whom I had worked with for Two Trains Runnin’ (2016), called me. He had just finished reading David Garrow’s book and came to me saying “I think we have our next film—it’s about King being surveilled by J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI.” He sent me a copy of the book; I read it in about three or four days and called him back to tell him he was absolutely correct. So, we set forth on making a film about how [Dr. King] is considered an icon now but was considered a pariah back in the day. We put together a sizzle reel. We interviewed Dave Garrow for about four and a half hours in Pittsburgh, where he’s from. Then we pitched [the reel] to different companies, and they all turned us down. Ben was able to get another executive producer on board, David Friend. Then we got Cinetic, a company that helped raise the money, which ended up coming primarily from two companies, Field of Vision and Play Action.

We shot the rest of the interviews in the fall of 201. We started editing in late fall, early winter that year, and we had a rough cut by February or March. Then we started the editing work with Laura Tomaselli. We finished the film basically like a month ago. Two and a half years is not a long time to get the film done.

Filmmaker: Can you talk a little bit about the process of sorting through all that archival material?

Pollard: We brought in some wonderful archival producers. The main one was a gentleman named Brian Becker, who found material I had never seen before—Dr. King with his family, Dr. King giving speeches in places I had never seen. He also found footage that I had seen from working on Eyes on the Prize in places like Chicago, Birmingham and Montgomery. So, it was a combination of new and old material, and many tremendous photos of Dr. King and other members of the SCLS—Andy Young, Clarence Jones, and people involved in ancillary organizations, like Rory Wilkins or James Farmer. When you’re making documentaries, and particularly historical documentaries, you really want to make sure you leave no stone unturned. Laura Tomaselli did a tremendous job culling through all that material and finding material that helped shape the arc of the story.

Filmmaker: Then there’s the footage from old Hollywood movies.

Pollard: That was another important part of the process, finding those films about the FBI and the Communist party. We found films like John Wayne’s Big Jim McLean (1952), where he was an FBI agent trying to uncover communism; also, I Was a Communist for the FBI (1951), Walk a Crooked Mile (1948), The FBI Story (1959), starring Jimmy Stewart, and an FBI series from the ’60s with Efrem Zimbalist, Jr. So we not only found archival footage, but also movies and shows that were really touting how wonderful the FBI was.

Filmmaker: That really stood out to me, this idea that cinema itself is complicit in the oppression of Black Americans and in the romanticization of institutions like the FBI. You also include footage from Birth of a Nation (1915), which presents Black masculinity as deviant and dangerous. And the film shows how the FBI was drawing from these racist assumptions, shaped in part by cinema, in their effort to delegitimize and humiliate Dr. King.

Pollard: That’s something that’s constant in American history—the sexualization of Black men and how you have to be fearful of them. That goes all the way back to D.W. Griffith, to the silent era, and this fear of the Black man, and of Black people rising up has continued for many, many years. I grew up as a child in the ’50s and ’60s. America was basically whitebread. There were American television shows like Father Knows Best and Leave it to Beaver where families were homogenous and white. All of a sudden comes a man in 1955 who becomes the leader of this boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, and who says African Americans need their rights as well. White people were afraid of this sudden change to the status quo.

Think back to the documentary, when Dr. King is on that television show and this white journalist asks him if he thinks things are going too fast, that the movement is causing riots. We still hear that kind of language today: this fear that “things” are moving too fast, that law and order has to be in place. It’s amazingly sad.

Filmmaker: Nowadays we often, very simplistically, look back at Dr. King as this pure, perfect figure. It’s such a 180 from how he was viewed at the time. Someone like Sidney Poitier comes to mind, and this idea that in order to be accepted and legitimate as an African-American figure, you have to be seen as perfect.

Pollard: Sidney Poitier had to be perfect, he could not be a threat. I’ll give you two examples: his 1957 film Something of Value, where he’s part of the Mau Mau movement, but ultimately sacrifices himself in order to rise again. Then there’s The Defiant Ones, which he did with Tony Curtis the next year. [In that movie] he’s about to escape on a moving train, but Tony Curtis can’t barely make it. So [Poitier] sacrifices himself and becomes the symbol of the good Negro. Dr. King was a powerful speaker even though he had a calm demeanor. He was a threat because he wasn’t sacrificing himself. He was fighting for the rights of our people. That became frightening to white people, even in the north. Here was a man upending what they perceived as the social order.

Filmmaker: The film is in part about demystifying the legend of Dr. King. Is hero worship dangerous?

Pollard: Absolutely. When you elevate someone to be an icon, you forget that they’re human beings and complex. You forget that King did not do it by himself. He had lots of foot soldiers. There were other people part of the movement making things happen. The young people did the sit-ins: Bernice Regan, James Bevel, Fred Shuttlesworth, Dorothy Ide. There were so many other people part of the struggle. It wasn’t King alone. He was iconic because he was a rousing speaker, but it’s always dangerous to take someone and elevate them to that kind of status.

Filmmaker: What was your personal experience in relation to Dr. King and the FBI? How have your views changed since you were young?

Pollard: Being a documentary filmmaker—and this goes back to my time working on Eyes on the Prize—my point of view about America has become more complex. As a young man growing up in the ’60s, my household had a portrait of Dr. King and JFK on the wall. Back in 1961 or 1962 these guys could do no wrong. These were great men, and it took me a while to understand that they’re complicated human beings that have their own Achilles’ heels. I grew up in America and believed there were the good guys and the bad guys. I bought into the mythology of the FBI. J. Edgar Hoover was part of this organization called the G-Men [Government Men]. They were wiping out gangsters; they were trying to make sure Communism wasn’t going to take over the country. As a 14-year-old, I supported the war in Vietnam. I remember being in middle school arguing with some of my classmates about how important it is we save the South Vietnamese from the scourge of Communism. That’s called American brainwashing.

Filmmaker: Your career is defined in part by the documentaries you’ve made about the civil rights movement, and the lives of some of the great African American artists and figures in history. How does MLK/FBI fit within your body of work and build upon your concerns as a filmmaker?

Pollard: These works exist on a continuum. My philosophy on every film I’ve done—from Eyes on the Prize to my films on Sammy Davis, Jr. and Zora Neale Hurston—is to look at these people who are celebrated and sometimes worshipped, and see how they’re complicated, how they’re not just one thing. They all have different levels and different parts of their personality. With this film, I wanted to dig into that. I didn’t want [Dr. King and the FBI] to be presented in black and white. I want to show you the nuances of a person’s life experience, their shades of grey.

Filmmaker: There’s no talking heads until the end of the film, so the only indication of a new speaker is the sound of their voice and a caption with their name. Can you talk about the decision to have the archival footage stream uninterrupted for most of the film?

Pollard: That was something we discussed right at the beginning of the process. Do you remember the documentary, The Black Power Mixtape? When I saw that in theaters I remember there was no one on camera, just voices. I told Ben that’s what I wanted to do, and he agreed completely. Let’s make it all voices. When we pitched the idea to funders there was some reservation about no talking heads on camera, but we stuck to our guns. We didn’t want to interrupt the archival material, which is telling a story of its own. In the past I had already taken this approach when I was an editor for Alex Gibney’s film about Frank Sinatra. It’s a bit unnerving to make a film when there’s no one on camera, but I think most people will embrace it. The idea of bringing the people on camera at the end was Laura Tomaselli’s, so I tip my hat to her.

Filmmaker: At the end of the film, James Comey is interviewed and voices his regret about the agency’s past practices. At the same time, the larger conclusion the film makes about the FBI is that back in the ’60s it wasn’t some sort of rogue agency, but a legitimate arm of the entire government. Have things changed?

Pollard: Who’s the attorney general? Bill Barr. The government can in all actuality still do the same thing. They probably are. Bill Barr is pointing down to protestors and trying to connect them to Antifa, which is the new word for Communism in America. They’re saying Antifa is trying to destroy the fabric of American society, and we have to be careful, and we have to take them down. [Barr] is basically doing the same thing that Hoover did as the director of the FBI.