Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

“The Brightest Light of a Shot Doesn’t Always Have to Be on the Actor’s Face”: DP Matthew Libatique on The Prom

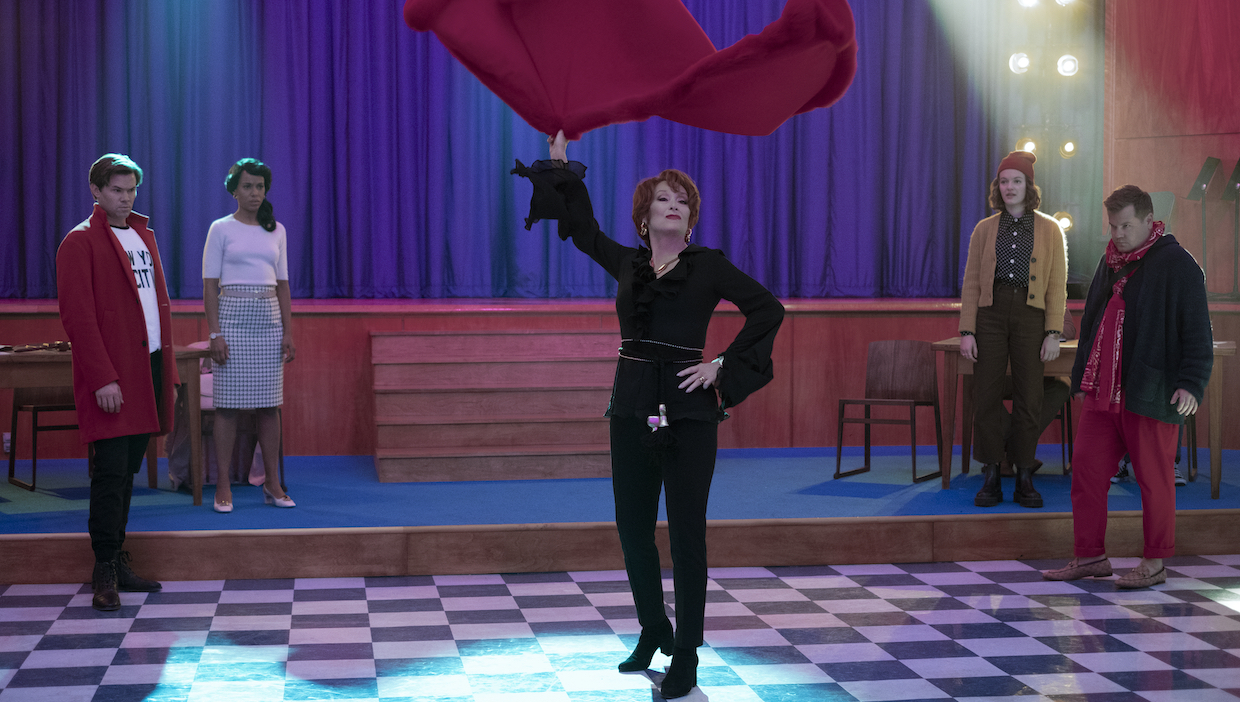

Andrew Rannells, Kerry Washington, Meryl Streep, Jo Ellen Pellman and James Corden in The Prom (Courtesy of Melinda Sue Gordon/Netflix)

Andrew Rannells, Kerry Washington, Meryl Streep, Jo Ellen Pellman and James Corden in The Prom (Courtesy of Melinda Sue Gordon/Netflix) Matthew Libatique likes to say that sometimes lighting needs to be the lead guitarist and sometimes it needs to be the drummer. The Prom is definitely a lead guitarist kind of movie.

An adaptation of the popular musical, The Prom follows four Broadway personalities (Meryl Streep, James Corden, Nicole Kidman and Andrew Rannells) hoping to boost their careers by descending on small town Indiana as “celebrity activists” in service of the cause of a gay student banned from attending the titular bash with her partner of choice. With the movie now streaming on Netflix, Libatique talked with Filmmaker about working with spherical lenses, shooting at Applebee’s, and how Excel spreadsheets are his secret weapon for controlling the chaos of a movie set.

Filmmaker: Is The Prom the first project you’ve made directly for streaming?

Libatique: Chi-Raq [for Amazon] was technically the first one produced by a streaming service, but it was still a theatrical release as well. The Prom was the first time I knew going in that it was pretty much going to be a streaming film.

Filmmaker: Did that change anything for you?

Libatique: I’m so new to the streaming platform that no, it didn’t. I just approached it the same way. I was definitely conscious of how the workflow might change based on the streaming aspect of it, but my approach was the same. I always used to say, “I shoot for the premiere.” I shoot for the best-case scenario. When we started making the film it was pre-pandemic, so I thought there would be a premiere, and that’s what I was shooting for.

Filmmaker: A lot of filmmakers seem to love working for Netflix—certainly directors of a certain stature—because there’s a degree of freedom and control returned to them. But when you’re a cinematographer, working for Netflix or the other streamers comes with certain technical parameters you have to meet.

Libatique: 4K! [laughs] The first person who raved about Netflix to me was James Ponsoldt. We did a film called The Circle together and he subsequently did some Netflix stuff and I remember him saying, “You would just love it. They’re so filmmaker friendly.” And I have to say that he was right. It was an experience that I didn’t feel restricted on.

Filmmaker: You’ve shot quite a few films on the classic Alexa and the Mini, but for The Prom you went large format with the Alexa Mini LF. Was a big part of that just the LF meeting the 4K requirement and the regular Mini not doing so?

Libatique: Yeah, absolutely. I love the Arri sensor and what it can do just right out of the box and I love the Mini, both for its form factor and its image. So I was intrigued by the Mini LF. It satisfied that 4K mandate and I was still going to be able to shoot with the sensor that I was accustomed to from the last three or four films I’d made before that, so it was a no brainer for me.

Filmmaker: There are some cinematographers like Roger Deakins who like to use the same gear over and over, but you’ve always been more agnostic. You’ve shot Red and Alexa, Arricam and Panavision, all sorts of different lenses. Why do you like to switch things up from show to show?

Libatique: I guess I’m a glutton for punishment. [laughs] I shot my previous four films anamorphic, which I absolutely love, but I hate to repeat myself over and over again. I start to feel like things are starting to look the same. I want every film to feel custom-made. So, I really wanted to switch it up and shoot spherically [on The Prom], mainly because I knew I had a large cast and didn’t want to impose this shallow focus vibe to a film that often had four people in a shot. I wanted to re-acquaint myself with the spherical lenses while having the added value of the larger sensor. So, I kind of wanted to see if I could basically have my cake and eat it too. I could accommodate the group shots, but I could also exploit the shallow focus [of the larger format] when concentrating on a single.

Filmmaker: For those spherical lenses, you used a combination of Leitz Primes and Camtec Falcons. How did you settle on those?

Libatique: I used the Leitz Full Frames for the first time on a short film with Olivia Wilde called Wake Up, experimenting with them on a Sony Venice. I just loved the fall off. I’ve always loved the soft fall off that their lenses have when something gets into the higher realm of the gray scale in the highlights. It has a quality to it: not too sharp, which I try to avoid, but sharp enough to have clarity and color rendition. So, from a technical standpoint I knew I was going to get performance out of those lenses. Going back to the notion that I wanted to shoot spherically and knowing that this film was going to be bathed in color, I thought these lenses would be perfect for it.

Filmmaker: And the Falcons is a set of 1960s rehoused full frame stills glass that Camtec put together?

Libatique: Yeah, they were developed by Camtec with Bradford Young for Solo. Brad has subsequently developed the Black Wings with the Tribe7 guys, specifically with Neil Fanthom. But for the Falcons they took an old set of Canon glass and started to play with the coatings and created what they called Falcons, appropriately named because they were made specifically for Solo. I wanted something that would cover the LF and that would, right off the bat, give me an optically different vibe from these Broadway characters to the characters from Indiana.

Filmmaker: So initially you’re using the Leitz glass for Broadway and the Falcons for Indiana. How did you blend the two sets once the Broadway characters invade Indiana?

Libatique: I do this timeline at the beginning of every show where I think about, “When would I switch technique?” For example, there’s a performance by Dee Dee Allen (Meryl Streep) called “It’s Not About Me” at a PTA meeting and we used Falcons for that. But it was also a moment where we brought our Broadway palette into this realistic world, while using the Falcons and some Black Wings I rented too just to get as many aberrations as possible. Then, slowly but surely as we get into the movie, I started to incorporate Leitz glass into the performance scenes in Indiana. The idea was this infiltration of this virus of Broadway [laughs] into this Indiana town with the Leitz glass, until finally most of the final performance is on that glass.

Filmmaker: How did you approach covering the big song and dance numbers? They play out in a lot of wider, moving shots where it seems it would be tough to incorporate multiple cameras at once. It’s not like an action scene where you can sit back with C and D cameras on long lenses and just pick off details.

Libatique: Absolutely. We would start with a moving master, then once we’d established what the main camera on the Steadicam was doing incorporate the jib arm, a Movi on a remote head or even a second Steadicam, which was a luxury I had. For every scene, whether it be narrative or musical, [director/producer] Ryan Murphy knew where he wanted special cuts to happen. He’s really well-versed editorially and knows what he wants. So, we would accommodate the master knowing that we’re going to cut to those special shots at certain moments. Ryan’s a man of bold choices. [laughs] He wanted the camera to move almost at all times.

Filmmaker: I read in an interview that you use an Excel spreadsheet to get organized, but I wanted more details about that. What are the headings in that spreadsheet?

Libatique: The spreadsheet helps me stay in tune with the arc of the narrative. I use it mainly so I can deconstruct every scene in parts. For example, Scene 31 might have four different parts to it where the tone changes or maybe a scene is handed off from one actor to another. Case in point is the final prom, where it starts off as a moment between two people finally getting together, then transitions to the resolution of each and every Broadway character. There’s a lot of parts to that scene, so I break it down for myself. That’s the only way I really know how to do it. I hate chaos and filmmaking is so chaotic. The more control you can place on what you’re after, the less chaotic it is.

But the chapter headings, I literally start off with scene number, description of the scene, then I have a heading that says, “Who’s the scene about?” Then I have columns for camera, lighting, grip, VFX, art department and write down notes for every scene about what I need from everybody.

Filmmaker: You had a great quote in another interview about how sometimes lighting needs to be the lead guitarist and sometimes it needs to be the drummer. In The Prom, you’re dealing with not only the subtle shifts in dynamics between characters that you just described, but also very showy shifts from reality into the realm of the theatrical, complete with stage-inspired lighting cues.

Libatique: It was fun, but you just have to ask yourself, “When is it too much?” Ryan is somebody who loves bold choices, but you know that at a certain point, there’s a limiter there. It’s like, “Okay, go, go, go, go. Whoa. That’s too much.” [laughs] That was the rhythm of our relationship and it’s an interesting way to work.

Filmmaker: I want to ask about how you approached lighting a few specific scenes. Let’s start with the party at Sardi’s, where Streep and Corden go to celebrate after the opening night of their Broadway musical about Eleanor Roosevelt. It’s a good example of how you incorporated lights into the production design.

Libatique: That was a classic collaboration between art department, production designer, cinematographer and lighting department. We had the ability to remove parts of the ceiling, but Ryan really wanted to see that ceiling, so we had to put units into the soffits that were able to both illuminate and change color. We live in a time when RGB LEDs give us so much flexibility. There were things that we were doing on this movie that we wouldn’t have been able to do five or six years ago.

Filmmaker: What units did you use up in the ceiling?

Libatique: We used a lot of LiteGear LED ribbon. The spaces were so thin that we weren’t able to put Asteras in those soffits. One layer of ribbon wasn’t enough, so we doubled them up just to get enough ambient value to bounce into the ceiling to accommodate the scene.

Filmmaker: Is the Eleanor marquee out that window a green screen replacement?

Libatique: No, they rebuilt that sign inside the stage. So we’re looking into the real thing there.

Filmmaker: Was it providing functional backlighting too on the characters close to the bar?

Libatique: I’m adverse to backlight as a general theme. [laughs] When I was in film school [Italian cinematographer Vittorio Storaro famously said “The world is backlit,” and he’s not wrong. But that backlight is not directed at a person, it’s the light from a background separating them. It took me years to understand that—I wasn’t looking for the light to hit somebody, I was looking for the separation that light created. So to answer your question, yes, it did hit them. There’s a shot that pushes into Meryl and James during the musical performance and you see these guys who basically have no light on them dancing around [the bar area], and the separation is coming from the light from that sign. The brightest light of a shot doesn’t always have to be on the actor’s face.

Filmmaker: I have to ask about the dinner scene between Streep and Keegan-Michael Key at Applebee’s, where you do a theatrical fade out that turns the place into a performance space. Is that a build or is that actually an Applebee’s?

Libatique: No, that was an actual Applebee’s. Again, this speaks to the current times. We had a camera with the sensitivity of the Mini LF and LED technology that allowed us to put battery-operated lights up without having to power them. We could rig them in places where they’re hidden and accurately have them all dim from 50 percent to zero to create that kind of effect.

Filmmaker: What would you like to finish up with: the monster truck rally, Meryl’s PTA meeting song, or the Bob Fosse-inspired number?

Libatique: Let’s talk about “Zazz,” the Fosse number. I would say I struggled with that one the most. That was the one where I really had to think about, “How far do I go here?” It was a build, but I’m still lighting a house to be a theatrical space.

Darren Aronofsky [Libatique’s frequent collaborator, including on Black Swan and Requiem for a Dream] and I sometimes will go to the theater in Broadway just to see lighting. I remember this off-Broadway play with Scott Glenn in it. He walked out naked and turned on one fluorescent light inside a kitchen set amidst this entire stage, and I thought that was so powerful. That was a case where they took a naturalistic lighting concept and put it in a theatrical space. I had to figure out how to do the opposite—to take a theatrical lighting concept and put it in a realistic space. For me, that was probably the hardest performance to pull off.

We used a combination of things: Arri L10s, which gave us that hot spotlight coming through the front window; Color Forces and Asteras creating this kind of marquee effect on the stairs; and SkyPanel S60s in the main windows of the foyer creating the color changes. Then I had this stupid idea of putting a 20K on a dolly track and moving it back and forth in front of the house because I just needed one more layer of absurdity. [laughs)]That’s where that hot highlight comes from—literally a 20K on a mini-crank with a guy making sure it wasn’t going to fall over, another guy on a dimmer and two grips pushing it back and forth the length of the house on a piece of track.

Filmmaker: You mentioned a few times how working with Ryan means pushing things right up to the edge. What’s the scene where you went the furthest past that line?

Libatique: There was a scene called “Dance with You” at the very beginning of the movie where Emma and Alyssa are walking through these magenta trees. It was such a big expanse, I had to do it old school. I had Bebee lights creating that color with gel. When you’re using LEDs you can change or desaturate the color. You can say, “That’s too much.” When you put gel on an HMI light, it’s like, “Well, that is what you’re getting.” That’s one example where Ryan was like, “I think it’s just too much.”

Filmmaker: Right. You can’t hop on the iPad and dial it back 10 percent in a couple seconds.

Libatique: No, not on the Bebee. There’s a limited number of things we could’ve done except maybe waste them into the neighborhood windows. (laughs)

Matt Mulcahey works as a DIT in the Midwest. He also writes about film on his blog Deep Fried Movies.