Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance 2021 Critic’s Notebook 2 (Abby Sun): I Was a Simple Man, Strawberry Mansion, Cryptozoo

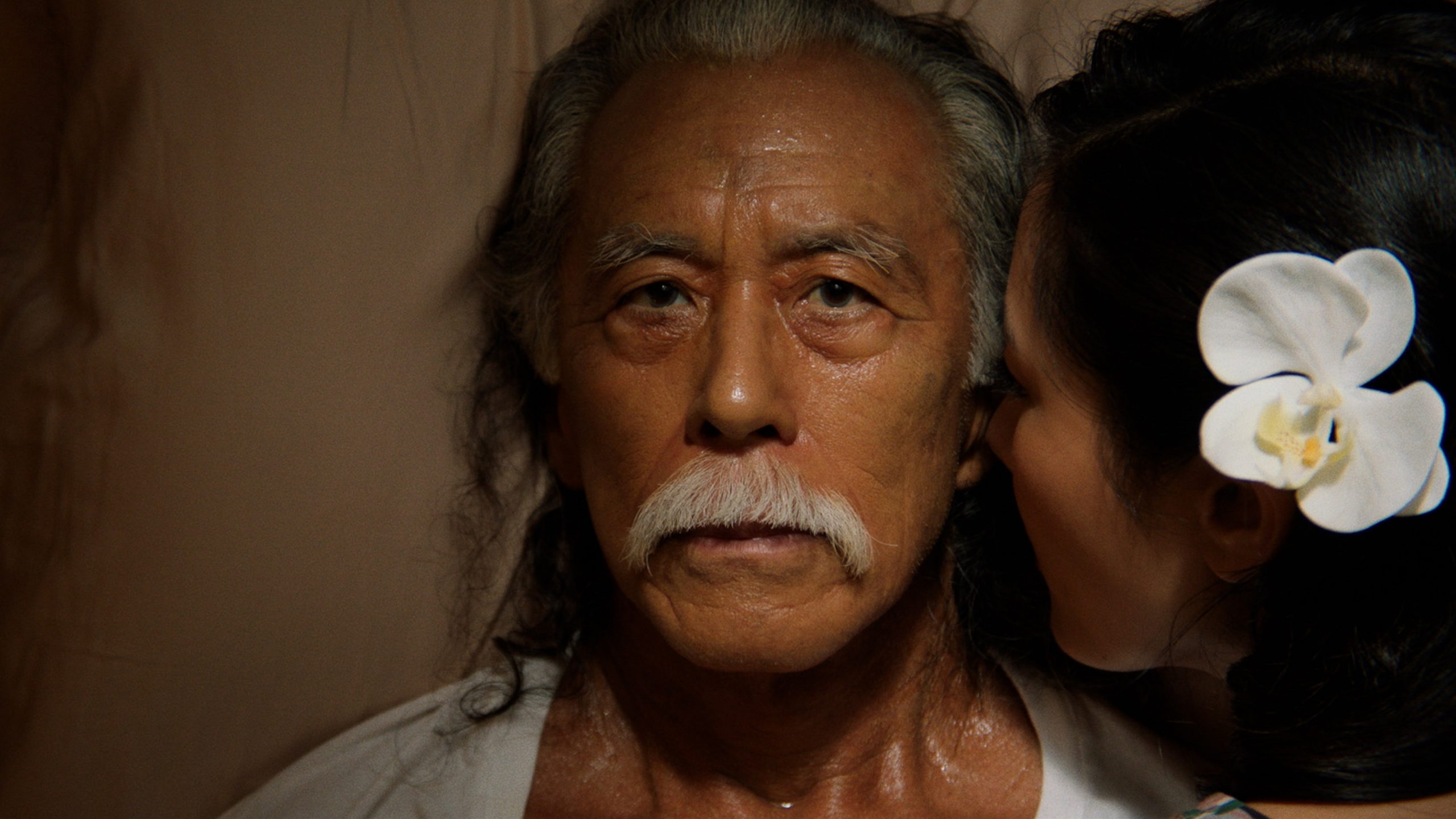

I Was a Simple Man

I Was a Simple Man The Sundance Institute has been running producer and director labs since 1981, even before taking over and renaming the former US/Utah Film Festival in 1985. In that sense, the projects coming out of the Feature Film Program (whose founding director, Michelle Satter, is still in charge), Indigenous Program and Documentary Film Program are just as important a marker of Sundance’s effect on the US film ecosystem as the platform provided by the festival. When I programmed film festivals, I tracked their press releases as closely as official lineup announcements. This year, 16 projects in the festival were officially supported by Sundance Institute programs—the one I’ve been anticipating the longest is Christopher Makoto Yogi’s I Was a Simple Man.

As with Yogi’s first feature, August at Akiko’s, the film’s languid pacing, use of non-professional actors and insights on Hawai’i time and history represent a continuation of Yogi’s interest in non-linear placemaking. While searching for funding for I Was a Simple Man—envisioned so long ago that Constance Wu was cast before Fresh Off the Boat became an Asian American pop culture touchstone—August at Akiko’s was developed second but finished first. In that film, Alex Zhang Hungtai (of Dirty Beaches) plays a musician named Alex looking for his ancestral home, only to stumble upon an agrarian retreat run by Akiko Masuda, who operates such a business in real life. Zhang, Masuda and other longtime key collaborators—like producer Sa Hwa Kim (previously credited as Sarah S. Kim), DP Eunsoo Cho and sound editor & mixer Sung Rok Choi—all reteam for I Was a Simple Man. I mention all of this because it illustrates how one person’s success within a system can uplift a whole group—and how exclusion can set subsequent generations adrift. That is precisely the locus of I Was a Simple Man’s straightforward plotting, which adds a couple standout set pieces and a talented, large ensemble cast to a basic premise following main character Masao’s terminal diagnosis.

As Masao, played by three performers at different ages, grows frailer, the ghosts of his present, past, childhood and ancestral forces merge by his bedside in physical and temporal forms. Starting in the present: his three children are alternately begrudgingly dutiful—too stoned to take care of themselves, let alone their father, resentful and absentee after extracting themselves to the mainland. The highlight of this opening act is a meeting older Masao (played by local resident Steve Iwamoto in his film debut) has with his neighbor, Akiko (Masuda’s vivacious return in a scene-stealing cameo), who tells him to stop fighting his illness. One night, Masao finds the ghost of his dead wife, Grace (Constance Wu), has come to keep him company in corporeal form. She’s not a vengeful spirit, nor prone to speaking or offering direct comfort. But her presence catalyzes a series of flashbacks—or meanderings—that reveal Grace died on the day of Hawai’i’s statehood on August 21, 1959, forever tying together colonized self-actualization with tragedy for adult Masao (Tim Chiou), who sent his three young children to live with extended family and prepared himself to, as he says to a friend, “drink until I die.” Since the opening scenes shows older Masao refusing to take his doctor’s advice to stop drinking and smoking, this is on-the-nose (as is dialogue like the repetition of “Dying is simple, isn’t it?”), but because of the film’s cyclical structure I presume Masao has done precisely that.

The hollowness of Masao’s life, and manifestations of his regrets and choices, are supplemented by a lush sound mix; his bungalow’s creaking breathes like a sentient character (place-making, indeed) when Masao himself doesn’t speak, as in much of the latter half of the film. This portrayal is contrasted with the perceptive acceptance of his grandson Gavin (Kanoa Goo), whose interactions with Masao result in one of the most affecting scenes in the film, and whose actions are shown as a sort of an alternative life to his grandfather’s. Though young Masao (Kyle Kosaki) was warned by his parents to avoid even associating with a teenaged Grace (Boonyanudh Jiyarom) because they didn’t approve of her Chinese ethnicity, Gavin is allowed to roam the Oahu countryside freely. A punk skateboarder, he’s heckled walking down the road, but exudes cool when hanging out with a female skater one evening. Unlike the fraught and clumsy interactions Masao has at three different ages with friends and family, Gavin’s way of inhabiting the world doesn’t reject the past, his identity or the pains of belonging. If Gavin and If I Were a Simple Man are, respectively, the future of this country and its independent filmmaking, we’re in good hands.

Two other films about dreams, ghosts, manifestations and their commodification are premiering at this year’s Sundance. I quite enjoyed Albert Birney and Kentucker Audley’s first feature collaboration, Sylvio, a tongue-in-cheek parable about a gorilla that becomes local-famous for his authentic self, then is eaten up by the media apparatus and pressured to conform to expectations as a result. Their follow-up Strawberry Mansion attempts the same wry, hipster-ironic tone in more fantastical settings. Drawing upon VHS nolstagia, everything in this film looks like it’s in the ’80s, but infused by a futuristic technology in which the state taxes objects that appear in dreams. Audley (who has appeared in many a Sundance film over the past decade and also runs the fervently-low-budget streaming showcase NoBudge), stars as James Preble, a dream auditor whose current job is to collect the back taxes, dream-edition, of an old woman named Bella (Penny Fuller). Preble’s peeks at Bella’s dreams reveal a younger version (Grace Glowicki, herself an actor-director whose Tito was a 2019 indie standout) he becomes awkwardly enamored with. Birney’s uncle, veteran stage actor Reed Birney (who also stars in another Sundance film, Fran Kranz’s chamber piece Mass), is suitably sleazy as Bella’s adult son, who turns out to have a huge financial stake in discrediting his mother and keeping Preble placated.

Halfway through the film, Bella reveals corporations clandestinely beam advertisements into everyone’s dreams; hers are so compelling because they’re free of unwanted product placement. Stuck in a dream, Preble is jerked to and fro; while he searches for the younger dream-Bella to rescue her, she’s trying to convince him to escape the shackles of dream-dependence. This literal manifestation of a manic pixie dream girl, whose sole narrative purpose is to help Preble reach his self-actualization (and save himself from a house fire in the real world), reduces the playful, sly character of the older real-world Bella into someone disappointingly flat. It’s a shame, because the set and production design are often creatively, bombastically out-there, cheekily drawing on references from Méliès’s hand-coloring and animation to glitches rising from its digital-to-film process. Strawberry Mansion’s trick, in the end, is not that commercial-free, pastoral dreams of the past are a more liberatory place. Instead, in this world, the ad-free experience is merely a less mediated way to immerse ourselves in retrograde nostalgia; Preble frees himself to escape back to his pristine, cookie-cutter modern apartment, boot up his dream-viewing-machine and plug back into dream-reality, where he can immerse himself in a chaste, cottagecore dream-life with young Bella (who, at this point, only lives on in dreams). In actuality, we’re not limited to premium ad-free streaming services or stopping every 10 minutes to watch with or interact with ads on a cheaper or free version—we can choose to, you know, opt out of participating altogether.

With a completely different aesthetic but still DIY-feeling approach, Dash Shaw’s Cryptozoo starts in a kind of Edenic but decidedly unchaste counterculture 2D animation world of 1960s-ish America, where “cryptids”—mythological creatures from all stripes and cultures—exist alongside humans. Taking a similar allegorical approach to discrimination and persecution as X-Men, the plot of this film centers around a “cryptozoo” founded by a philanthropist (voiced by Grace Zabriskie), aimed at providing a sanctuary and livelihood for the cryptids on display in its theme-park-esque exhibits, and populated by the recruitment activities of human cryptid-advocate Lauren Gray (Lake Bell). Gray has been obsessed since childhood with a baku, a Japanese, pig-like devourer of dreams who graciously consumed Gray’s nightmares as a child on the US postwar military base at Okinawa (itself a contested site of Japanese imperialism in the Pacific theater). Now, the US military is after the baku for its potential to destroy the dangerous counterculture dreams of 60s activists seeking to decolonize the world (and the US military-industrial complex).

Cryptozoo’s moral concerns are mostly enacted in conversations between Gray and Phoebe (Angeliki Papoulia), a gorgon, who argue about the patronizing and spectacularized exhibits of the Cryptozoo vs. Phoebe’s assimilationist approach of tranquilizing her snakes in order to live life passing alongside her human husband. Other reviews draw parallels between this film and the dangers of humans believing they can control monsters for entertainment, most notably in the Jurassic Park films. But, to me, more scathing and apt comparisons can be found with with the very real, very present theme parks for little people; the “living exhibits” of “savages” at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair that included over a thousand resident Filipinos; recent controversy over Berkeley anthropologist Alfred Louis Kroeber (father to feminist scifi author Ursula K. Le Guin, whose later works grappled with the colonial legacy of anthropology); and recent revelations that Harvard museums have the human remains of over 22,000 Indigenous and enslaved Black peoples. This is not the stuff of the purely fantastic, the future or even purely of the Anthropocene—like this film’s time period of half a century ago, it’s a colonial legacy we must grapple with now. The sentience of all the cryptids, including the non-humanoid ones, drive the violent last third of this film. Though the entertaining abduction-and-rescue nature of the plot becomes rather convoluted at times, Cryptozoo keeps a bull’s-eye-view target on the nature of gratitude, solidarity and political liberation.