Back to selection

Back to selection

Sundance 2021 Critic’s Notebook 4 (Abby Sun): R#J, We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, Rich Kids: A History of Shopping Malls in Tehran

R#J

R#J As I hinted in my first entry on Sundance 2021, I’ve spent a couple hours a day on the festival’s browser-based New Frontier space, which houses all 14 projects in the New Frontier selection, a space for watching select films in VR and Film Party, an online proximity-based video and audio chat space. There’s also a digital ferry from the Gallery to IDFA DocLab’s do {not} play platform, which was for IDFA (the world’s largest documentary festival and marketplace, held in Amsterdam in November of every year) what Film Party is to Sundance. Navigating the Sundance digital platform through my browser window, I can move my avatar via arrow keys towards other people, identified with floating text above their heads (or I can search through a sidebar listing the names of everyone in the space and head directly to someone for networking). Once I get within a certain distance, a prompt appears for me to enter a chat space, which unlocks the chatting function. In VR, however, movement is through a teleportation function, and there isn’t a video chat function, only audio. I can, however, move my avatar’s arms while holding the controls. The difference between facial and body movement-based communication is clearly demarcated by these experiences, but both proved personable.

In Film Party, I’ve encountered industry acquaintances of the sort I wouldn’t typically text or email casually. In this way, Film Party serves as the communal watering hole that would have otherwise been the lobby of the Park City Doubletree Hotel, or the line at its Starbucks or to get into a film. And, just like at a real party, others can join in, eavesdrop or insert themselves into the mix. I experienced strange moments when a few fellow conversationalists and I discovered a digital wormhole from Film Party to do {not} touch—our avatars were standing in the main Film Party room, but we started hearing snippets of conversations from people not in our proximity-enabled, viewable chat circle. One such digital ghost recognized the voice of someone in my group, and after chatting, we all worked out that the “Want to meet up in the restaurant?” floating voices we’d been hearing were not referring to breaking lockdown restrictions but to do {not} touch’s distinctive bar-themed rooms. In addition to folks I already knew, I’ve also met some interesting people who don’t have projects at Sundance this year, who are looking to get a lay of the industry and the burgeoning VR space. The best conversations happen when we have something in common to discuss. Without walking out from a film premiere together, I found that most of my conversations started with everyone exclaiming over the platform of Film Party itself. Film Party attempts to encourage such gatherings by rotating out recently premiered films and New Frontier projects on giant screens within the space, which are suspended above portals to other, smaller rooms themed around the films. Mostly, I’ve found that these rooms stay pretty empty, but if a certain amount of folks enter, it can create its own threshold effect and the feeling of a party-within-a-party.

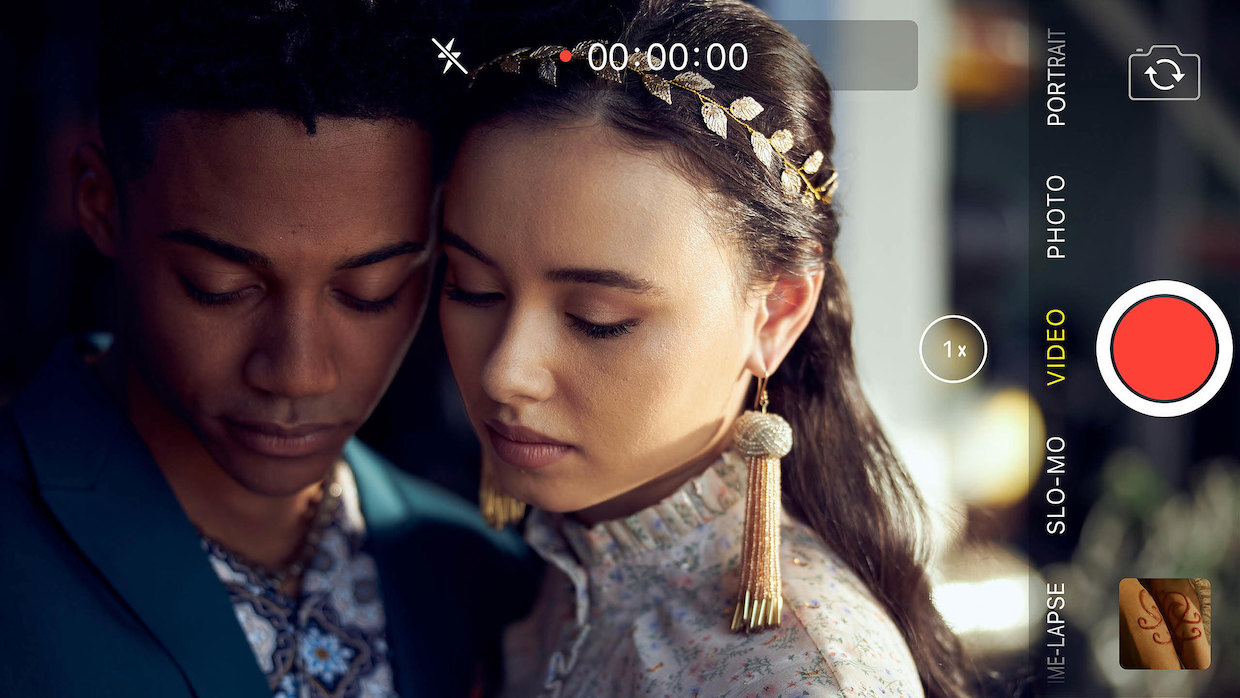

Moving on to films, one of the highlights of the NEXT section is Carey Williams’ R#J, produced by desktop cinema maven Timur Bekmambetov (who also shepherded Unfriended, Searching and so forth). Given the new interest in screen life, and my own immersion within Film Party, it’s easy to dismiss the Screenlife-formatted R#J (the curious use of the hashtag in the title is explained in the film as the tag Juliet signs her artwork with) as a simplistic attempt to make the doomed Shakespearean couple relevant to Zoomers. I don’t think, however, that even the youth need any introduction to Romeo and Juliet, though perhaps middle school English teachers would welcome an updated version to show their students at the end of a unit on the play. First, R#J is well acted. Juliet is played by an appropriately ethereal Francesca Noel (last seen in Selah and the Spades) as an earnest influencer- and artist-type unaware of the political machinations between her family and the Montagues. Camaron Engels is knockout as the yearning Romeo, and Siddiq Saunderson gets the star turn of Mercutio. Every character gets their due, not just Romeo and Juliet. In that way, R#J is a satisfying, polyphonically grand tale of intergenerational conflict. The actors infuse an immediacy to the Shakespeare dialogue that drives all the scenes filmed, and presented to us as, Instagram Lives or Facetimes, often in split screen.

The film is hip and cool, overwhelmingly so. (Romeo has the Criterion Channel app on his phone and even Letterboxd makes an appearance, but for some inexplicable reason, the characters all leave the typing sound on their phones—can we get rid of this on-screen artifice once and for all?) Where previous Screenlife films took pains to confine the action to a singular desktop, R#J jumps between phone screens, including before and after live broadcasts. Large portions of the film take the form of sequences where we see what characters are typing in response to long text threads, viral videos, slut-shaming comments and other internet pile-ons, while hearing their diegetic vocal reactions (gasps, mutterings). The transitions are as slick as the IG grids on the subject’s phones—this is very commercialized phonetop cinema. Most interestingly, this film takes ample advantage of these technological artifacts—the video preview in Facetime, read receipts, the “…” that signals so much anticipation and anguish—to dramatic effect.

There have been other modernized versions (a pirated version of Romeo + Juliet was one of my well-loved DVDs), films focusing on side characters like Mercutio and other versions with color-blind casts. To be clear, this film pushes some boundaries and lets others go too easily. Romeo and Juliet’s shotgun wedding is marked by a literal branding sequence (personal brands to the max), and it repeats some easy conclusions about the dissemination of “fake news.” At that level, the film is a good enough record of current social media and doesn’t really aspire to much more. But R#J is unique for attempting a new ending that complicates the previously indiscriminate trip through the private- and public-facing social media presences of the Montagues and the Capulets. At first, I felt confused (caution, what follows will reveal the ending): Why didn’t I know about this Finsta beforehand? But then it struck me that the film’s new ending does something quite clever, if infuriating to purists. The problem with typical approaches to color-blind casting is that the specificities of experience don’t really fit. R#J casts that aside by embroiling the Capulets and Montagues in a feud marked by the police brutality facing Black people in this country. To keep an ending that glorifies the deaths of Romeo and Juliet, then, merely re-enacts the spectacularizing of Black death. Why shouldn’t our modern star-crossed lovers find their happiness?

Bekmambetov’s Screenlife format takes advantage of the pandemic ways of living on screens and is supported by a deal with Universal, but the NEXT section also offered less standardized ways of presenting internet culture. In contrast to the relentless connectivity of R#J, Jane Schoenbrun’s We’re All Going to the World’s Fair never shows two characters onscreen at the same time, taking place primarily in private bedrooms where we gaze not at the character’s screens but at their faces as they post and livestream videos into the void. Like Nerve, World’s Fair centers around a massive multi-player online “game” that challenges participants to a series of dares; like the daredevil stunts of that film, the prompts of this game require its players to inflect harm on their bodies, but in much more intimate, private ways. The form of World’s Fair is an uncompromising affair, opening with a long shot of teenaged Casey (newcomer Anna Cobb, in a supremely affecting turn) rehearsing, then recording, her first video to accept the World’s Fair challenge. She repeats the open sesame phrase three times before repeatedly stabbing her finger with a pin, then smears her computer screen with her blood (but off screen). These one-shot scenes appear several times, representing a sort of durational immediacy as Casey becomes embroiled with the World’s Fair challenge. Sometimes, like the opening shot, the webcam is the camera’s point of view; other times, we’re off to the side. Questions of loneliness aside, World’s Fair sensitively captures the sense of discovery and isolation online anonymity provides, and the long shots go a long way towards establishing that atmosphere. The film comments upon creepypastas and, crucially, itself fits the genre.

Midway through the film, the perspective shifts from Casey’s to JLB (Michael J. Rogers), a stranger who becomes obsessed with her videos and wellbeing. He’s introduced via a message Casey receives, then World’s Fair cuts to middle-aged JLB’s dowdily furnished house, where he lives alone and watches Casey’s videos avidly—in World’s Fair, it is the anxious single man who insists on the truthiness of Casey’s videos, not the naïve teenager herself. But World’s Fair’s operational images aren’t quite our own. There is a sequence of YouTube-style videos of other World’s Fair challenge participants, which shows the horror-inflected ways they have been affected by the challenge (one man gets pulled into a laptop screen). Though these aren’t direct YouTube screen captures seeking to replicate the platform’s distinctive look, they bear some of the artifacts of YouTube’s “recommended videos” function. There are bits and pieces that borrow from other creepypastas (Schoenbrun wrote a long piece about Youtube fan mutations and creepypastas, if one is curious about how this filmmaker’s interest in how content gets spread online goes beyond the surface-level polish of R#J.). The found footage aesthetic seems to establish the veracity of the body horror Casey is anticipating, but there is an alternative reading in which World’s Fair is actually a distribution platform for its own form of narrative psychological horror.

The last act of the film shifts completely from Casey to JLB (and it’s crucial context for considering the film’s conceptual momentum, so consider yourself warned about spoilers for the rest of the paragraph). After a fraught video call in which Casey yells that isn’t even her real name, she refuses to talk to JLB more after accusing him of pedophilia. JLB is visibly shaken and the film ends with JLB narrating a bit of epilogue text while still staring into his computer screen—it’s ambiguous whether what he’s saying is what happened or whether he’s crafting a semi-happy ending for Casey after months of no contact. At this point, it’s deliberately unclear who is the creator and who the consumer of World’s Fair creepypasta. Herein lies World’s Fair own strangeness: for all its present-tense durational qualities, it best encapsulates an unspoiled vision of the internet as a place for one-on-one interactions and solitary discovery. I’m still puzzling through whether the film yearns for these supposed golden-days of internet-based self-actualization, and whether it’s positing their continued existence today.

Outside of filmmaking, Schoenbrun toured the well-curated, weird-inflected shorts series The Eyeslicer across the US, and also co-hosted the wildly successful Radical Film Fair with Kickstarter, which provided space for independent distributors, magazines, zines and screening series to peddle their wares to a packed audience in September 2019. Knowing this, I laughed at the cameos by filmmakers in World’s Fair and its record as an expression of the relational nature of independent filmmaking. Albert Birney (whose co-directed Strawberry Mansion I wrote about a couple of days ago) is named as the animator. The dream-viewing-machines of Strawberry Mansion look like tethered VR headsets, in a retro-steampunk kind of way, so seeing Birney’s name in the credits refigured Strawberry Mansion for me as a defense of the palliative effects of VR, casting an even darker tone over that film’s pastel aesthetics.

At Sundance, there were alternative visions more critical of the flattening effects of livestreams, which fully understood the ephemeral nature of such interactions and didn’t seek to memorialize their surface-level aesthetics. The most thought-provoking of these wasn’t a film, but a simultaneous YouTube live and Instagram live performance, Rich Kids: A History of Shopping Malls in Tehran, produced by the Javaad Alipoor Company and starring co-lead artist Alipoor and actress Peyvand Sadeghian. The two share a split screen on YouTube Live and Instagram as they live-narrate a speculative fiction about the lives of Mohammad Hossein Rabbani-Shirazi and Instagram influencer Parivash Akbarzadeh in the final days leading up to their deaths in a car crash that went viral online.

Rich Kids lays out the facts of their Instagram popularity and the media effects of their deaths pretty quickly. The two frequently posted online photos that displayed Rabbani-Shirazi’s wealth and Akbarzadeh’s status as his girlfriend (while he was engaged to another fiancée); their deaths, and the image of the mangled Porsche they were driving after attending a champagne (Bollinger) and cocaine-laden party, inspired massive anger from the Iranian middle-class, who have had to live with worsening political and economic austerity as the country’s elite take advantage of political power to enjoy the luxury comforts of the West. Along with this movingly and imaginatively performed thread, Alipoor and Sadeghian also enfold a performance lecture covering the iconography of wealth from centuries ago through the present, human conceptions of time and theorizations of the Anthropocene and, naturally, a topographic and cultural history of shopping malls in Tehran and their meaning as public gathering places to see and be seen. Their demeanor is welcoming and generous, walking audiences through when to participate by interacting with phones and when to watch the screen. The images on the screen(s) veer between their talking heads, digital schematics, depictions of the speculative history they create and computer-generated abstractions. The pacing is just right and the connections complex.

Rich Kids uses the specificity of the car crash to imagine rich inner lives and conflicts for its victims, calling on but hurtling past the narrow conversations in media about how images are disseminated to create linkages with much longer, non-human time that we must understand in order to confront the global problems plaguing us: nuclear waste, climate change, imperial inequality. The thread that stuck with me most is Rich Kids’ understanding of media effects, and how individual practitioners—whether artists, plebians or rich kids—both contort ourselves to fit within the restrictions, and can also détourne within these same platforms in resistance and deliverance. Rich Kids was first produced to great acclaim (including an award at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe) as an IRL live performance, with Alipoor and Sadeghian sharing a stage but still incorporating the IG Live portion of the show. Their performances in purely digital form at Sundance, repeated in several time slots, were first developed over the summer. The live element is crucial, with the final act hinging on a notion of ephemerality. As Sadeghian concludes: “Some things we dig up. And some things we bury.”