Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“Am I Going to Have to Reshoot Half of This Movie?” Howard Deutch on Some Kind of Wonderful

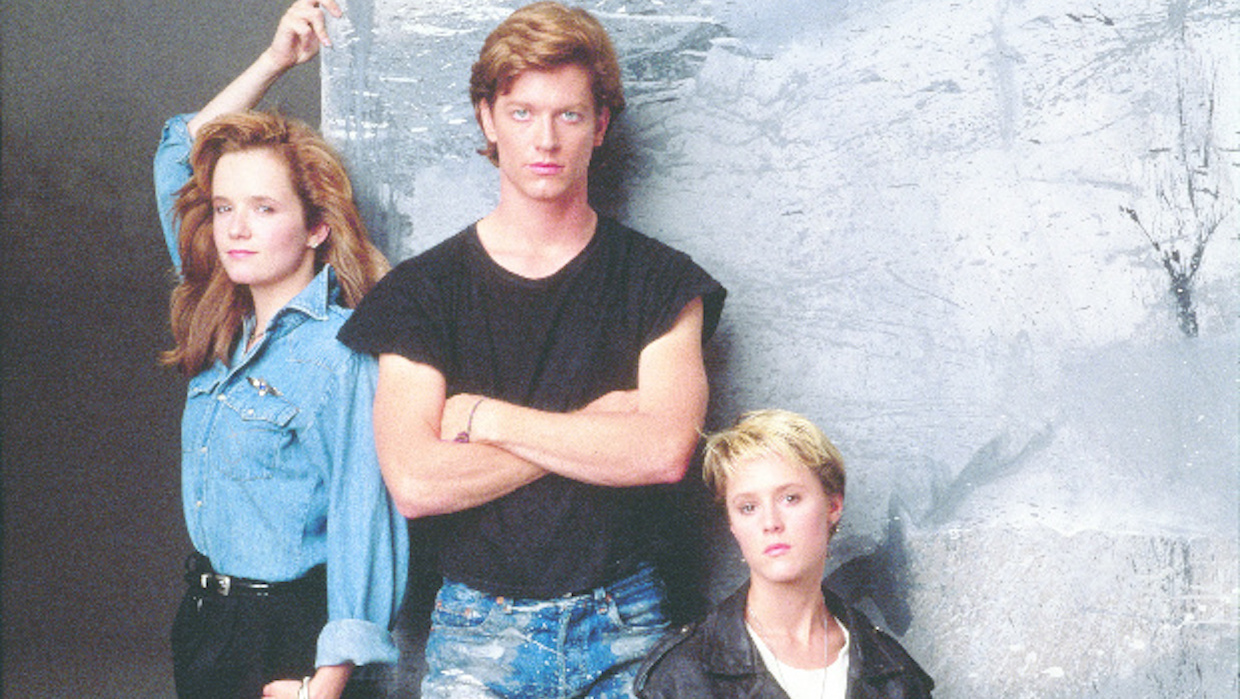

Mary Stuart Masterson, Eric Stoltz and Lea Thompson in a publicity image for Some Kind of Wonderful

Mary Stuart Masterson, Eric Stoltz and Lea Thompson in a publicity image for Some Kind of Wonderful Writer-director John Hughes had just begun to make a name for himself with three films he made for Universal (Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club and Weird Science) when Ned Tanen lured him over to Paramount with an overall deal designed to turn the filmmaker into a mogul. In less than three years, Hughes wrote, produced, and/or directed five movies for the studio (Pretty in Pink, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, Some Kind of Wonderful, Planes Trains and Automobiles and She’s Having a Baby), all of which have now been reissued on Paramount’s “John Hughes 5-Movie Collection” Blu-ray with a generous supply of extra features, including a terrific piece in which Kevin Bacon interviews Hughes about Some Kind of Wonderful and She’s Having a Baby. Those two films make their Blu-ray debut in the package, and it’s great to rediscover them alongside the other three more widely celebrated movies; for me, She’s Having a Baby remains Hughes’ finest film as a director, witty and wise and self-deprecating, with an impeccably calibrated comedic performance by Kevin Bacon that shifts into a higher emotional gear in the picture’s deeply moving climax. It was not only Hughes’ best film but his most autobiographical and self-critical—and unfortunately, his least commercially successful. Its failure led Hughes to focus on broader, less personal comedies like the Home Alone series and a series of anonymous remakes and reboots (Miracle on 34th Street, 101 Dalmatians, Flubber) for the rest of his career; his best work was thus concentrated in a period of only around four years (from Sixteen Candles in 1984 to She’s Having a Baby in 1988), but in that four years he had the best run of any American writer-producer-director since Preston Sturges in the 1940s.

For his first production under the Paramount deal, Hughes chose to hand the directing reins over to Howard Deutch, a first-time feature filmmaker who had cut trailers for earlier Hughes movies like Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club. The result, Pretty in Pink, would become a high point in both men’s filmographies thanks to Deutch’s careful attention to both visual detail and performance; it’s one of those debut films where a director with a lot to prove does so by infusing every frame with passion and artistry, resulting in a movie that’s got all of Hughes’s strengths in terms of observational humor and empathy but also feels more lived-in and authentic thanks to Deutch’s naturalistic and spontaneous approach. Deutch and Hughes’s follow-up collaboration, Some Kind of Wonderful, is equally strong, thanks in part to a working-class San Pedro setting that separates it from the suburban Chicago environments of Hughes’s other 1980s productions. Some Kind of Wonderful is funny, touching and another example of Deutch’s immense sensitivity when it comes to young performers; as the three members of the love triangle at the film’s center, Eric Stoltz, Mary Stuart Masterson, and Lea Thompson (who Deutch would later marry) perfectly capture what it’s like to be teenagers who feel uncomfortable in their own skins, and Deutch perfectly captures those performances with lens choices and framing that emphasize the characters’ loneliness, vulnerability, and giddy excitement. The movie’s effectiveness is all the more remarkable given the chaotic nature of its production, which Deutch joined late in the game; on the eve of the new Blu-ray release, I spoke to him by phone to get the story on how he pulled the film together.

Filmmaker: Let’s start with the origins of Some Kind of Wonderful. How different was the initial script from the movie you ended up making?

Howard Deutch: Totally different movie. It was a really hilarious comedy about this guy whose dream is to go on the greatest date of all time. He orchestrates a date that includes the Blue Angels flying overhead at the restaurant they’re in and stuff like that, and it was really an outrageous comedy, nothing like what we ended up making. And I didn’t know how to cast it, except for Michael Fox. I thought, “Michael Fox can do this,” and called him myself—I was so naïve I didn’t know that wasn’t how you did things. The next thing I knew, his lawyer and agents were calling me, screaming, “Who do you think you are, calling him directly?” But he passed, and then I didn’t know what to do.

I’d directed Pretty in Pink, but I was still a beginner. I was on a plane where I ended up sitting next to Brian De Palma, who I’d met once but didn’t really know very well. I told him about this thing that I was doing and that I didn’t know how to cast it. He just said, “Well, if you can’t cast it, you shouldn’t do it.” I thought, “Well, if Brian De Palma thinks I shouldn’t do it, I probably shouldn’t do it.” So I told Ned Tanen, the head of Paramount, “I don’t think I can cast it.” And the next morning, there was a padlock on my office. I was persona non grata. I was thrown off the studio lot. John wouldn’t talk to me. Everybody was mad at me. And I was like, “What?” I had no idea how much trouble I was in. There was another movie John had written called Oil and Vinegar that I wanted to do, and I thought I could just switch to that. But he was really upset with me.

Filmmaker: And Hughes was a notorious grudge holder. How did you get back in his good graces?

Deutch: Not easily, that’s for sure. They had hired another director for Some Kind of Wonderful and John had tailored the script to this director, making it more dramatic. I got a call from Ned Tanen one night and he asked me, “Did you ever see Day for Night, the Truffaut movie?” And I hadn’t. He said, “Go to the video store right now and rent it, because it’s the story of your life.” So I watch Day for Night, and I go, “Yep. That’s the story of my life.” And Tanen said, “Look, John is not having a great time with this other director. If you want to get back in, here’s your chance.” I met with John and he let me back in, and we were fine again. But the train had left the station. They already had locations, they hired a crew, they hired a cast.

John asked me what I wanted to do, and I said the main thing I needed to do was recast it. So I hired Lea, recast every other part except for Eric and jumped in. I was playing catch-up from the get-go, but that’s how it all went down. The most important thing is, once I started, John went back and made the script a little bit more comedic again, though not to the extent that it was originally.

Filmmaker: How did you deal with the challenge of so little prep time?

Deutch: Well, the key was the trust I had in the cast I had chosen, and in Jan Kiesser, who was a terrific DP. He did beautiful work, and he and I got along great. Everybody else, if I didn’t fall in love with them I just made the best of it, though I was lucky—most of them were terrific.

Filmmaker: You had a great director of photography on Pretty in Pink too, Tak Fujimoto.

Deutch: I can’t possibly give enough praise and thanks and gratitude to Tak, because he was my teacher. I almost didn’t hire him…I was meeting every cameraman in LA, and he came in and didn’t say a lot, because he’s not that vocal. But I kept thinking about him and I asked him to come back, and I said, “Look, you have to talk. If you don’t talk, I can’t hire you, because I need to talk. I’m nervous. This is my first movie.” And he said, “Well, I don’t talk a lot, but I’ll do a great job for you.” I was like, “Okay, thanks. This isn’t going to work.” He started to leave, then as he gets to the door to leave, he turns around and says, “I really need this job.” There was something about that moment and I just fucking did it, I hired him. And it was like the movie gods were looking out for me, because he not only saved my life creatively but politically. He did it in every possible way a friend can do it and a teacher can do it, and he’s more responsible than any other person for Pretty in Pink. There’s so much of him in that movie, from the economy of the visual style to the locations to the humor…having a kind of grace and belief in letting character drive the comedy, that’s Tak.

I remember going to my first location with him and he said, “What do you think? How do you like this for the record store?” I said, “I don’t know.” He said, “Well, that’s okay. Think about it like this. How does it make you feel to stand in this space? Emotionally, not technically.” Then I started to understand how to make those decisions. I can’t articulate how important he’s been to me. I ended up doing three movies with him.

Filmmaker: And he shot Ferris Bueller for Hughes, which is one of Hughes’ most visually elegant movies.

Deutch: Yeah, as soon as John saw Pretty in Pink, he was like, “I want that guy.”

Filmmaker: Back to Some Kind of Wonderful. You were talking about playing catch-up the whole time…

Deutch: I was, to the point that by the middle of the shoot I had lost faith in the movie. I was so exhausted, just trying to get my arms around it. I thought, “This girl chauffeuring around these two on a date, is anybody going to believe this?” I had a feeling no one would. I started to lose faith in it and in myself, so it was an uphill fight the whole time. I just didn’t know that it would work, and you can’t show that to the cast and crew—they would smell the blood. So I was performing; I’m the director, so I have to act like a director. But then whenever I had some private time I would just collapse. I don’t want to exaggerate, but I really did feel that movie was a trial by fire. Can I get through this and make it as good as it possibly can be? Remember, I had just come through a situation on Pretty in Pink where we had to reshoot the whole ending. So I was thinking, “Am I going to have to reshoot half of this movie, and is it going to work?” I didn’t know if I could live through that again.

Filmmaker: How quickly did you realize you were in that kind of trouble?

Deutch: It started with Eric on the very first day of shooting. He had long, long hair and you could hardly see his face. I got a call from my agent, Jack Rapke, saying, “Ned Tanen is calling me saying you’re punishing him. You can’t even see the actor’s face.” I said, “Why would I punish Ned Tanen? I love Ned Tanen.” He said, “Because he didn’t give you enough time or money or whatever.” I said, “I’m not punishing him, I’ll have Eric cut his hair.” So I cut his hair. And then they called again and said, “Why are you punishing him again? You cut Eric’s hair. Now they’ve got to reshoot the whole first day.”

It started off like that. And Eric was much better and more confident, and more secure as an actor, when he had the long hair. Once we cut his hair off, I felt like he didn’t have a character. I realized, this is the guy who played Rocky Dennis in Mask, so he’s comfortable hiding—now I’ve cut all his hair off and he’s exposed. So I’m fucked. And I thought, “Well, I’ve got to find a way to use that. Maybe this is a good thing for the character to feel exposed and vulnerable and like his skin’s on fire the whole time.” We did it that way, and it worked. I did many, many takes on that movie, probably more than I’ve ever done on anything else—I never gave up until I got what I thought I needed emotionally. Many times, Eric’s choice was to play it contained, and I wanted it to feel like there were higher stakes, or to seize the moment or whatever it was. It was worth it, because in the end, people love that performance. And he was terrific, but it was not like, “Okay, let me see what you feel good about doing, then we’ll move on.” It was never like that.

Filmmaker: One of the things I like about the movie is that the love triangle is genuinely suspenseful—you really don’t know who Stoltz will end up with, because Lea plays what could have been a one-dimensional object of desire with a lot more complexity and honesty than you might have found in a more conventional teen movie of the era.

Deutch: Well, I’ll take credit for the triangle, because that was my big concern. I knew that for the movie to work no one could know who was going to wind up with who. But I can’t take credit for Lea’s character. That’s all Lea. She honestly brought all the dimension to that, and elevated it, and made the character everything that you see. All the behavior, she brought to that.

Filmmaker: Something else that makes the movie stand apart is the San Pedro setting, which is very unusual for a John Hughes movie—it’s one of his only scripts from that era not set in the Chicago suburbs.

Deutch: He wanted a more industrial feel, to have Eric’s character come from someplace a little harder than suburban Lake Forest. He and the other director chose San Pedro, and when I hopped on the train I said, “Okay, it’s San Pedro.” Not, “Oh, let’s change that.”

Filmmaker: I love the opening credit sequence where you introduce all the characters in a montage set to Mary Stuart Masterson’s drumming and see Eric playing chicken with the train…

Deutch: We’d never be able to do that today. Without telling me he was going to do it, after the first or second take, he walked right in front of that train, like inches away. It’s not just a long lens. That could have been the end of it right there. That’s the kind of guy he is. He said, “Watch this,” and I almost had a heart attack.

Filmmaker: Part of the John Hughes mythology is how fast he wrote his scripts. But I think it’s a little bit deceptive, because he also rewrote them constantly while shooting. What kinds of new things did he add to Some Kind of Wonderful once you were in production?

Deutch: It was amazing. First of all, what John called the “kiss that kills” scene wasn’t in the script.

Filmmaker: The scene where Eric Stoltz practices kissing with Mary Stuart Masterson, who’s secretly in love with him? That’s the best scene in the movie!

Deutch: I know. It didn’t exist. John came up to me and said, “I think we need a ‘kiss that kills’ scene,” and he wrote it right there, in an hour. He would do that all the time. I was shooting a scene at breakfast with the whole family. Eric comes down after his first date and everybody is looking at him. I’m shooting, and the AD comes up to me and says, “I think we better take five. Something just came in for you.” I said, “Okay, cut.” I go in, and there’s a whole new scene John sent in. I took an hour to look at it and figure it out, then went back and shot it the rest of the day. And it was a better scene than what was there.

That happened all the time. And he was fast. I remember one time I was sleeping in his office—we would have dinner, then I would fall asleep in his office around ten while he was out back writing all night and chain-smoking. One time I woke up at around six in the morning and he handed me 50 pages. I thought he was doing a small rewrite on Some Kind of Wonderful, but he handed me these 50 pages and I looked at the title page and it said Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. I said, “What is this?” And he goes, “I don’t know. I don’t know what it’s about. But do me a favor, read it. Tell me what you think.” He had written the first half of that script in seven or eight hours. Then he finished it a couple of days later.

Filmmaker: Wow. All three of the movies you directed for Hughes—Pretty in Pink, Some Kind of Wonderful, and The Great Outdoors—have endured and gone on to have followings decades later. How were they received at the time?

Deutch: The critical response was just about what it was for his other movies. I mean, Sixteen Candles never got the greatest reviews, and The Breakfast Club was not adored and admired like it is now. Pretty in Pink did okay. Some Kind of Wonderful was slammed as being “Pretty in Blue.” I remember walking through the airport with John when we were on a press tour for the movie. The New York Times came out, and he’s reading the review. He handed it to me and said, “This is the best review we’ve ever gotten. Look.” And I’m reading the review of Some Kind of Wonderful. At the bottom it said, “Directed by John Hughes.” I was like, “Uh-oh.”

Filmmaker: That’s hilarious. You know though, I’ve always been a little jealous of guys like you who got opportunities like what Hughes gave you on Pretty in Pink. You got to do a well-resourced studio movie that was personal and an audience favorite right out of the gate. What was your directing experience prior to that?

Deutch: Well, I did theater. I was in a workshop at the Ensemble Studio Theater where you direct a play. I did two one-act plays, but not that much. I’d done four or five music videos with guys like Billy Joel and Billy Idol. So no, not a lot. But I wouldn’t be jealous of me, because once you start out at that level, there’s no place to go but down. [laughs]

The universe I came from was the trailer universe, where I was working on trailers like Apocalypse Now for Coppola. Our company was working with Scorsese and Woody Allen, so I was dealing with that level of filmmaker and seeing their rough cuts all the time. It was a very elitist perch I was sitting on. Basically, I was spoiled. I didn’t know how fortunate I was to get a seven-million-dollar studio film, because I was dealing with guys like Coppola and Scorsese and Warren Beatty and Robert Redford every day—I thought the way they were treated was how all directors got treated! Now I realize how wrong I was, and how lucky I was to get that kind of a break.

Jim Hemphill is a filmmaker and film historian based in Los Angeles. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.