Back to selection

Back to selection

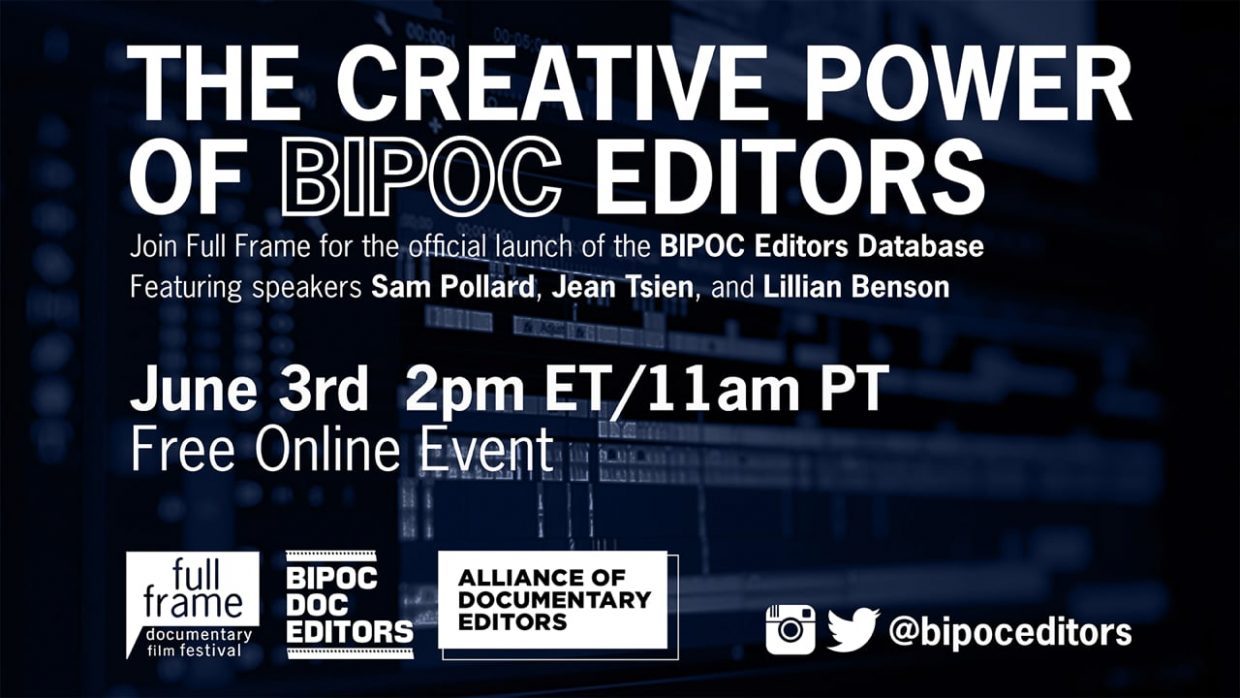

Full Frame Documentary Film Festival Presents “The Creative Power of BIPOC Editors”

“If I could log in right now I would,” Dawn Porter raved in one of the many enthusiastic testimonials sprinkled throughout Full Frame’s engaging “The Creative Power of BIPOC Editors,” an online launch/celebration of the BIPOC Documentary Editors Database. Expertly edited (surprise surprise), the swift-moving event (approximately an hour long) took place on June 3rd but is still well worth checking out. Whether you’re a veteran producer looking to hire beyond the usual (white) suspects or a student just beginning to build your reel, this database instruction manual/guide to best BIPOC hiring practices/panel discussion/showcase of the diversity of BIPOC work (completely forgot that Jason Pollard edited Dylan Bank and Daniel DiMauro’s Get Me Roger Stone) is jam-packed with stellar advice. (Not to mention entertainment. The “Editor Habits” segment includes a breakdown of “Must-Have Snacks”: “Does coffee count as a snack?” “Cheetos with chopsticks – otherwise your keyboard gets dirty.”)

Highlights included three featured speakers, all of whom have been cutting for decades (while racking up too many awards to mention). And all could speak to both their own personal experience as the only BIPOC person in the editing room, and as to why it’s crucial for the industry – and society at large – that it not stay that (87% white!) way.

Starting things off with opening remarks was Sam Pollard, who was introduced by longtime editor Sonia Gonzalez-Martinez – his apprentice all the way back on Spike Lee’s Jungle Fever. Having been in the business for over four decades, Pollard was quick to note that though he was usually the only African American in every room, his relationship with Black mentors – most especially St. Clair Bourne – inspired not only his work but also his belief in the necessity of bringing those from marginalized communities up the ladder with you. Indeed, the critically acclaimed editor (and director-producer-screenwriter) described it as a “responsibility” to get BIPOC into the editing room. And he strongly felt that because directors and producers hire who they know – i.e., other white people – the BIPOC Documentary Editors Database would be a crucial tool “to expand their landscape.”

The second speaker to address the virtual audience, Jean Tsien, can, according to Roger Ross Williams, “cut right to the chase.” Tsien, who immigrated from Taiwan in the early ’70s and got her start as Larry Silver’s associate editor, stressed that “No jobs are too small to take.” She urged aspiring cutters to attend film festivals, screenings, parties – whatever and wherever – to make connections. Tsien also disclosed a touching anecdote from early on in her career, when her fear of public speaking caused her to turn down the chance to advise at the Sundance Edit & Story Lab. To this day it’s one of her biggest regrets – not for her personally, but because she missed the opportunity to represent her Asian American community. And when she was recently asked to recommend an Asian American for an assistant editor gig? Her immediate response was, “Why not an Asian American editor?” “Don’t treat us as window dressing to meet your diversity quotas,” she added, calling out the unconscionably white male industry. “BIPOC editors bring a perspective that you don’t have.” Winding down her talk, she closed with the hope that all BIPOC editors, including the undocumented, would be inspired by her words to keep pursuing their dreams.

Rounding out the editing triad was the elder stateswoman of the panel, Lillian Benson, who gave the final keynote. The first African American woman invited to join ACE (in 1991 – WTF?) and the editor behind Eyes on the Prize and Maya Angelou And Still I Rise (among her 82 IMDb credits) began by asking, “Can we really tell any story in a complete authentic way if our crews and our editing rooms look like America of the 1950s?” Her foremost suggestion for improving cutting rooms? Be proactive about mentoring and definitely don’t leave this task to the BIPOC professionals, who’ve been going it alone for decades.

She also urged those on the higher rungs to be proactive about feedback. “Don’t just tell us the bad stuff, tell us the good stuff too.” Everyone needs to take it upon themselves to be the one to promote BIPOC crew. Benson also felt it crucial to dispel “industry myths that are actually lies.” To that end, she ran down a comprehensive list of the most egregious: “White equals good.” “People of color are never competent enough.” “An “objective” outsider has a more valid opinion than someone who has lived the experience.” People who believe these lies unfairly hold BIPOC editors to a higher standard than their white counterparts.

That said, Benson also recognized that there are often consequences to speaking up for BIPOC regardless of one’s race – “that retaliation is real.” She noted that history tells us that it was illegal to teach enslaved people to read or write, and that for white people who broke the law the fine was $2,842-$5,684. But for an enslaved person helping another to achieve literacy? That resulted in 39 lashes on a bare back. In other words, there are different penalties for the same “crime.” White allies indeed may suffer alongside those they support – but they do not suffer the same.

Concluding her address, the veteran editor brought up something a friend once told her, “Do not forget the bridge that brought you across to the other side.” She cited Eyes on the Prize director Jackie Shearer, who never forgot. And who she never forgot. Shearer’s honest and heartfelt affirmation, “You have no idea how good you are,” early on in her career had changed her life. Then she stated simply, “We should all lead with love.”’

The Creative Power of BIPOC Editors from Full Frame Documentary Film Fest on Vimeo.