Back to selection

Back to selection

Remembering Melvin Van Peebles, 1932 – 2021

Melvin Van Peebles (Photo: Richard Koek)

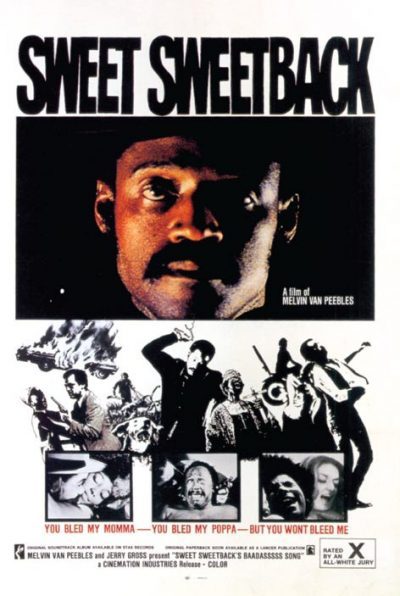

Melvin Van Peebles (Photo: Richard Koek) Melvin Van Peebles, revolutionary independent filmmaker whose credits include Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, Watermelon Man and La Permission, died Tuesday in Manhattan. He was 89. On this sad occasion we’re reprinting Brandon Harris’s profile of Van Peebles from Filmmaker‘s Fall, 2008 issue.

It isn’t the first thing you notice when you walk into Melvin Van Peebles’s Columbus Circle South digs, but very few items within his intimate, eclectically appointed apartment — one that sports the back end of a VW bus jutting out of one parlor wall and a giant sculpture of a hot dog near the window — speak more forcefully to the man’s nature than the large chest pin which sits clasped to the long stem of a floor lamp in his blue-painted living room. In black letters the word “whining” appears within a red circle, a slash running through its center.

A singular figure in the American cinema — and the American culture industry in general — it’s easy to marvel over the sheer scope of Melvin Van Peebles’s half century of creative work, for one finds within it so many triumphs and achievements, peculiarities and cautionary tales. Certainly in the figure of Van Peebles, the iconoclastic filmmaker, Parisian novelist, memoirist, reporter, Tony award-nominated playwright, teacher, musician, stockbroker and these days, graphic novelist, we are faced with someone whose work has at times been both seminal and forgotten, whose oeuvre is ripe with contradictory and fascinating details, whose contribution to American filmic discourse is both significant and elusive.

A man who shirks off comfortable distinctions and categorizations is not particularly easy to get to the bottom of. At 75, speaking briskly as he attends to his various hobbies, his full beard having long gone gray, hat and glasses offsetting a pink tank top with matching socks and suspenders, cigar dangling precariously from his mouth, Van Peebles strikes you as that rare man who having reached the twilight of his life is fully at peace with himself and his achievements. He’s spent a lifetime of bursting barriers and not taking “no” for an answer. It seems he’s satisfied with what he’s done, couldn’t care less about what he hasn’t and has a wiry energy in his small frame that could outlast a man half his age. When asked to approximate something akin to a personal philosophy, he replied in his typical take-no-prisoners style in between cigar puffs: “Don’t write a check with your mouth that your ass can’t cash.”

The man who at various intervals has claimed to “invent” hip-hop and the movie soundtrack as a separately sold album has never been known to be shy or unassuming in his public pronouncements. Although he’s not known as a paragon of humility, he has a self-deprecating streak that sneaks up on you and seems as important a part of his makeup as any. He isn’t one to complain or to tread deeply into self-analysis. When asked about the differences of working in theater and film and how the mediums differ and inform one another, the man who occasionally teaches a semester of film at Fordham says, “I don’t know. You’re talking to students — what the fuck do I know, man? Hmm? You’ve got a board and you gotta stand there, you know what I mean, man? That’s the way. I’m not really very much on the analysis of the stuff. I’m working in the post office and I’m talking to people and they started jockeying to sit next to me and I started talking and giving them my stories that I made up — what could be more uncomplicated than that? What am I gonna say? ‘Badebadebadeba?’”

The aesthetic populism of that statement, although visible in the accessibility of his storytelling in all seven of his features, which include La Permission (1967), Watermelon Man (1970), Don’t Play Us Cheap (1974), Identity Crisis (1989), Bellyful (2000) and his newest, Confessionsofa Ex-Doofus-ItchyFooted Mutha (2008), is most stirringly evident in the film he is most widely known and revered for, the 500-pound powder keg that is his 1970’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song. (The Museum of Modern Art celebrated Van Peebles work in October when they screened a newly restored print of Sweetback as the opening film of their 6th MoMA International Festival of Film Preservation. In December, they plan to screen La Premission and Confessionsofa Ex-Doofus-ItchyFooted Mutha in honor of his Gotham Award Tribute.)

While all the films reveal Van Peebles’s central obsessions and stylistic preoccupations as a director — his vigorous if unrefined mise en scene, a fascination with mirrors and a reliance on superimposition, violent sound editing and politically, sexually and racially transformative moments within his often-flat narratives — his most remarkable creative achievement may be his versatile ability to transfigure his filmmaking practice to the zeitgeist and dominant aesthetic mode of the milieu in which he is working. La Permission, for example, is informed by the French Nouvelle Vague, while Watermelon Man is informed by the aesthetic of 1960’s mainstream American studio comedies. Sweetback, however, is the film that changed American independent cinema forever and is the apotheosis of his work.Van Peebles took a circuitous route to filmmaking. Born and raised in a middle-class black suburb of Chicago, he attended Ohio Wesleyan University where he studied painting and astronomy. After a tour as a jet bomber in the U.S. Air Force, he began making films in the Bay Area in the late ’50s. A few of his shorts caught the attention of Amos Vogel, who co-founded the New York Film Festival and wrote the 1974 book Film as a Subversive Art. Vogel showed the films at a cinematheque in Paris and invited Van Peebles to join him. He did, and quickly found himself homeless in Paris without means to get back to the States.

He learned French piecemeal and eventually picked up enough to become a journalist. He was a crime reporter in Paris before becoming the editor of Hari-Kiri, a French humor magazine. Still wanting to pursue cinema, he soon found his in. “I discovered there was a French law that said they’d pay a French writer to get a temporary director’s card to get his own stories to the screen. You just had to write five novels in French. So I did and that’s how I got my director’s card.”

At 35, Van Peebles directed La Permission (The Story of a Three Day Pass) from a script based on his own original story about a black GI’s forbidden weekend romance with a French woman. He became the first African-American director to make a narrative feature since Oscar Micheaux’s The Betrayal (1948), a gap of just more than 20 years between each films’ American premiere. When the film had its premiere at the 1967 San Francisco Film Festival, Van Peebles was the only French representative. Other than Albert Johnson, an old friend of Van Peebles from his early Bay Area days, none of the programming or administrative staff knew ahead of time that he was black. They were shocked when he got off the plane, issuing a confused but warm welcome for the iconoclast upon his return to the city where he had first began making films. Regardless, he already had his mind set on making a film that addressed America’s most historically divisive questions head on.

The film was thought up (despite his son Mario’s more sanitized version of events in Baadasssss!, a 2004 docudrama about Sweetback’s production) during a masturbatory interlude on the side of a California freeway. Heavily influenced by both black nationalism and Los Angeles psychedelia, Sweetback features amazing optical work by experimental filmmaker Pat O’Neill and was financed in part by Bill Cosby. Starring its director (and his son) in a nearly silent performance, the story follows a sex worker, raised in the same brothel where he plies his trade, who earns a reputation and moniker for his skills in the sack. He is given over to the police by his employer as a patsy in exchange for the police turning a blind eye to the South L.A. whorehouse where Sweetback lives. He is taken in along with a black revolutionary who is mercilessly beaten by the cops following a civil rights protest. Sweetback, standing idly by at first, kills the police officers and saves the young man, but soon they are both being sought by corrupt law-enforcement officials, resulting in both Sweetback’s sociopolitical awakening and his attempt to flee, mostly on foot, to Mexico. With more than a little bit of help from the “black community,” which a title in the opening credit sequence claims is the true “star” of the film, he gets there, but with a promise to return to collect some dues, liberal integrationists be damned.

The film premiered at Detroit’s Grand Circus Theatre on March 31, 1971, with Van Peebles essentially self-distributing with the help of a company that had specialized in porno films after he was laughed out of every distributor’s office in Hollywood with his X-rated black revolutionary movie.Through Van Peebles’s ingenious DIY distribution and marketing techniques, employing both the local chapter of the Black Panthers and the formidable community sounding board of Black radio to spread the word, Sweetback became the highest grossing American independent film to date, pulling in $10,000,000 before its run ended. It also set off a seemingly never-ending debate about representations of blacks in American cinema, often along class and ideological lines.

Huey Newton of the Black Panthers publicly lauded the film, calling it in his essay He Won’t Bleed Me: A Revolutionary Analysis of Sweet Sweetbacks’s Badasssss Song “the first truly revolutionary Black film made and presented to us by a Black man,” before going on to say that it “presents the need for unity among all the members and institutions within the community of victims.” Publications of the black middle class, like Ebony magazine, largely denounced the film. In his 1971 essay for that publication, “The Emancipation Orgasm: Sweetback in Wonderland,” Lerone Bennett argues that Sweetback defines “blackness” in reaction to the black bourgeois ideal of the ever-striving, upright Negro (read Sidney Poitier), saying, “Some men foolishly identify the black aesthetic with empty bellies and big-bottomed prostitutes,” before going on to deride the gender politics of the film, one in which young Sweetback, played by young Mario, is deflowered at 11 years old by a prostitute. Clayton Riley, writing in The New York Times, viewed the film more favorably, calling Van Peebles’s Sweetback character “the ultimate sexualist in whose seemingly vacant eyes and unrevealing mouth are written the protocols of American domestic colonialism.” Later he would write, “Sweetback, the profane sexual athlete and fugitive, is based on a reality that is Black. We may not want him to exist but he does.”

The film spurred Hollywood to start making films for the hungry black urban audiences who made up nearly 30 percent of movie-going public at the time, as whites, fleeing cities in the wake of urban uprisings across the country, ceded popular urban movie houses to blacks in inner cities. Released just as the tumult of the 1960s was drawing to a close and in many ways the quintessential “black power” film, it was simply too hot for Hollywood to handle, at least until they found ways to homogenize and depoliticize the content and repackage the themes of Sweetback in the 60 or so blaxploitation films of the ensuing years.

For Van Peebles, little of this matters now. He’s content with his work, not too interested in the various readings of the film by academics and cultural commentators and happy that he opened the door for other African Americans to pursue their cinematic dreams. “Well, I think every black filmmaker, everybody wants it to be their revolution, their way,” he says. “I just wanted to get the chance. They’ll work it out. They’ll get it together.”