Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Wanted to Target an Audience Not Necessarily Interested in the Royal Family”: Editors Jinx Godfrey and Daniel Lapira on The Princess

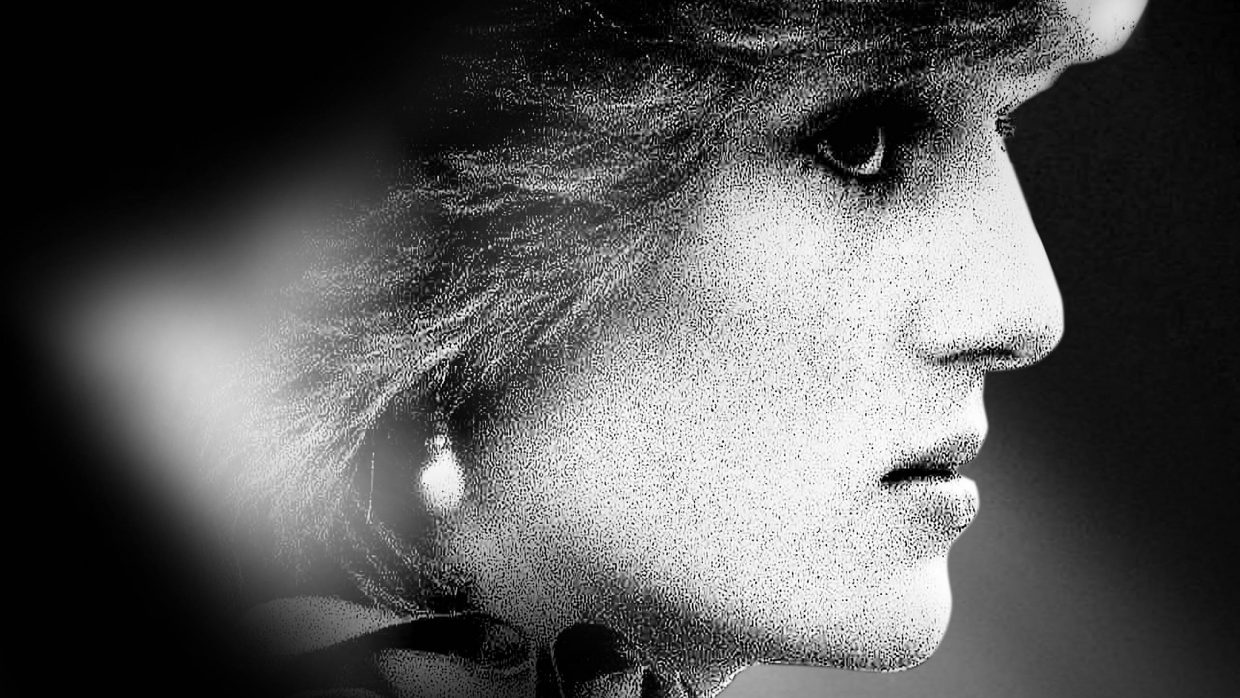

A still from The Princess by Ed Perkins. (Photo: Kent Gavin)

A still from The Princess by Ed Perkins. (Photo: Kent Gavin) From the beginning, director Ed Perkins knew he wanted to tell Princess Diana’s story without any retrospective interviews and instead rely purely on archival material. That’s a rich archive, consisting of thousands of hours of footage, meaning the editors would need to choose among countless potential approaches or narrative threads. Below, editors Jinx Godfrey and Daniel Lapira discuss what drew them to the film and how they managed to whittle thousands of hours of footage into a 104-minute feature film.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Godfrey: I previously worked with Lightbox producer Simon Chinn on documentaries—Man on Wire and Project Nim. In 2020, he approached me about working on The Princess. When he explained it would be an archive-only film, with no retrospective interviews at all, my interest was piqued. I knew the director Ed Perkins and I liked him and his work. Also, I was reassured by the backing of HBO and Sky. I could be part of a “different” film about Diana, a subject matter that I was not enamored with, a film that hopefully people like myself would watch and enjoy. It was to be a “remote” edit which, at the time, worked very well for me since COVID was wreaking havoc amongst productions. This job seemed a secure way to navigate 2021.

These days I always try to include an assembly editor/co-editor in my team. I value cutting room collaboration highly; I like to encourage freedom to express ideas and opinions about the edit, be it from a trainee, assistant or editor.

For The Princess I enlisted the help of Daniel Lapira, with whom I’d worked on a previous project. Daniel is from Malta, and I knew he would enhance our understanding of the story by being less familiar with it, as well as by being a very talented editor. We had an assistant editor, Sam Calverly, who worked with us as a trainee on our previous film. A small team, and we all worked remotely from home.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Lapira: Acutely aware of the multitude of documentaries about Diana, we were wary of the type of film The Princess could be. We wanted to tell the story differently. We knew the roads we didn’t want to take from the get-go. Ed [Perkins] had a very strong ideas about how the people’s perspective had to be an integral part of the film and of the symbiotic relationship between the people, Diana and the royal family and between Diana and the media. It’s no secret that documentaries are made in the cutting room, and this film was no different. The main advantage on this film was that we had each other; the collaboration between Jinx and myself was invaluable. We wanted to keep it as simple as possible, tell a human story, one that could be relatable, and an emotional drama that unfolded naturally, progressing without being overly manipulative. Addition by subtraction, exploiting nuances and subtleties. We wanted to target an audience not necessarily interested in the royal family but nevertheless curious about another human story, her story.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Godfrey: Ed would select the archive into long select rolls, between 8-12 hours, and we would cut these down into workable scenes. Once we had a 4-hour assembly of the entire film, we began to cut story beats we felt were superfluous or repetitive. We shaped it like a drama, with a focus on the emotional arcs of the main characters, Diana and Charles. Once the film was at a reasonable length and internal feedback was becoming less instructive we sent the film to a handful of friends, other editors, industry people, etc. to watch and provide feedback. All this was invaluable for taking the film to the next level.

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Lapira: Hard work does pay off, but I never underestimated the power and importance of meeting and networking with the right people. I also think that your personality plays a very important role by attracting the right collaborators, the ones you would like to be surrounded with, which also really helps the process. Along the way I must admit that I was lucky enough to meet very generous people in the industry who were willing to help, teach and share their craft and never-ending wealth of experience and expertise.

After spending six years in television as an editor and live programs director/vision mixer, I felt I needed to break away from the local scene to move onto doing what I really loved—editing feature films. I’m originally from Malta, where I managed to gain invaluable experience working my way up through the various studio and independent film productions—which were plentiful thanks to the locations, filming tanks and, of course, the tax rebates. Due to this influx of productions, and after assisting very talented and established editors, I managed to shape and enhance my craft and skills to become the editor I am today. I really love the collaboration process with likeminded, passionate people, and I always strive to get the very best out of what is presented to me, approaching every project with an open mind and a commitment to enjoy the process.

With regards to influences, I don’t think I can really pinpoint. There are so many great film editors and directors out there, and the culmination of all the people I had the privilege to collaborate with really helped shape my approach. Obviously there are those unforgettable experiences that stand out, for example working on Spielberg’s Munich. What better film school could you possibly attend other than witnessing Steven articulate an approach to a scene with his lifetime collaborator and editor, Michael Khan?

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Godfrey: We edited on Avid, a system we’re both comfortable with, and we didn’t consider cutting on anything else. Initially we were asked to edit on a cloud-based system so that we could share media, but we rejected this and opted to stay on hard drives. We would download media from Lucid onto our hard drives almost daily since archive was flying through the door all the time. We were able to email each other bins and cuts in order to discuss edits before involving the director.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Godfrey: It’s impossible to answer this really! The toughest scenes to edit were the ones which were “thin” on footage. In these instances we’d have to think very creatively, almost laterally, in order to find a way through. When we had a wealth of vérité footage, the scenes cut together more straightforwardly, but the mountains of material for these scenes was overwhelming at times.

Unusually, we leaned heavily on music to help us interpret the emotion of a scene. I was unused to doing this and always prefer not to use music as an emotional crutch, but this film almost required us to do so. We didn’t have the luxury of our main characters displaying emotion in what they said or the way we read their expressions; most of the time our characters were stoical and impenetrable. We needed to help the audience understand what to feel. We only discovered this quite late in the edit since our instincts were to be more ambiguous with what the music was doing. Once we understood how the music could help us, we discovered a more emotional way through.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Godfrey: Despite the disadvantage of telling a familiar story that is universally well known, I think this film does the job of telling the story differently. Footage watched a thousand times somehow feels new and unseen. Without retrospective interviews telling you what’s happening, the audience is forced to scrutinize, to immerse and experience, as opposed to being having things spelled out. Yes, you have to work a bit harder, but if you go with it, I think, by the end, you might feel differently than you expect.