Back to selection

Back to selection

“At the Root of This Rivalry Is a Historical Conflict Between Mexican Nationals and Mexican-Americans”: Editor Luis Alvarez y Alvarez on La Guerra Civil

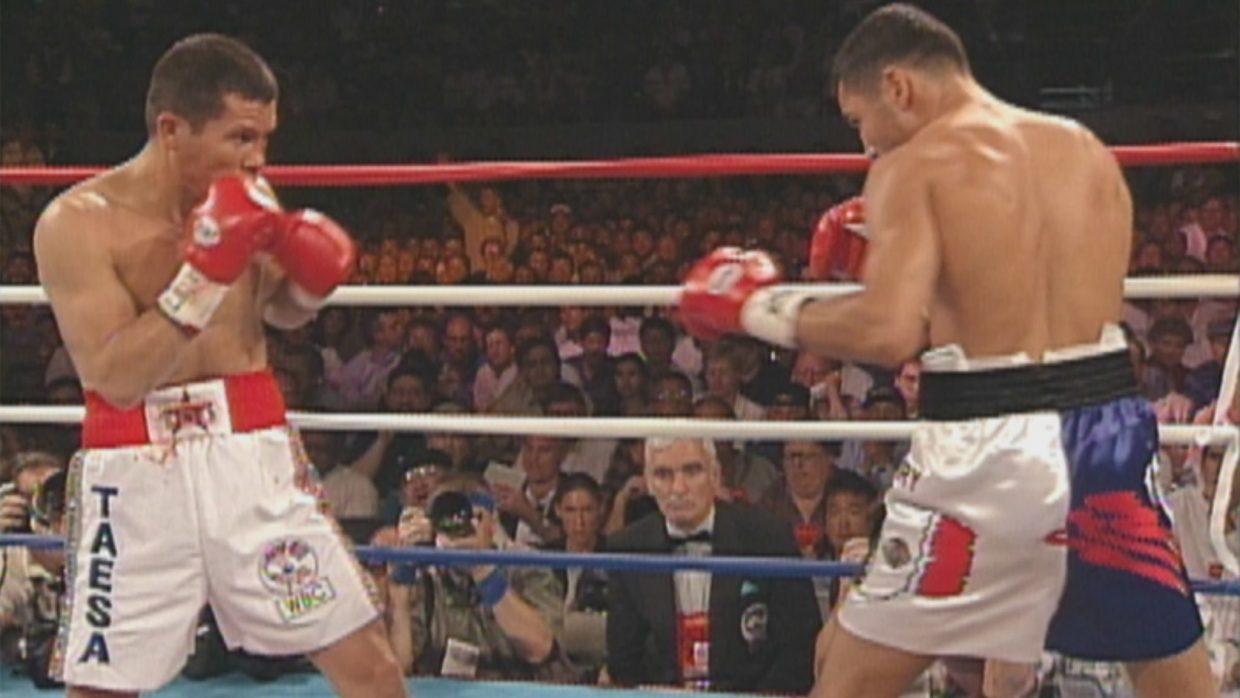

Oscar de la Hoya and Julio César Chávez in La Guerra Civil by Eva Longoria Bastón.

Oscar de la Hoya and Julio César Chávez in La Guerra Civil by Eva Longoria Bastón. Julio César Chávez and Oscar de la Hoya were once two of the biggest names in boxing, and their 1996 bout dubbed “Ultimate Glory” was a flashpoint for the divide between Mexican-Americans and Mexican nationals. Mixing archival footage with interviews of the boxers themselves, <i>La Guerra Civil</i> examines the bout, the rivalry and its cultural dimension. Editor Luis Alvarez y Alvarez discusses his memories of the fight and how the filmmakers were able to recapture and illuminate one of the defining sports moments of the 1990s.

Filmmaker: How and why did you wind up being the editor of your film? What were the factors and attributes that led to your being hired for this job?

Alvarez: I had previously worked with producer Bernardo Ruiz on a documentary series. He thought of me for editing La Guerra Civil. The film is about these two legendary boxers and how their “Ultimate Glory” bouts divided the Mexican community in the US. At the root of this rivalry is a historical conflict between Mexican nationals and Mexican-Americans, which is something that many Americans are not too familiar with. Even though we are all of Mexican origin, the generations that grow up in the US and the Mexicans reared in Mexico have distinct cultures and don’t always get along. I grew up in Mexico City and Tijuana and after college I moved to the US, where I’ve now lived half my life. I’ve been exposed to the cultures and the conflicts we touch on in the film. I am aware of the cultural nuances and the sentiments on both sides. My father’s family were big boxing fans, so I grew up watching and loving the sport. Julio César Chávez became a boxing star in Tijuana in the late ’80s, at the time I was living there finishing high school, so I knew very well his career and his cultural significance. I believe these factors, in addition to my experience editing documentaries, made me a natural choice when it was time for director Eva Longoria to pick an editor.

Filmmaker: In terms of advancing your film from its earliest assembly to your final cut, what were your goals as an editor? What elements of the film did you want to enhance, or preserve, or tease out or totally reshape?

Alvarez: The film’s scope was ambitious. We were covering the biographies of two legendary boxers, the events leading to their bouts and the cultural divide that occurred. There was such a wealth of material. As I was assembling I felt that we could easily make a very entertaining three part series, something in the format of The Last Dance, but we were making a feature and breaking it down into episodes was not an option.

Many of Julio and Oscar’s fights were epic, but there was not time to include all the highlights. I had to boil many sections down to their core but was always aiming to preserve the sense of drama and make room for the boxers to express the emotions they were going through.

Filmmaker: How did you achieve these goals? What types of editing techniques, or processes, or feedback screenings allowed this work to occur?

Alvarez: We had great interviews, so by combining first hand voices with short potent archival sequences I believe we were able to get to very distilled story elements that spoke truth for each historical moment we touch on.

When I started editing, right away I could tell that playing through a biography or the build up to the 1996 fight in full wouldn’t be as interesting as moving all the story lines together. This meant having to find the right moment to go from one story line to the other, which also meant moving back and forth in time. The challenge here was maintaining clarity and keeping the audience oriented. I initially relied on dates appearing on screen to mark the transitions in time. Those worked for me, but when I shared cuts with Eva and our producers they would ask for more clarity in these transitions. Something that helped in this case is that a number of our interviews took place after the cut was already in an advanced editing stage. This allowed us to prepare questions to get lines from interviewees that would signpost the transitions.

For me, “feeling the room” during a feedback screening is the best way to gauge what works and what doesn’t in a film. That was not an option working in isolation due to the pandemic, so we had to rely on sharing cuts and meeting on Zoom to discuss notes. I feel that in the case of La Guerra Civil we flew by instruments, and by that I mean we had to trust that the collaboration and feedback within our team, led by Eva, would hone in the storytelling. I can’t wait to see the film with a live audience!

Filmmaker: As an editor, how did you come up in the business, and what influences have affected your work?

Alvarez: I moved to the San Francisco Bay Area after graduating from college in Mexico with a business degree, but I was not interested in a business career. I loved films, but filmmaking seemed very distant at that point. I was very lucky to end up meeting mentors that opened doors for me. That and taking a bit of risk to move forward have been the keys.

In the Bay Area I first interned and started assisting in independent documentaries. Shirley Thompson, one of the editors I was assisting at the time, referred me to Pixar, a (then) small studio making animated films. I consider Pixar my film school. The tech was cutting edge, many of the film people working there came from the Francis Coppola and George Lucas neighboring outposts and the story and art people were the next generation out of the CalArts/Disney stable, all in an early Silicon Valley-type incubator. It was so much fun. As an assistant editor, I sat through numerous editorial and story meetings that made many of the now classic scenes in Toy Story 2, Finding Nemo and Monsters Inc. That time really taught me how to craft a story and characters.

But I never saw myself just working in animation. So, following the advice of editor Edie Ichioka, another mentor, I moved to Los Angeles to work in live action films. My first job assisting turned into my first editing credit, and in it I met editor Pietro Scalia. Pietro then brought me to cut The 11th Hour, a film that Leonardo DiCaprio was producing, and from then on I’ve been editing docs. My time in the cutting room with Pietro Scalia was also instrumental in my education as an editor. He is a big influence.

Filmmaker: What editing system did you use, and why?

Alvarez: We cut La Guerra Civil on Avid Media Composer. It’s my preferred tool. I’ve used it for so long that it’s the one that comes most natural to me. I like the feel of a timeline that stays put. I find other software too wobbly. In the Avid, the script tool is super handy for looking up lines in transcripts.

Filmmaker: What was the most difficult scene to cut and why? And how did you do it?

Alvarez: The transitions between the boxers’ biographical story lines and the buildup to the ‘96 fight I mentioned above were tricky. Another challenge was building sections of the early lives of both boxers. There was very little material of that time. There was nothing of Julio’s childhood and just a few photos in bad shape for Oscar. I had to get creative on how to depict visually these stages of their lives. I also have to give credit here to our Producer Andrea Córdoba, who wore many hats, and one was the archival producer’s. She kept reaching out to the boxers’ families and other sources to acquire material. Her tenacity really paid off.

Filmmaker: Finally, now that the process is over, what new meanings has the film taken on for you? What did you discover in the footage that you might not have seen initially, and how does your final understanding of the film differ from the understanding that you began with?

Alvarez: Boxers are amazing athletes, and the really good ones are very smart. They are sharp and really good with strategy. When you have smarts and charisma you get a phenomenon like Julio César Chávez. I spent so many hours watching his interviews, and often I would find myself with a big smile on my face. He wears his heart on his sleeve. This made me realize why he’s so loved.

I also became much more aware of the significance of Oscar de la Hoya for a generation of Mexican-Americans. They saw themselves represented in him—something not common at the time. As children of immigrants, often facing contempt in their adopted country, their seeing Oscar win a gold medal gave them an elusive sense of pride. Oscar was also a crossover hit probably not seen since Desi Arnaz. He also made women get interested in boxing because he was as good looking as he was super talented in the ring.

Something else worth mentioning is that at the root of the cultural conflict in the film there is this idea of being “Mexican enough.” Oscar really tried to prove that he was. Julio mocked him about it. That fed their rivalry. But if you think about it, it’s kind of a schoolyard type of mocking that works as timber to start a fight. But in the end it’s not really an issue. There was nothing to prove. They are both Mexican in their own way.