Back to selection

Back to selection

Speculations

by Joanne McNeil

Beyond the Third Act: Everest Pipkin’s Cinema-Inspired Tabletop RPG World Ending Game

Courtesy of Everest Pipkin

Courtesy of Everest Pipkin “Endings are very hard,” said Everest Pipkin. “It’s one of the most difficult things about making anything, and only gets harder when you are collaboratively telling a story with lots of people.”

Speaking via video chat from their home in southern New Mexico, Pipkin, an artist and game designer, recently released World Ending Game, a tabletop “falling-action game” designed for players to bring existing campaigns to a close. Say you’re part of a weekly group playing Dungeons & Dragons and everyone is ready to move on. Your party can wrap things up and bring your existing characters — the druid, cleric and ranger, say—into a new role-playing context: the film set Pipkin developed for this project.

The game is inspired by the endings of films and even mimics filmmaking techniques. There’s an illustrated list of camera directions in the back of its rule book for the gamemaster to incorporate in their performance as the “director” of this production. The GM guides the story with verbal commands like “zoom in” or “fade out” and might even call for another take or decide to leave a scene on the cutting room floor. The characters are the actors. While somewhat complicated to explain, it’s a clever and practical setup: Narrative films, unlike games, have a definitive end. The experience, as the book explains, is meant to be reminiscent of the “feeling of emerging from a movie theater into a dark parking lot, under the stars.”

Instead of leaving loose threads or causing the confusion that can happen when a campaign is finishing up, World Ending Game firmly establishes closure for its players. As Pipkin explained, in long-running campaigns, groups find “sessions become less frequent, as people move away and have children and get new partners and have falling outs, until the story that you’ve been telling for years or sometimes decades just dwindles.” But even in relatively shorter campaigns, with a traditional game climax—a big heist or battle or a dragon slain—there is often no process afterward to disembark from the world after all that excitement. Unless an ending is expressly written for the game, players finish up feeling like, as Pipkin put it, “OK. Well, goodbye.”

Pipkin grew up playing D&D, LARPs and forum games. Their art tends to engage with code and generative elements, and the artist is likewise fascinated with the “textual element” of gameplay. There’s a “combinatory logic to games and tabletop games, especially,” they said. The artist’s previous tabletop game project, The Ground Itself (2019), is a single-session world-building game. In a sense, World Ending Game is its bookend companion. While The Ground Itself can be played as a standalone experience, groups often use the game to establish history, ecologies and broader context for a world before jumping into D&D or another tabletop game. It was in creating The Ground Itself that Pipkin found inspiration for World Ending Game. They realized there were a lot of games like it—making up a new place, imagining a new world—but “not so much walking away from it. I wondered what a game like that would even look like.”

Certain prompts in the game might bring specific film classics to mind, like Dr. Strangelove when playing the “The Apocalypse” ending, in which the game ends as “all goes up in flames,” or Charlie And the Chocolate Factory for “Passing the Torch,” which involves a character passing on something important to them—a “secret, a story, an impulse, or a mission”—to another character. Ideas for these endings came out of Pipkin’s early research reviewing the final 15 minutes of action from hundreds of scripts and plot summaries. (It’s territory also explored in JP LeBreton’s Mastodon bot “As the Film Ends,” which, using films on Wikipedia as the corpus, posts the final lines of film plot summaries. Entries range from the instantly recognizable—“Realizing that she has lost everything, Anna walks onto the railway tracks and commits suicide by letting the train hit her”—to the obliquely universal—“She bursts into tears and embraces him, and the two reunite.”) Pipkin began categorizing types of endings from the “kiss in the rain” to the “ride into the sunset.” These endings, which are not necessarily genre specific, will feel familiar to filmgoers.

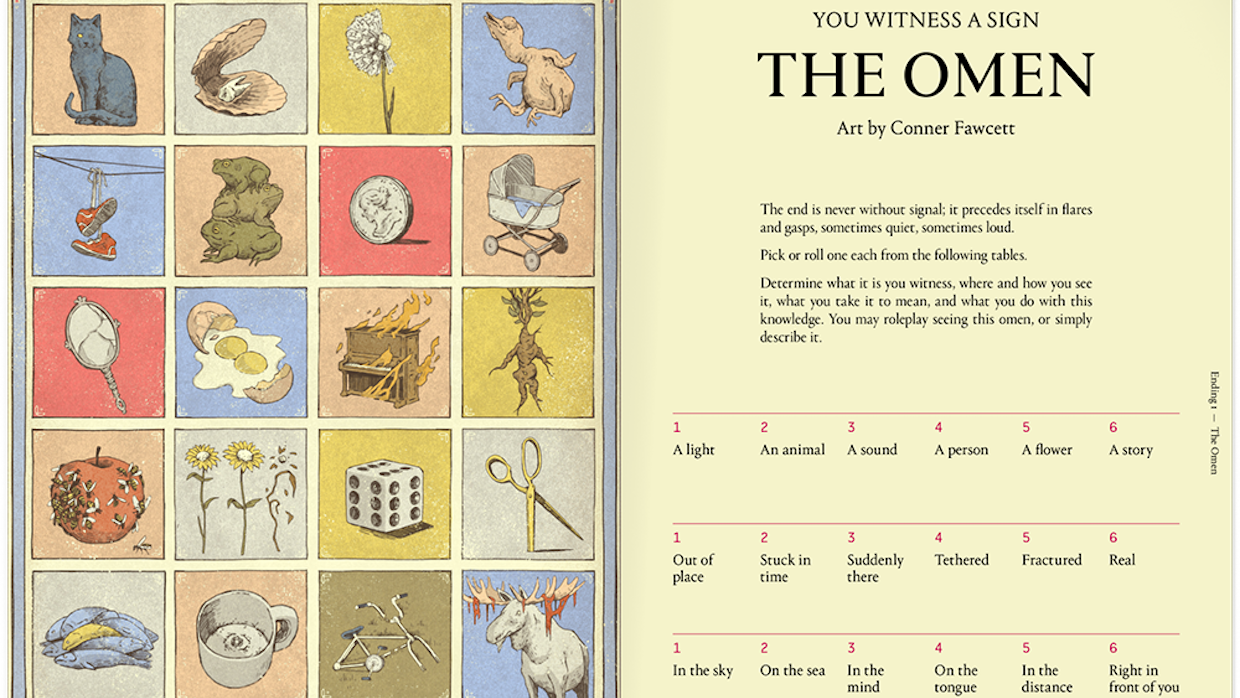

World Ending Game has a stunning book, designed by Andy Pressman, that features original art from 25 commissioned artists. Among other possible endings is “The Revision,” in which a character is asked to take an event that happened over the course of the campaign and envision how it is retold and remembered years later through art or personal memories. The player would then narrate an example, perhaps a theater performance that reenacts the event or a nursery rhyme that school children sing, sealing the event into legend. Or they might imagine how their character retells this event to entertain a crowd: What details are exaggerated, and what is played up for a laugh? The companion illustration, by Sophia Foster-Dimino, shows young people in a museum looking up at a tapestry of a knight battling a fire-breathing dragon. Other endings, like “The Anime Music Video” and “Karaoke Bar” (an expansively defined setting that could be the dance floor at a wedding or a lullaby sung “quietly, in the dark”), go out with a song. Because each character is to play as the lead actor in at least one scene, groups will experience multiple endings before the ultimate finish. The game ends—for good—with a cut to the final shot.

One of the groups that play-tested World Ending Game began its campaign when the members were freshmen in college. They are now in their 30s with kids and live great distances apart. Pipkin’s game was a way to say goodbye—not just to the campaign, but to the character each has played over the years. There’s a personal element to this conclusion, akin to an actor getting into costume for one last performance in a long-running play or television series. “To carry one person around in you for five years, 10 years, and then to set up a life that they can live in and walk away is a pretty wild thing to do,” Pipkin said.

As one of the prompts from the “Ride into the Sunset” scenario says: “Your work here is done. What have you decided is finished?”