Back to selection

Back to selection

Editor Walter Murch on the Golden Ratio, Recreating a ’70s-era Editing Room and The Conversation

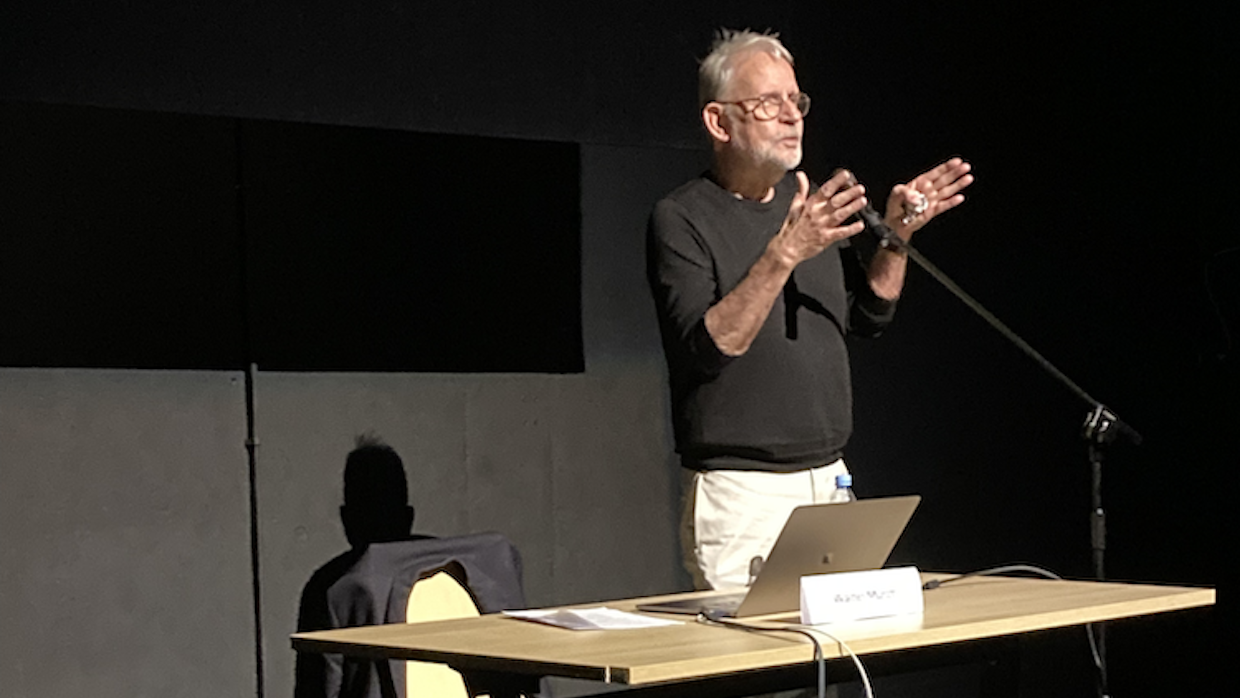

Photo by Daniel Eagan

Photo by Daniel Eagan Watching a documentary on film history, editor Walter Murch was struck by how different cinematographers tended to frame faces in close-ups similarly.

“I noticed something peculiar,” he said. “No matter what the film was, the eyes of performers in close-up seemed to float along the same line from shot to shot.”

Murch tested his theory by tying a string of knitting yarn across his television screen. Dividing measurements from above and below the line gave him 1.618, a number that represents phi, or the golden ratio. Further measurements of faces in close-ups—from the upper frame edges to hairlines, from chins to the bottoms of frames—resulted in more golden ratios.

Artists have known about the golden ratio for centuries. It also appears in nature, from seashells to the shapes of galaxies to how DNA spirals. On screen, “it’s as if the proportions of the face, hairline, eyes, chin, are echoed in the proportions of the resulting frame,” Murch explained. “It’s the visual equivalent of harmonic consonants in music. It’s like a dominant chord.”

During a presentation at the EnergaCAMERIMAGE in Toruń, Poland, Murch explored the golden ratio over the span of human history, from Neanderthal skeletons to AI-generated portraits, concentrating on how cinematographers have “intuitively” arrived at an unofficial standard for close-ups.

Murch’s findings figure into a book he is writing about editing. He is also working with filmmaker William Kentridge on a nine-episode series about “the process of creativity in the studio.” One of the cinema’s most respected editors and sound mixers, the Oscar-winning artist has worked on The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, The English Patient, and many others.

Murch spoke with Filmmaker following his Camerimage presentation.

Filmmaker: What prompted you to look into the golden ratio?

Murch: I was writing a chapter in my new book. I ask, “What does an editor do when presented with 8K overscanned images?” Because now the editor is responsible for choosing frames, in conjunction with the director, of course. But initially you have to come up with something. So what is a good frame when you do a close-up within an overscanned image? How do you decide what to do? One thing you can do if you’re trying to do a close-up is adjust it so the eyes are at that horizon. If you want to express an attitude, you can deviate from there if you want. Deviation is what makes art. But it’s a good place to start.

Filmmaker: How do cinematographers apply this idea?

Murch: They’re applying it instinctively, intuitively. It’s like how John Seale described composing close-ups. He said, “I try to make the face feel comfortable in the frame.” What I’m talking about is not prescriptive, it’s descriptive of something that’s already taking place. There’s no “golden ratio” line on the ground glass of a camera.

If the eyes of the actor in the close-up or medium close-up are above the golden ratio line, it tends to make that person have a looming or forceful presence. And if you diminish it, it, they are subtly being crushed by the empty space above their heads, and appear weaker. If you look at a photograph of Trump or somebody in a newspaper, if they want him to appear weaker, they will put his head down near the bottom of the frame to increase the horizon.

Filmmaker: I’ve spoken with cinematographers who are dismayed with 8K, especially in advertising. They’re trying to compose a frame, and will be told not to worry about it. They’re recording so much data that the client can decide what the frame will be later.

Murch: Yes, that was the origin of this whole idea. You can blame certain directors or clients, or you can decide it’s the fault of digital technology that enables that kind of thinking.

Filmmaker: Do you miss the old techniques?

Murch: I’m very glad I lived through them [laughs]. Last August we recreated an editing room circa 1972, so 50 years ago, for a series. Moviola, rewinds, synchronizers, bins, all that material. I convinced Mike Leigh, the British director, to give us the uncut files from his film Mr. Turner. We reverse-engineered those files and printed them on 35 millimeter and made a magnetic soundtrack for two scenes. Then treated those two scenes as dailies coming into the editing room.

My assistant Dan Ferrell and I recreated what happens in the editing room for the series. You have to sync everything up, this is how you do it. You have to project the dailies, this is how you do that. You code the dailies, wrap them up as individual shots, label them and put them in boxes. Then I edited them on the Moviola. We were wired for sound and kept talking to each other about what we were doing.

Filmmaker: You couldn’t even use a Steenbeck?

Murch: Well that was the point, to do it the way all films were edited up to 1969. We’re editing it now.

Filmmaker: What was it like working with that equipment?

Murch: It was fascinating. I hadn’t edited on a Moviola since 1977. Dan hadn’t worked on one since he was an assistant on Empire of the Sun. Nonetheless, we both immediately gravitated to it and knew exactly what to do, even though decades had passed.

It was exhausting because you’re on your feet and physically doing stuff all day long. You know, every cut you have to bring the splicer in and cut it.

Filmmaker: Was it a hot splice?

Murch: No, a tape splice. This was 50 years ago, not 70.

A big problem we had was finding a theater that could show double-system mag and picture. The producer of the show is linked to the Kubrick estate, so we went out to St. Albans to use his Steenbeck, which was of course in perfect working order. Mike Leigh came over, we threaded up the two scenes and watched them together on the Steenbeck.

Filmmaker: Was your work close?

Murch: What do you mean by close?

Filmmaker: Were you trying to duplicate the original film?

Murch: No, I was just trying to cut. I’d seen the film, but not for several months. So in editing, I was just responding to the material. Mike Leigh watched the two scenes cut together and said, “You used too much sailboat.” I answered, “Well, you shot it.” And Mike said, “I didn’t shoot it, that was the cameraman [Dick Pope]. He just shot it because it was there.”

And yet Timothy Spall, the actor who played Turner, spent some time looking out the window. In some of the wider shots you can see a sailboat outside the window. I cut to his point of view. It was just a shot that was there.

The two versions were not identical. It’s a dinner table scene. He started wide and moved in over the course of the scene to close-ups. Once he was in close-up, he stayed there. Because of the architecture of the scene, they talk about one thing and then spend some time looking out the window. When they change the subject, I cut to the wide shot and then moved in again. That was basically the only difference.

Filmmaker: I learned on that equipment, and it’s easy to romanticize the era, but that process was so difficult.

Murch: That’s the reason we shot this film, to document how difficult it was. If we had waited another ten years, there would be no way to do it. We were just able to assemble all of the machinery and equipment. The big crisis was the machine to print code numbers. At first we couldn’t find the pressure-sensitive heat tape that printed the numbers. Without that tape we couldn’t have done anything, because the only way you can maintain synch in that system is with those numbers.

Filmmaker: Do you think more about individual cuts when you are working with that equipment?

Murch: Perhaps. It depends on your personality and how seriously you take the work.

Filmmaker: One of the problems with editing today is too much cutting. It’s as if some editors don’t trust the material, or are trying to find it in an assembly.

Murch: I know very talented editors who make wonderful work, who start cutting without even looking at the dailies. They just plunge right in. That’s not temperamentally what I do [laughs]. I screen the dailies and I take very specific notes about everything so that I have it all in my head. Then I begin editing. That’s what I had to do back in the days of physical film, otherwise I would get completely lost. Digital editing does facilitate careless work. But there were badly cut films back in the days of celluloid.

Another problem now is the tendency of doing resets within the take. The director says, “Okay, action.” You’re rolling along. And then the director will go, 15 seconds into the shot, “Okay. Stop. Go back and say that line again. Only louder.” The actors have to stop and figure out where they were. In my opinion it’s a very destructive way to shoot.

Filmmaker: And difficult to log.

Murch: Yes, it is. It is.

Filmmaker: Before I go, I just want to repeat how seeing The Conversation changed my approach to looking at everything. It opened up all these possibilities of cinema that I had never really thought about before.

Murch: The last time we talked, I can’t remember if I told you about one pickup shot we had to do.

Filmmaker: Was that in the park with Cindy Williams?

Murch: No, it was to clarify the fact that tapes had been stolen from the lab. We had to shoot an over-the-shoulder shot of Gene Hackman finding empty tape boxes.

Francis [Ford Coppola] arranged with a friend who was shooting at Paramount to use a corner of his set. He said, “We’ll build a little set and then we want to borrow one of your B cameras and we’ll just be 10 minutes.”

When we wound up doing it, we didn’t have Gene Hackman. It was Gene Hackman’s brother, who had a nice Hackman-like shoulder. I think we shot two or three takes. It was very simple to do, but if we’d kept the camera running and panned over, the camera would’ve landed on Roman Polanski and Jack Nicholson. The Conversation could have been knitted to Chinatown in that single shot.