Back to selection

Back to selection

Five Highlights from the 2023 New Directors/New Films Festival

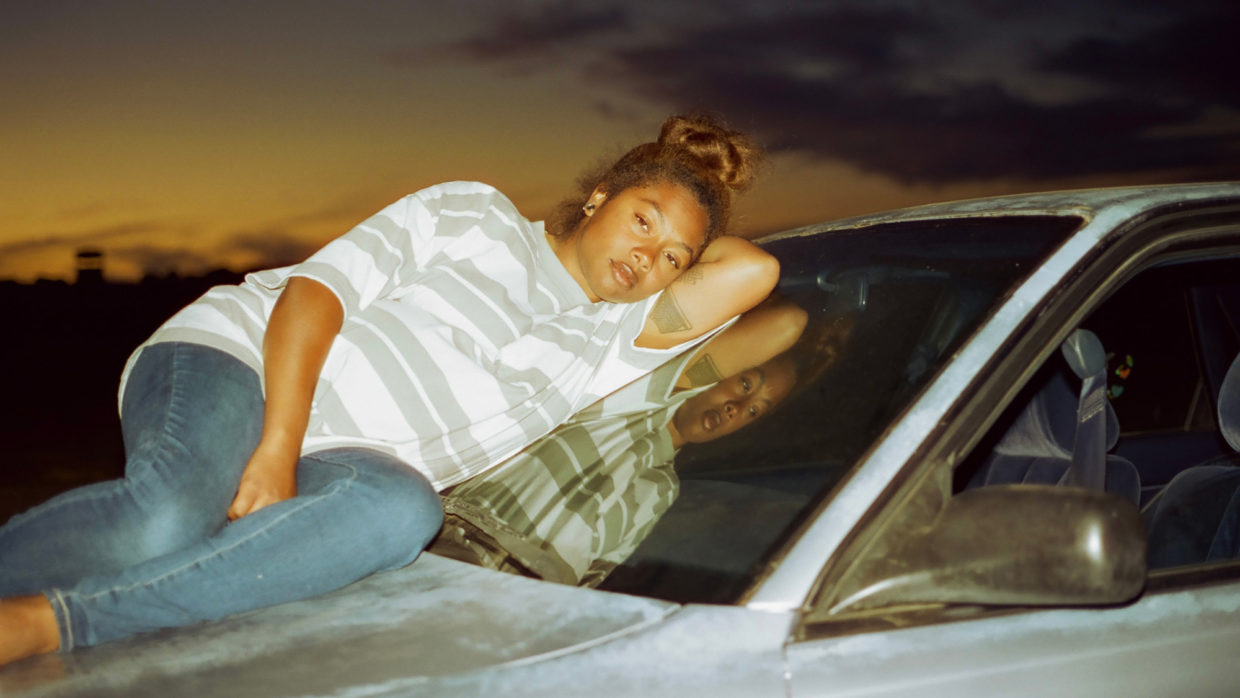

Tia Nomore in Earth Mama

Tia Nomore in Earth Mama New Directors/New Films, the annual showcase of work by emerging directors co-presented by the Museum of Modern Art and Film at Lincoln Center, began this week in New York City and runs through April 9. The 2023 slate features 27 features and 11 shorts, most of them culled from top-tier festivals such as Berlin, Cannes, Locarno, and Rotterdam. As always, ND/NF’s offerings are global in scope, with over 30 countries represented, and the programmers remain admirably committed to arthouse aesthetics: conventional genre films and commercially minded crowd-pleasers are thin on the ground here. This is a festival for audiences willing to let directors try things out. You won’t get a masterpiece every time you buy a ticket — but you will be rewarded with films that are almost always interesting and worthwhile experiments, and on occasion, you’ll see something truly remarkable. Below are five recommendations from this year’s feature selections.

Savanah Leaf’s Earth Mama, the opening night film, arrives by way of Sundance, where it played out of competition. Gia (Oakland rapper Tia Nomore, in her acting debut) is a young Black mother of two, with a third arriving soon. Her son and daughter have been placed in court-supervised foster care. Gia will do whatever it takes to get them back, but economic pressures, bureaucratic indifference, and her own demons block her way. When her social worker introduces her to a kind middle-class family looking to adopt, Gia faces the awful realization that giving up her yet-to-be-born baby might be the only way to secure that child a happy life. Earth Mama is earnest social realism of a kind that may seem familiar on the surface, but Leaf brings to it surprising textures and colors — first and foremost, Jody Lee Lipes’ breathtaking 16mm cinematography, which moves seamlessly from neorealist docudrama to poetic abstraction and dreamlike subjectivity. Leaf maps out the external circumstances that define Gia’s day-to-day existence, while also taking us inside her fears, frustrations and longings, aided immensely by Nomore’s emotionally transparent, deeply affecting performance.

Remembering Every Night, the second feature from the Japanese writer/director Yui Kiyohara, also puts a distinctive personal footprint on well-trod terrain. Over the course of a single day and evening, three women — a recently unemployed kimono dresser in her 40s, a gas-meter inspector in her 30s, and a college student in her 20s — go about their business in Tama New Town, a commuter suburb outside of Tokyo. For the most part, the three remain in their own separate worlds, but every so often their stories intersect as they pass by each other in the street — and over time, the viewer teases out deeper, more intuitive thematic connections between them, largely having to do with memory and the weight of the past.

This kind of linked-chain narrative structure is hardly novel, nor is the wide-frame, long-take visual style Kiyohara employs. Nevertheless, her film moves to its own particular beat. It’s mellow in tempo and mild in affect, uninterested in plot machinations but unerringly alert to small moments (I can’t remember the last time a movie made me so aware of the silent pauses in conversations), alive to fleeting feelings of both melancholy and joy. If you surrender to its gentle, uncoercive rhythms you might find yourself happily seduced by its patient exploration of the everyday.

From a whisper to a scream: The Iranian film Leila’s Brothers is a loud, bustling, sprawling family melodrama that runs 169 minutes, but moves at such a breathless pace that it feels an hour shorter. The titular Leila is played by Taraneh Alidoosti, most familiar to U.S. audiences from her work with Asghar Farhadi. (A few months ago, Alidoosti was arrested for speaking out against the execution of a political prisoner but was released following an international outcry.) Her full-blooded performance drives the story. Leila is the only daughter in the family, and the only real grown-up; her four brothers are all man-children, and their father a doddering, selfish tyrant. She comes up with a plan that will lift them out of destitution, but the father threatens to ruin everything by chasing his vain dream of winning the respect of their wealthier relatives.

The writer/director, Saeed Roustaee, has crafted a multi-generational epic that will bring to mind Visconti’s Rocco and His Brothers and Coppola’s Godfather films, as well as Roustaee’s famous compatriot Farhadi — and not only due to Alidoosti’s welcome presence. As in Farhadi’s work, vividly drawn characters enmeshed in a web of precisely observed social relationships, and an unflashy, uninflected filmmaking style, keep the spring-loaded plot twists of the screenplay grounded in naturalism. Some viewers may think Roustaee pushes those plot twists too far, especially as the surprise revelations and sudden reversals pile up toward the end, but shamelessness in the pursuit of entertaining an audience strikes me as the most forgivable of sins for a storyteller. And there’s a seething anger that gives the movie real bite — Leila’s anger, but it feels like Roustaee’s too — at the injustices, and the endless indignities, of both poverty and patriarchy.

Lila Avilés’ Tótem is also a family drama, but unlike the expansive, operatic scale of Leila’s Brothers, this Mexican film is a chamber piece, intimate and inward-looking. A young man named Tona, ill with cancer, has returned to his childhood home, where his extended family and friends gather to throw him a birthday party. Much of the story is seen through the eyes of Tona’s daughter Sol (Naíma Sentíes). As the party draws near and the house fills with guests, the adults try to tiptoe around Sol, but she knows her father is very sick and fears the worst. I haven’t seen Avilés’ acclaimed first feature The Chambermaid, but in Tótem she displays a quietly masterful command of the medium. The connections between characters are so finely drawn, the actors’ behavior so unshowy, that as the handheld camera gracefully drifts around and between them, it feels as if we’re dropping in on a fully inhabited world. Haunted by death, suffused with love, Tótem lingers in the mind long after it ends.

The Italian director Giacomo Abbruzzese makes his feature debut with Disco Boy, a war movie of startling force and originality. It traces the lives of two young men — Aleksei (Franz Rogowski), a Belarusian who illegally emigrates to the E.U., where he joins the French Foreign Legion, and Jomo (Morr Ndiaye), a Nigerian who helps lead an armed guerilla group fighting the exploitation of the Niger Delta by Western oil companies. When Jomo’s organization takes some French oilmen hostage, Aleksei’s Legionnaire outfit is deployed to Nigeria to rescue them. Jomo battles for his tribe, his village, his homeland; Aleksei, for a country he hardly knows — his commanding officer tells him that if he lasts a few years with the Legion, one day he “will be lucky enough to be French.”

Disco Boy tackles large subjects — migration, the legacy of colonialism, the complexities of national identity, the depredations of capitalism — but above all, the film is a powerfully visceral experience. The great cinematographer Hélène Louvart brings a boldly colored, hallucinatory intensity to depictions of extreme physical states, from the Legionnaires’ punishing military training to the murderous sensuality of hand-to-hand combat to the abandon of sweaty bodies in a packed rave. (The title refers to Jomo’s daydream of the life he might have led if he’d been born to different circumstances: “I’d be a dancer in a nightclub — a disco boy!”) Abbruzzese is evidently not lacking in ambition or audacity; look no further for proof of the latter than the way Disco Boy blatantly invites comparison to Claire Denis’ widely beloved Beau Travail — another movie about the French Foreign Legion that features homoerotic undercurrents and concludes with an EDM dance number. Denis’ mysterious, elliptical masterpiece sets an impossibly high standard, but Disco Boy has a singular power all its own.