Back to selection

Back to selection

Warhol v. Goldsmith: a Narrow Decision Preserves Fair Use As We Know It for Filmmakers

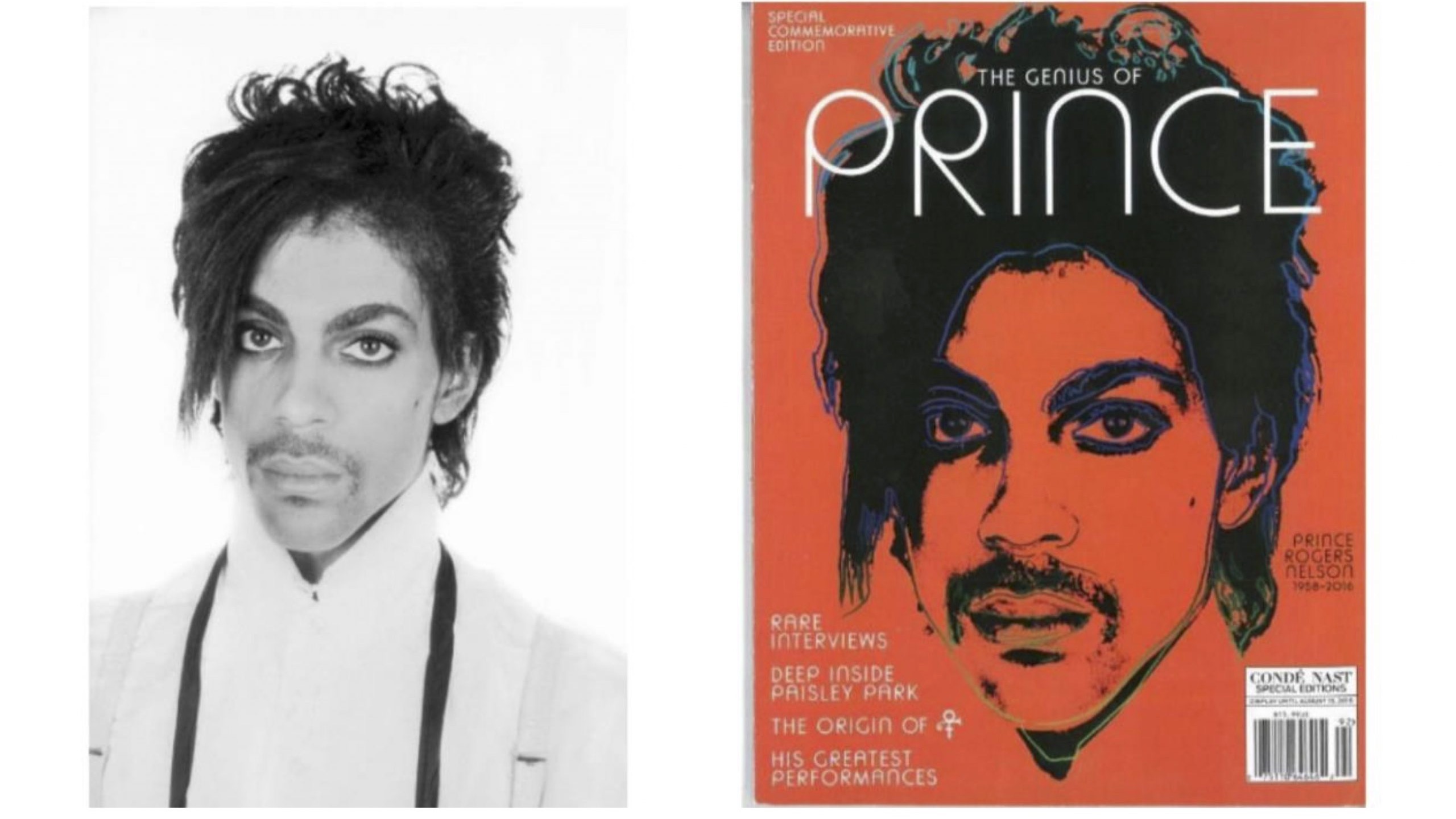

Lynn Goldsmith's 1981 portrait of Prince and Andy Warhol's silkscreen on a 2016 Condé Nast cover. (U.S. Supreme Court)

Lynn Goldsmith's 1981 portrait of Prince and Andy Warhol's silkscreen on a 2016 Condé Nast cover. (U.S. Supreme Court) Fair use, a crucial right.

Since 2005, when documentary filmmakers created their Documentary Filmmakers Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use, fair use has become settled industry practice. Fair use is what lets people quote from their culture for free, in the right circumstances. Ring tone in the scene? Paintings in the background? Want to use news clips to highlight the importance of events in the film or a stanza of a song you’re talking about? Check first to see if fair use applies; it very well might. Insurers cover fair uses, too, because they know the risk is low.

Fair use has long powered all kinds of art. So artists of all kinds were alarmed when the Supreme Court took a fair-use case involving one of Andy Warhol’s iconic celebrity screen prints. This Court has not shied away from diminishing or eliminating established rights.

But perhaps because copyright doesn’t have a partisan divide (both the majority and the dissent were written by justices in the liberal minority, joined by colleagues on the right) it decided this case narrowly, without changing the fundamental shape of the law. As a result, the opinion preserves the fair use rights of filmmakers–and others–who are employing fair use in the routine and common ways important to their work.

The facts matter.

It’s worth looking at the facts that put the case in motion. Even though this case involved Andy Warhol—an artist who based his work on fair uses of popular culture—it’s actually about a particular set of business transactions taking place in a highly structured market.

When Prince was an up-and-coming musician in the early 1980s, Vanity Fair licensed photographer Lynne Goldsmith’s black-and-white portrait of him for one-time use as an “artist’s reference” from which Andy Warhol made an illustration for the magazine. Around the same time, but outside the license agreement, Warhol made 15 more works from the same photograph. After Prince’s death, Condé Nast negotiated with Warhol’s estate to use one of the other works for a commemorative cover. No one paid Goldsmith this time. She was not happy about that.

Should she have been paid this time around? Or could the Andy Warhol Foundation claim fair use? It’s been a long and winding legal road since 2016, but the upshot is this:

The Supreme Court says the Foundation should have paid Goldsmith again.

Why?

Transformativeness.

Licensing the Warhol Prince image to Condé Nast wasn’t fair use mainly because it wasn’t “transformative,” and transformativeness—the difference between the purpose of the original work and the purpose of the new use—is critical to deciding fair use. The purpose of the original Goldsmith photograph and of the version that the Warhol Foundation licensed to Condé Nast in 2016 were nearly identical: both served as portrait illustrations of Prince for magazine features about Prince. That made the Warhol version a “competing substitute” for the Goldsmith version, always a blinking red light on the fair use dashboard.

A key issue in the case was whether adding “new meaning” to an existing work is enough on its own to make a work transformative. The Warhol Foundation argued that its Prince portrait added commentary on the dehumanizing quality of celebrity, a meaning that wasn’t present in the Goldsmith photograph. The Court didn’t think this was enough of an argument for fair use here, however. That’s because the ultimate purpose of the use—to illustrate a magazine about Prince—was still the same. The court said new meaning can be helpful when it shows your use serves a new purpose, but if your purpose is the same, new meaning isn’t enough.

For example, a play adapted from a novel often adds meaning in the process of recasting the book for a new medium. Dialogue may change; characters may be added or combined; choices of directors, performers, set designers, and costume designers can give the author’s vision new dimensions, but the same story still is being told for the same narrative purpose. Such an adaptation is not a fair use; it’s simply a “derivative work”–based on something preexisting but not different enough to be considered transformative.

So when could the Warhol version of Prince have qualified as transformative fair use? According to the Court, examples could include its recontextualized display in a museum exhibit, or its use as an illustration in a book about Warhol (or perhaps, by extension, a documentary about late 20th century celebrity)–instead of a magazine piece about Prince.

Since avoiding unfair commercial competition is a major concern for fair use–and copyright in general–the judgment noted that Warhol’s licensing activity here was commercial. Commercialism is a problem for fair use when there’s not a new purpose. As the Court observed, “If an original work and a secondary use share the same or highly similar purposes, and the secondary use is of a commercial nature, the first factor is likely to weigh against fair use, absent some other justification for copying.”

And yes, most filmmakers do commercial work. But that shouldn’t change their thinking about fair use substantially, post-Warhol. Where fair use flourishes in filmmaking–i.e., where transformativeness is present–this consideration should have little weight. After all, a huge amount of daily employment of fair use is commercial and also uncontroversial. Think about every late-night TV show that makes fun of the day’s news or pop culture, or every search engine that serves up links to appropriate content. Those providers are commercial, for sure, but because their services fulfill fundamentally different purposes, they don’t replace the original in the market.

Filmmakers’ core argument for employing fair use in various common, recurring situations—that the purpose of the use in these circumstances is new—will continue to be strong after Warhol. Filmmakers should continue to ask their two big questions, when thinking about unlicensed reuse: Am I doing something substantially different with this than its normal purpose? (Am I including this snippet of a popular song because I think my audience will like how it sounds, or because it illustrates the phenomenon being described by a music critic?) If my purpose is new, am I taking the amount appropriate to accomplish it? (Am I taking an amount of that song that is pertinent to the critique or am I lingering just because it sounds so good?) When your use satisfies these two criteria, you should be on solid, fair-use ground.

Super-specific.

The Supreme Court decision (written by Justice Sonia Sotomayor) also makes a great effort to note how narrow and specific it is. The ruling is only about the “specific use alleged to be infringing,” and “expresses no opinion as to the creation, display, or sale of [Warhol’s] original Prince Series works.” Justice Sotomayor and the majority of the Court say they respect the artistic value of appropriation art, and of all artists who must borrow from others as part of their process. They go out of their way to note that the decision does not mean that “derivative works borrowing heavily from an original cannot be fair uses.” Indeed, they appropriate (and reproduce) Warhol’s use of Campbell’s Soup labels as an example. Those cans faithfully copy the instantly recognizable label, but they serve entirely different commercial purposes. Andy Warhol was not selling soup.

What the Warhol opinion does make clear is that when you borrow from an artist, and then compete directly with that artist in the the specific, structured, commercial licensing market where they operate, you will have a harder time making a fair use argument than when your use serves a commercial purpose and appeals to a new new audience of consumers.

Context is crucial.

This decision does remind us, helpfully, that fair use is always decided in a specific context. It was the highly specific context of the magazine publisher’s decision to reuse specific content from the Goldsmith Prince photo without relicensing it that led to the Court’s decision.

That’s important for filmmakers, because when they consider whether they can employ fair use, they too have to think about context. The answers to those two questions—is my use transformative? Is the amount I’m taking appropriate?—will depend entirely on the context of the use. The same work may be fair to use in one context, but not in another. So the Warhol decision once again reinforces what we already know.

Some contexts are common.

While each use context gets its own analysis, a few key contexts come up again and again for most fair use communities. That’s what documentary filmmakers found out when they created the Documentary Filmmakers Statement of Best Practices in Fair Use: they rely on fair use again and again in four common situations.

One person may be making a film about prison reform and someone else may be making a film about a band’s farewell tour, but they both will find themselves in one of these four common situations: Quoting media you’re talking about, from any media; using material to illustrate something you’re talking about; showing material you caught in passing while documenting some reality; excerpting media to make certain kinds of historical references. The contextual logic of them all makes the thinking you have to do in each category very similar, every time.

Knowing what is uncontroversial, routine and normal in your field makes a huge difference as you try to decide if your claims to fair use are legitimate. That’s what the best practices do, and a good fair use lawyer can help you, too.

In the legal weeds.

If you’re tempted to read the decision itself, plunge in; it’s here. You’ll notice that the court spends its time and effort on the “first factor” of fair use. That’s one of four factors that judges consider when they have to decide on fair use. Those four are: the purpose of the use, the nature of the work used, the amount used, and the market effect of the use. The Court reminds us that these considerations are useful in maintaining balance between the rights of a copyright holder and the rights of new user–to which U.S. copyright has aspired for its 200+ year existence.

But how do judges make sense of those factors? Since 1994, a judicial consensus has gradually evolved that makes transformativeness the key to this analysis. They ask to what extent the use is for a new purpose, comparing the nature of the original to the new use in the process. Then they consider whether the amount used is appropriate to the transformative purpose. Finally, if a work is for a strongly transformative purpose, then it will not threaten the market of the original, so the answer to the fourth factor also will favor the user.

This decision looked only at the first factor, the purpose of the new work, because that’s the only issue on which the Warhol Estate asked for review. The Court puts more emphasis than in recent years on commerciality, but not in a way that should affect the thinking of filmmakers or other artists who conventionally operate in a commercial environment–i.e., almost all creators.

Justice Elena Kagan’s dissent warns that the majority opinion will have a chilling effect. We share Justice Kagan’s view that art and culture are fundamentally cumulative and recombinant, that “nothing comes from nothing,” and that fair use protects creativity. But in the end, we think the Warhol opinion is not about art as we know it, or even this particular art. It’s about commerce. It’s important for filmmakers not to succumb to any chilling effect, as this decision has been carefully designed to be narrow in its impact.

Do filmmakers really need to do an elaborate legal analysis before shooting a film? Not really, although consulting and establishing a relationship with a legal specialist may be a good idea, even early on. If a filmmaker does make fair use of copyrighted material, they’ll will need a lawyer’s letter to get errors and omissions insurance–and a lawyer can do the formal analysis at that point. Definitely, however, you can help yourself and lower your legal costs if you do what the Documentary Filmmakers Statement walks you through—that two-question decision-making, within the context of common situations. Those are the questions that will drive fair use law post-Warhol, just like they did before.

About the authors:

Patricia Aufderheide is University Professor in the School of Communication at American University. Brandon Butler is the Director of Information Policy at the University of Virginia Library. Peter Jaszi is an Emeritus Professor of Law at the Washington College of Law, American University, Washington, D.C. Butler and Jaszi are co-founders of the law firm Jaszi Butler PLLC, a boutique practice that specializes in fair use consultation.