Back to selection

Back to selection

Looking Towards 2043: The Worldbuilding Weekend of Experimental Realities

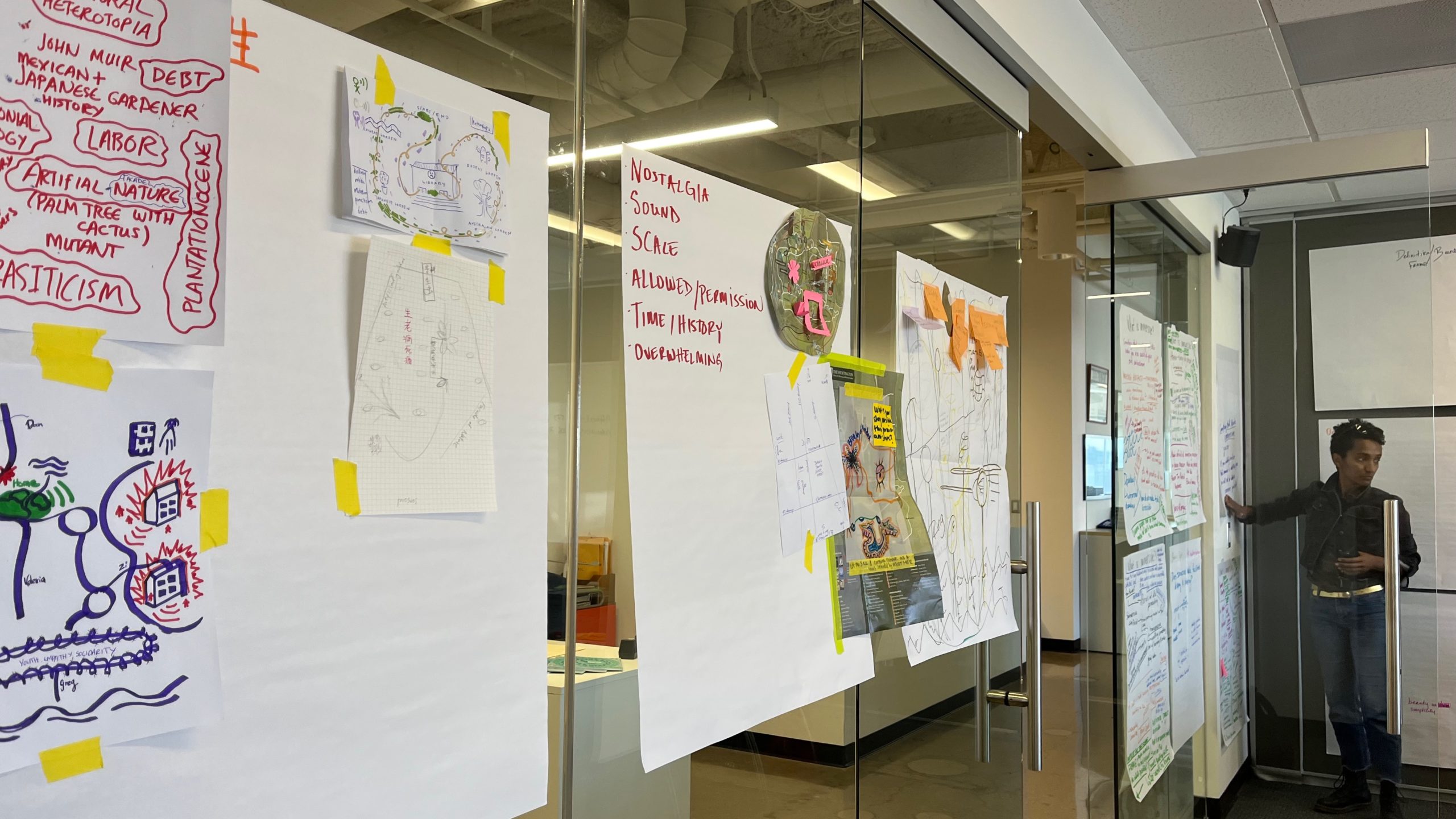

The whiteboards at Experimental Realities

The whiteboards at Experimental Realities In early July, a cohort of over a dozen filmmakers and artists gathered in the International Documentary Association’s sun-drenched conference room. Some had flown in from as far away as the UK and Serbia, others were local to LA. A number—perhaps most of them—weren’t exactly sure what was in store for them at the weekend-long Experimental Realities event. Or even why exactly they were there.

I asked the event organizers how members of the impressive group — who included Greg de Cuir Jr., Alison Nguyen, and Mark Mushiva — were selected. “This is funny because the participants have been asking us this too,” Keisha Knight said with a laugh. Knight and co-organizer Abby Sun both work at IDA, and they reached out to filmmakers they admire and asked friends for recommendations. They scouted for artists excited by experimental and collaborative opportunities, artists who they felt were capable of “negotiating unknown space,” as Knight put it, and thus would be game for this one-of-a-kind convening.

The work of Adrienne Maree Brown, especially her 2017 book Emergent Strategy, served as inspiration for Sun and Knight. To Sun, the book offered an encouraging takeaway for artists and activists in the face of uncertainty: that if you gather a committed group, even if “perhaps you don’t know where you’re going,” the “shifting shape” of the collective will guide the group to ideal outcomes. Emergent ideas can be difficult to put into practice, Knight said, because “there’s a refusal of institutionalization” that goes along with it. That’s why, in assembling the Experimental Realities, Sun and Knight chose to focus on artistic practice and open-ended creative experiences. No one had to pitch a project and work on that project, as they would in traditional film fellowships at labs and incubators. Their own curiosity was all that was expected of the participants.

Practice-based rather than project-based fellowships are more commonly offered in the art world than in film, which is why they reached out to The Warhol Foundation for funding (disclosure: I have also received a grant from the foundation, but I was assigned to cover this event independently). By focusing on filmmaking as a practice, the field of potential participants expanded to include artists who perhaps haven’t made work in years and perhaps are experiencing creative block. It expanded to include “multi-hyphenates” and artists who haven’t worked in film before. And as an experience, Sun and Knight aimed to create a respite from the sense of obligations and responsibilities and deadlines and hustle that plagues 21st century creative life.

So the confusion at the start was a bit inevitable. To realize the collaborative potential of the group and build community, Sun and Knight organized ice-breakers for the first day, many circling back to one of their goals for the event: to imagine new ideas for immersive nonfiction filmmaking.

“What is ‘immersive’?” Knight asked the group at the start of the first session. She scribbled suggestions and word associations on easel-pads as participants discussed what the word meant to them as artists. Some in the group pushed back against conventional ideas about immersive art and even the desires for it. “Why do we have the need for immersive experiences? What is it about the stakes of reality that is so impoverished that we need immersive media—is it really more free?” asked Nguyen. “If anyone has made immersive work, it’s actually really curated and edited in museums and thought-out.”

Later that day, filmmaker Tony Patrick joined via video from London. Acting a sort of gamemaster for worldbuilding exercises, he invited the group to imagine the year 2043. “Think about things you would like to see,” he said. Most of what was suggested, including universal healthcare and funding for the arts, would require progressive policy and political will rather than more advanced or even alien technologies.

Worldbuilding, like any other team-building exercise, can be a little bit corny, and the organizers anticipated some resistance. As Sun explained to me later, “the actual work of worldbuilding is not as important to me as creating the shared experiences.” The group needed a catalyst, something for members of the group to “flow with or against,” she said, including Patrick’s amiable facilitation.

At one point, a participant questioned the value of the exercise, “We need all this now, we need it today. So why talk about 2043?” It was a sentiment that likely others in the group shared. But Patrick answered forthrightly that the apparent triviality of what they were doing should be seen, rather, as a creative luxury. Creating space to imagine, as they were together, was, in Patrick’s words, “a runway” for more radical thinking.

On the final day, the participants — now well-acquainted with each other following several meals together and sightseeing — gathered into three groups. Each group had that Sunday to brainstorm an “impossible” project for the year 2043. And it was here that their collaborative creativity began to flourish. The first group presented an imagined social movement and manifesto “releasing ourself from the pressure of time and timekeeping.” This would involve the destruction of all clocks, even atomic clocks, and anything perpetuating Western narrative structures; further actions would include “instructing projectionists to rearrange film reels so there’s no beginning, middle, or end.” The second group proposed “6D Glasses” which would reveal a “non-victor’s history.” As an individual walked through a space, they would experience a VR-style layer revealing stories of the people that have been displaced for all of time—their labor, their defeats, and their hardships. An impossible project because, as one of the members of the group said, “how can you understand all of history without going mad?” The third group—with perhaps the least possible of all impossible projects—proposed a kinetic sculpture called the “Conscious-nome” that could create spontaneous synchronization like laughter or crying but for creating consciousness in sync.

So what’s next for the Experimental Realities cohort and their impossible projects? Well, that’s also open-ended.