Back to selection

Back to selection

Speculations

by Joanne McNeil

Authoring Your Life Story: Joanne McNeil on Self-Archiving and George Westren

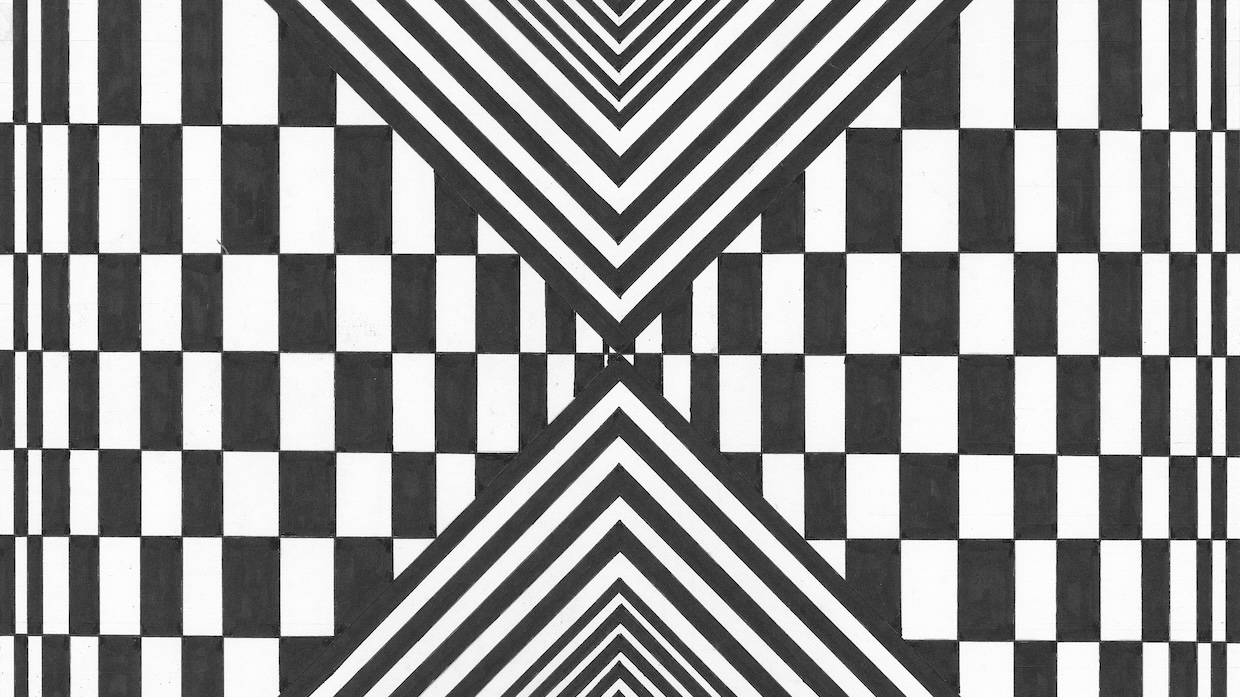

A detail of George Westren's "Diamonds in Stone"

A detail of George Westren's "Diamonds in Stone" For any artist who works with digital files in the twenty-first century (that’s most of us), the work—in addition to making the art—is making sure it sticks around.

To both archive and maintain your own work is a reminder of the gap between current practice and public markers of success. It can feel like an exercise in futility: If this work was really worth it—if someone other than you believed in its value—wouldn’t you have the time and money and institutional support to do it right? A library would offer to acquire your letters, no? Or, perhaps, with awards, grant money or even profits, you could hire a professional? Beyoncé, for instance, has employed digital archivists since 2011. A GQ profile of the artist in 2013 revealed that inside her office there’s a “temperature-controlled digital-storage facility that contains virtually every existing photograph of her, starting with the very first frames taken of Destiny’s Child, the ’90s girl group she once fronted; every interview she’s ever done; every video of every show she’s ever performed; every diary entry she’s ever recorded while looking into the unblinking eye of her laptop.”

I have one good personal archiving habit—clearly marked file names—that I coast on, along with an external hard drive, Time Machine, the Internet Archive and crossed fingers. Writing for print also helps. Often, when I tell people I write for Filmmaker, I hear in response, “Oh, I was just at someone’s house and they had a tall stack of Filmmaker magazines.” (If they are not, themselves, the owner of a tall stack of issues.)

I’ve been thinking about archiving after recently talking with my friend, the artist Alan Warburton (featured in this column in the summer 2019 issue). Last year, Alan discovered the artwork of his longtime neighbor George Westren was set to be disposed of. Westren had died alone in his apartment the previous year, and a clearance company had finally come to remove his things. The two were longtime neighbors but never really knew each other. Alan didn’t even know his neighbor was an artist.

“I wasn’t ostensibly connected to this person, but [the fate of his work] really does stir up all of those feelings about impermanence or permanence,” Alan said. He tweeted out images of Westren’s art that he salvaged, and they went viral, resulting in a flurry of legacy media attention. Alan thinks the story resonated because of its timing. Through COVID, many of us were dealing with complex feelings of grief, with “loads of people having lost family and having to deal with houses and estates and rooms full of this and that.”

I saw Alan’s posts in 2022 and was terribly moved by the images of Westren’s work and the tweet-size story of how it all had nearly ended up in a landfill. What I didn’t know, until we talked recently, was that Alan had felt “primed” for such a rescue mission, since he had been streamlining his own personal archive that summer. Having given up his studio, and without the space in his apartment to hold on to all his work, he methodically went through everything, even “boxes that my mom had given me of artwork going back to when I was five.”

As Alan explained via Zoom from his home in London, it sometimes happens that he will give a friend a hand-drawn birthday card, and they will say things like, “I’m going to keep this because this’ll be worth something.” But will they—and does it matter? “That expectation weighs heavy on all artists,” he said. “We’re all sort of fighting through this process of trying to be the artist that everyone expects us to be, who has the legacy and the archive and whose signature is worth something.” He streamlined the box of his childhood artwork from thousands of images down to less than a hundred. Even before discovering Westren’s work, he was thinking, “What story is it that I want to tell about my own life? I don’t want to burden anybody if I die for whatever reason. I don’t want someone to have to go through six boxes of my stuff. I want them to know what’s important.”

I asked Alan whether it mattered that George Westren’s work was good. (It’s visually stunning Op Art, Bridget Riley–style—the kind of art that grabs a person’s attention even on a noisy platform like Twitter.) But it wasn’t the obvious talent that necessarily struck Alan when he discovered Westren’s portfolio. “It was obvious how much time had gone into it,” he said. “[The time involved] was its own kind of currency.”

The months following were a whirlwind of attention for Alan. He helped set up a print sales site for Westren and an exhibition of the late artist’s work. It was bizarre for the living artist to experience his 15 minutes of fame based on art by someone else. Meanwhile, he also found himself as the “node” that “joins together [Westren’s] family and all of his friends and the fellow artists and the places that he went to practice art or to meet friends. I’m suddenly occupying this space where George once was.”

I asked Alan how this experience changed how he thinks of art or what art is to him. I know I’m going to remember his response. “I never wanted to be famous,” Alan said. “I don’t want to be rich, really. But I would like to be able to subsist at a level—and I suppose I sort of know that with art, you’re never going to get that. And even if you do get it, it’s out of your control. Somebody comes along and discovers you, or hard work doesn’t really pay off. It’s sad. Even in death, it can be lost. So, just enjoy your fucking life. Just do whatever the fuck you want. That, I guess, was the message. But it also made me realize how capable I was and how if I throw myself into a situation, I’ll be OK.”

Westren’s family has now assumed the custodial work, but Alan still encounters moments where he feels responsibility for Westren’s legacy. Those tweets that kicked things off—is it OK if he deletes them? If he deletes his Twitter (or “X,” rather, another fracture in cultural memory) account, how does that impact the memories of others?

I have for the past year been dragging my feet to sort through work, a process similar to Alan’s before he was thrown into rescuing Westren’s archive. It’s a daunting task, freighted with baggage like my ego, feelings of uselessness and worries about mortality. But from this conversation, I now see the labor of archives in a new light. It is, as Alan said, not simply the protection of physical objects, or data, but a way to tell your own story.