Back to selection

Back to selection

Girlblogging: The Love Witch

The Love Witch

The Love Witch This post is part of a series, Girlblogging. Read the introduction here.

Maybe you have seen this image: five outlines of a head (turned sideways in profile), each holding (in its mind’s eye) one of four images of apples stamped (from left to right) in decreasing order of detail, except for the last head, which is empty. This is an image of images, an image about how imagination works.

At its most basic level, imagination is image visualization. When you think of an apple, what do you see?

In The Love Witch (2016), witchcraft looks a lot like imagination—energy concentrated and directed; belief doubled; the image visualized, hyper-extended into reality—as it bleeds into manifestation: the ability to visualize an image so clearly that it becomes true, that you come to live in it. You are seeing things transitively, seeing them into existence rather than seeing them as they are. From the apples in your eyes, the order is reversed—from fantasy to form, image to reality.

After a bad heartbreak, Elaine Parks (Samantha Robinson) drives herself away to a new town (Humboldt County, California) and a new life as the Love Witch (a title that appears to be self-appointed; she names herself over and over, manifesting herself in a speech act, an incantation).

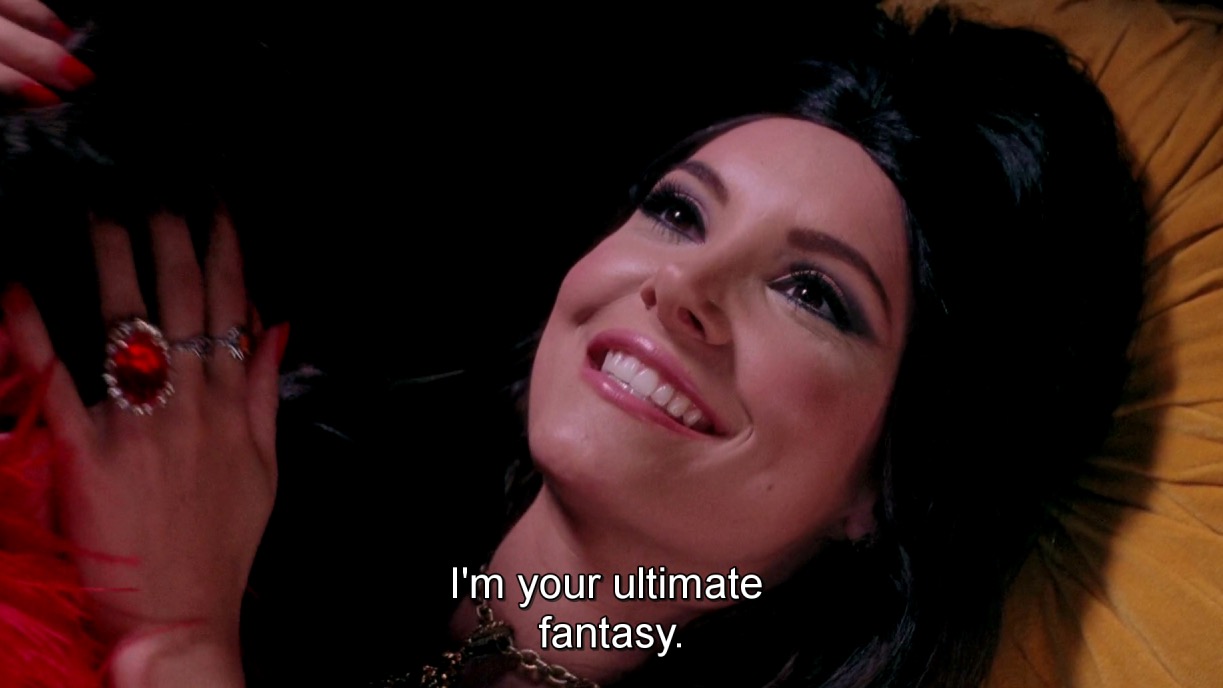

I’m the Love Witch. I’m your ultimate fantasy. She looks the part. She’s a dream girl; in the stylized throes of sexploitative passion, she’s made herself up to be; her skin is plush and taut and poreless, dusted with the pink bloom of love and satin-finished; her belief wells up in her darkened eyes, spilling over to shade the world around her. Like the film’s stylized approximations of psychedelia, Morricone, and Technicolor, plus Robinson’s waxen haunted-doll affect—she moves through emotions in postures, perfect images; like a model more so than an actress—gelled together into a tonal filter, life is the way Elaine sees it.

Now my life is sweet like cinnamon, sings Lana Del Rey, and so it is. Lana’s not on the soundtrack, but she looks like she should be; under one in a string of doomed lovers (this time, her best friend’s husband) with her hair pushed into a vague bouffant, Elaine wears all the same images—dark brows and long lashes, winged liner, cleft-tip ski-slope nose—in the same blurred outline of the retrograde feminine: the same belief in romance, in belief itself.

Girls are supposed to believe in things: astrology, health benefits, fads, ghosts, fairytales, mythologies, beauty, luck, love. Suitors speak in promises, like artists and advertisers—This [IMAGE] will build you a world!—that’s how fashion shows work, and lyrics, vibes and impressions and moodboards: these things share things in common because we believe they do (shades of blue).

A girl can believe she is a swan, a siren, a slant of light, an album cover, a dream, a flower. It works if you work it—if you buy in, if you believe hard enough. The Young-Girl wants to believe. She lives to believe, to manifest herself as perfect: the perfect consumer, the perfect lover, the perfect image, your ultimate fantasy.

At first, belief is a little furry thing—soft, cute, harmless. But sometimes a girl believes too hard. What is for you will find you. A delulu girl is a forever optimist.

Delulu means delusion: truncated, bastardized, the original word simultaneously stretched in the middle and collapsed, diminished. To be delusional is to have a mental condition. To be delulu is to be in love. Though really, where’s the line? It’s all made up—not in the contemporary way, where your skin looks like skin, but in the plastic beauty-pageant way—the paste eyeshadow, the 60s pastiche, the acid-trip overlay.

Elaine recolors her world; so too does the girlblogger. The film is this pink, in a few scenes set in a blush-hued tearoom, but it is not this pink: the images served up here are tonally exaggerated, retroactively edited. That’s what you do when you’re delulu. You pull out a thread—a small shared interest or a gesture or a tone of voice—and with it, shade everything.

In this transcript of Elaine’s confession, the text is colorful, whimsical; in a pastel rainbow gradation, it obscures the truth while revealing it. Is it still a confession if she believes she’s done nothing wrong? What if—by the strength of her belief—she gets away with it?

Men have Patrick Bateman, I have her. Though he’s trapped there, Bateman makes it back to reality; Elaine’s life, on the other hand, runs up against the image in her mind.

No one really wants a fantasy. Maybe the perfect image of a person wants a perfect image. But a human being doesn’t want an idea—it wants another human being.

I’m the love witch! I’m your ultimate fantasy! The apple of your eye.

These are the wrong words with the wrong scene, but it’s still true, isn’t it? It’s true because it looks true; seeing is believing, and it’s true if you believe it. You believed it before, and now, what’s changed? I’m on my own again, still wearing your blood, still holding the knife—

Don’t worry about it! It’s all in your head.