Back to selection

Back to selection

PRODUCING ONE HUNDRED MORNINGS, PART ONE

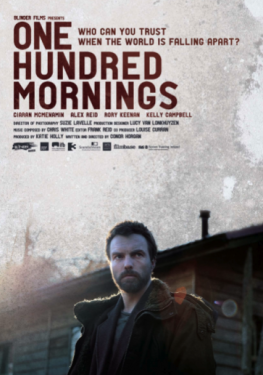

I was one of the judges for this year’s Wookbook Project Discovery and Distribution Award, which grants one lucky film a week-long theatrical run in L.A. with social media, street team and PR support. That run begins this week, September 16, at the Downtown Independent Theater, and the film is Connor Horgan’s character-based post-apocalyptic drama, One Hundred Mornings. All this week we’ll have blog posts from producer Katie Holly and Horgan here at Filmmakermagazine.com. Below is Holly’s first post on the producing of the film. — Scott Macaulay

I was one of the judges for this year’s Wookbook Project Discovery and Distribution Award, which grants one lucky film a week-long theatrical run in L.A. with social media, street team and PR support. That run begins this week, September 16, at the Downtown Independent Theater, and the film is Connor Horgan’s character-based post-apocalyptic drama, One Hundred Mornings. All this week we’ll have blog posts from producer Katie Holly and Horgan here at Filmmakermagazine.com. Below is Holly’s first post on the producing of the film. — Scott Macaulay

One Hundred Mornings was made for a tenth of the budget that the first feature I worked on eight years ago was produced for. Back then a million euros was considered ‘low budget’ but now there is a new wave of indie filmmaking in Ireland that is embracing both the possibilities of new technologies and of new models of production. The Irish Film Board’s micro-budget scheme which fully funds features up to a maximum budget of EUR 100,000 (approximately $130,000) has produced some of the country’s most original films from the past few years, including Ken Wardrop’s His and Hers, which was a Sundance winner and has recently passed the 300,000 EUR mark at the domestic box office — a success by any standards, not least for a documentary.

One Hundred Mornings was made as part of a scheme called Catalyst, which sought to give new filmmakers — writers, directors and producers — an opportunity to make their first feature. The scheme kicked off with a series of weekend workshops, attended by over 150 filmmakers, where panelists — ranging from established producers like Christine Vachon, to first ADs, production managers and distributors — sought to impart their advice on working on low-budget productions. Notwithstanding their wisdom the experience alone of being in a room with so many aspiring filmmakers was invigorating. We screened, ate, talked, drank movies together for several days; indeed my second feature film Sensation, which has just premiered in Toronto, came out of my meeting the writer/director Tom Hall on those workshops, as did many other films.

Making the film as part of a scheme certainly had it’s benefits — for one thing an agreement was made with the Unions so that a flat daily rate applied across the board for cast and crew (along with a shared revenue pool for each group). The chosen films were fully funded and there was a mentorship aspect to the award so that all our key crew (most of whom were upgrading to Head of Department) could avail of practical support from experts in their field throughout the process. Furthermore the fact that writer/director Conor conceived of the story entirely with the scheme in mind undoubtedly helped in that as he was writing he was thinking of the limitations our budget would impose in terms of scale of the story and length of shoot. A world without electricity. Two couples. One lakeside cabin. An apocalyptic film that focuses more on a set of characters’ response to their changed circumstances rather than on the event itself. So, a small cast, one key location, limited lighting and set design and a stylistic emphasis on relatively long scenes and single shots.

Of course when we broke all this down we realized that we still needed an armourer, animal handlers, stuntmasters, special effects supervisors, a week of split days and nightshoots, and to somehow create the effect of moonlight on a big exterior location as there’s no electricity in the world of our film. Not so simple as it first appeared…

Every film presents its particular challenges and we were extremely lucky to have such a committed team and such strong goodwill for the scheme in the wider industry. It allowed us to achieve all of what we scripted without too much compromise. Twenty days to shoot a feature isn’t a lot, particularly with so many first timers, among them producer, director and DOP. Again the planning and approach was crucial — had we attempted lots of coverage on each scene we never would have made our days and our schedule. We did get a little behind but our last day’s shooting was exhilarating and so memorable — I have never before and don’t think I will ever again get through so many slates in one day, and we got it done…

Assembling as we shot was immensely beneficial as it helped us assess what scenes we could drop, merge, or re-write, thus getting around the need to do potentially expensive pick-ups down the line.

It was an amazing experience making One Hundred Mornings and I learned so much that I will take with me to future productions. “Nothing is impossible” would be a good summation. What I hadn’t envisaged at the outset was just how long the whole journey of the film — from prep to actually getting the film to an audience — would take. In fact, it’s a process that is still ongoing. One thing that was sorely lacking, and this is surely common across a lot of independent films, is the availability of sufficient marketing and p&a funding, which is so crucial in terms of positioning the film and getting it seen. No matter how careful you are on such a tight budget it’s ferociously difficult to preserve funds for the future life of the film. I look forward to picking up the conversation about that particular journey, which started with our international premiere at Slamdance at the start of this year, in my next blog which will follow soon in the run up to our LA run at the Downtown Independent starting Thursday, September 16th. Until then you can join the conversation and follow the film on our website and on twitter @100mornings. — Katie Holly