Back to selection

Back to selection

“It’s Not about the Days of the Dead, It’s About the Dead in my Family”: Lourdes Portillo on The Devil Never Sleeps

The Devil Never Sleeps

The Devil Never Sleeps The following interview with filmmaker Lourdes Portillo by Bérénice Reynaud was originally published in our Spring, 1995 print issue, and it is being reposted today alongside the sad news that Portillo has passed away at the age of 80. — Editor

“We’ve been told forever that films should be objective, but we knew that was not going to get us anywhere, because if you don’t have a point of view, you don’t have anything,” comments Lourdes Portillo on her approach to Las Madres: The Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, the 1986 film she co-directed with Susana Munoz. Nearly ten years later, the San Francisco-based filmmaker still holds the same opinion in regard to her latest work, The Devil Never Sleeps.

Portillo’s new film is a fascinating, highly personal documentary in which she strives to unravel the events leading to the death of Oscar, her favorite uncle in Mexico. Was it suicide? Was it murder? And if murder, why? The film delves into family romance and elliptically deals with the unspoken presence of witchcraft and the “mystery” of Oscar’s sexuality. Portillo chose to combine interviews, reenactments, and Mexican melodramas to structure the film after Oscar’s second wife, Ofelia, refused to grant an interview or to release documents about her deceased husband.

Born in Mexico, Portillo emigrated with her family at the age of 13 to the United States. An avid consumer of popular cinema, “radio-novellas,” and comic books, she fell in love with cinema because of “its ability to create a new reality within reality.” In the ’70s, she attended the San Francisco Art Institute and co-directed a feature about the Nicaraguan insurrection, After the Earthquake (1978). In addition to Las Madres, her film and video works include La Ofrenda: The Days of the Dead (1989), Vida (1989), Columbus on Trial (1992), Mirrors of the Heart (1993), and Sor Juana: Phoenix of the Americas (1993).

The Devil Never Sleeps was funded by the Independent Television Service (ITVS) and premiered at the Toronto Film Festival before travelling to the Independent Feature Film Market, Sundance, and New Directors/New Films.

Filmmaker: The Devil Never Sleeps is your first feature film and it is also the first time that you appear physically in one of your works. How did you decide to take such steps in your career?

Portillo: I decided to make the film because I was upset. After my uncle’s death, I became obsessed with my family narrative. So a friend said, “Why don’t you make a movie about it?” In La Ofrenda, my voice is in the film, but very timidly, and I thought that I needed to reassert myself more forcefully. The Devil Never Sleeps is also such a personal story. It’s not about the Days of the Dead, it’s about the dead in my family. So it made sense that I should be in the film. Then I realized that I wasn’t going to get an interview with Ofelia, my uncle’s widow. I had her as a voice [Portillo secretly recorded a conversation between the two of them and used it in the film], but visually, what was going to [replace her]? So I decided that it would be myself.

Filmmaker: Some sequences of the film are almost narrative. For example, you have a documentary shot of men working in the harbor, with the ships anchored, accompanied by some very emotional Mexican songs. Then we start hearing the voice of your cousin Catalina, and we cut to Catalina speaking from another space. By juxtaposing these two shots, you create a fictional situation.

Portillo: I decided early that the film would be structured as a dramatic work. Every time something wouldn’t work as documentary, we worked it out in a dramatic way.

Filmmaker: So whenever you had gaps in your information, you resorted to fiction. And every dramatic situation means that you didn’t really know what else to do, in terms of digging for the truth?

Portillo: There were moments when you couldn’t dig. There are cultural boundaries that you cannot cross, because if you do, you’ll lose everything. I talked to someone who wanted my film to be more pointed, who would have been really happy if I had gotten my cameraman, gone to Ofelia’s house, knocked at the door, and just pushed my way in… and had the chow chow bite us! But I couldn’t do that – I would have lost every conversation with her.

Filmmaker: Did you shoot in several stages?

Portillo: Yes, I first went to Mexico with a Hi-8 camera, and I shot pre-interviews. Then I went back with the cinematographer and we shot in 16mm. Later, when I discovered that certain things were missing, I sent one of our assistants to do some reshoots in Hi-8 and to collect photographs. So there were three different trips. When I was shooting in Hi-8, people would get very comfortable and would say all sorts of things to me. When we came with the 16mm camera, they clammed up and they didn’t repeat what they had told me earlier. So I had to reinvent the film. I had to find a way to match the 16mm footage with this very bad quality Hi-8.

Filmmaker: Is this why you inserted the shot of those people talking within the frame of your sunglasses?

Portillo: Yes, exactly. I staged this whole thing to “aestheticize” the bad quality of Hi-8 and give it a different tone.

Filmmaker: I know you were being careful, but do you think that you alienated some members of your family by making this film?

Portillo: I will only know when they see the film. They keep calling me, and they’re dying to see it. There might be some moments in which they’ll disagree with me, some things they will say they didn’t say. But I’ve known them all my life as very generous, very warm people. I don’t think they will resent me.

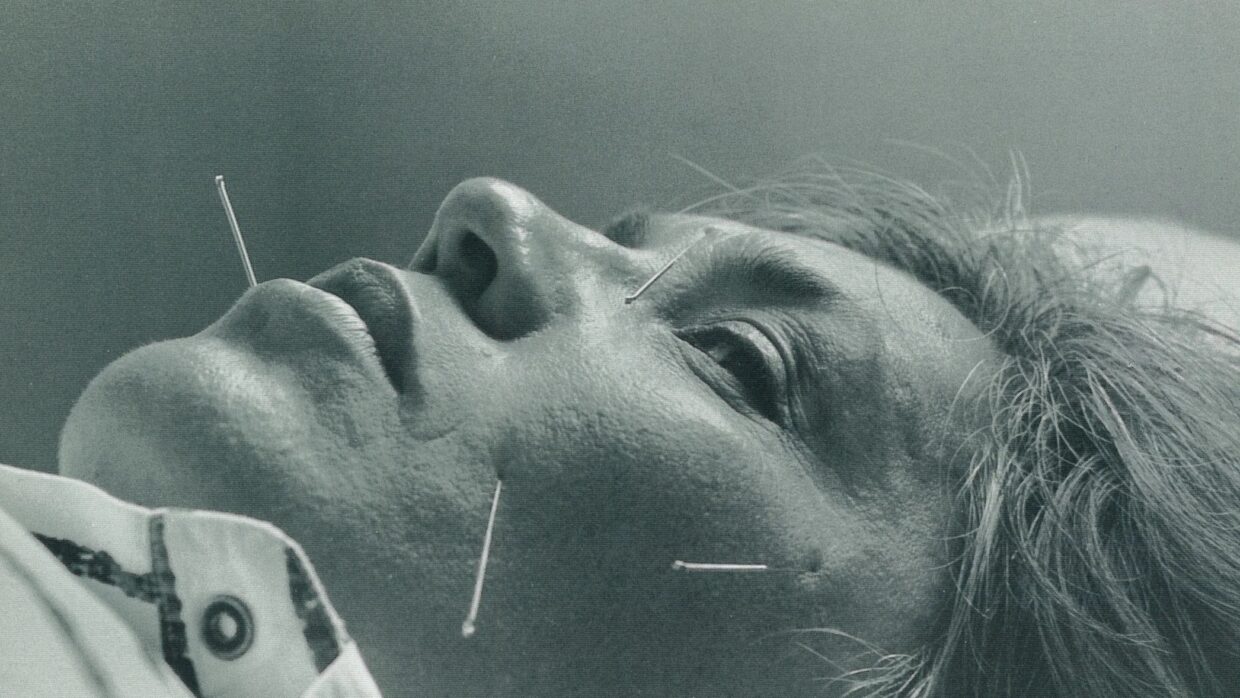

Filmmaker: The shot that has somehow become the symbol of your film is the close-up in which acupuncture needles are inserted in your face. This is only partially explained by the fact that at some point your uncle had studied acupuncture. What are your reasons for displaying your face onscreen in the middle of the story?

Portillo: My initial idea was to shoot someone else getting acupuncture, and it [was] only at the last minute that I decided it should be me, since I was including myself so prominently in the film. In addition, I was feeling terribly guilty about having [surreptitiously tape] recorded the conversation with Ofelia. I felt that I had broken the laws of documentary, that I had done something I wouldn’t normally do. My soundman, Jose Araujo, who used to be a seminarian, worked for 20/20. And he told me, “They do this all the time, you know, so just do it, because we don’t have anything else to go on.” So we did it. But it carried a lot of guilt. At the time of shooting the acupuncture scene, I thought, “This is the way to do some penance.”

Filmmaker: Was it painful?

Portillo: It hurt a lot. Actually, after I got the acupuncture, I fell asleep while they were shooting. I slept for about an hour, and they were waiting for me in the waiting room.

Filmmaker: The film reconstructs a certain form of late Mexican baroque. It shows in the loving way you shoot the architecture and present popular culture, but also in the way the lighting is designed. It suggests a state of mind, a certain approach to fiction.

Portillo: This was a very pre-determined choice. Before we left for Mexico, my cinematographer, Kyle Kibbe, and I decided that the film was going to have this darkness of tone, and that the lighting had to be very dramatic. It’s the kind of light you have in narrative films – to make a clear distinction from your usual vérité documentary. There is one moment when we didn’t have a chance to carefully work out the lighting – it’s in the scene with the policeman – because we had to be in and out of there so quickly… Otherwise, the lighting was entirely pre-determined. When I came back from my first trip, I showed the tapes to Kyle, he looked at them, he looked at the people and said, “This is what we can do.”

I think that in this country people harbor a lot of negative stereotypes about Mexicans – who they are, what they look like, what their reactions are, how they talk – and my intention was to get people to feel a different way. Not every Mexican is a campesino. Not every Mexican is inarticulate. Mexico is not dirty and ugly… So I wanted to give, as you say, a very baroque feeling to the whole film, so it is intricate and complex.