Back to selection

Back to selection

“We Have Regressed Into an Obtuse and Rigid Moral Order”: Catherine Breillat on Last Summer

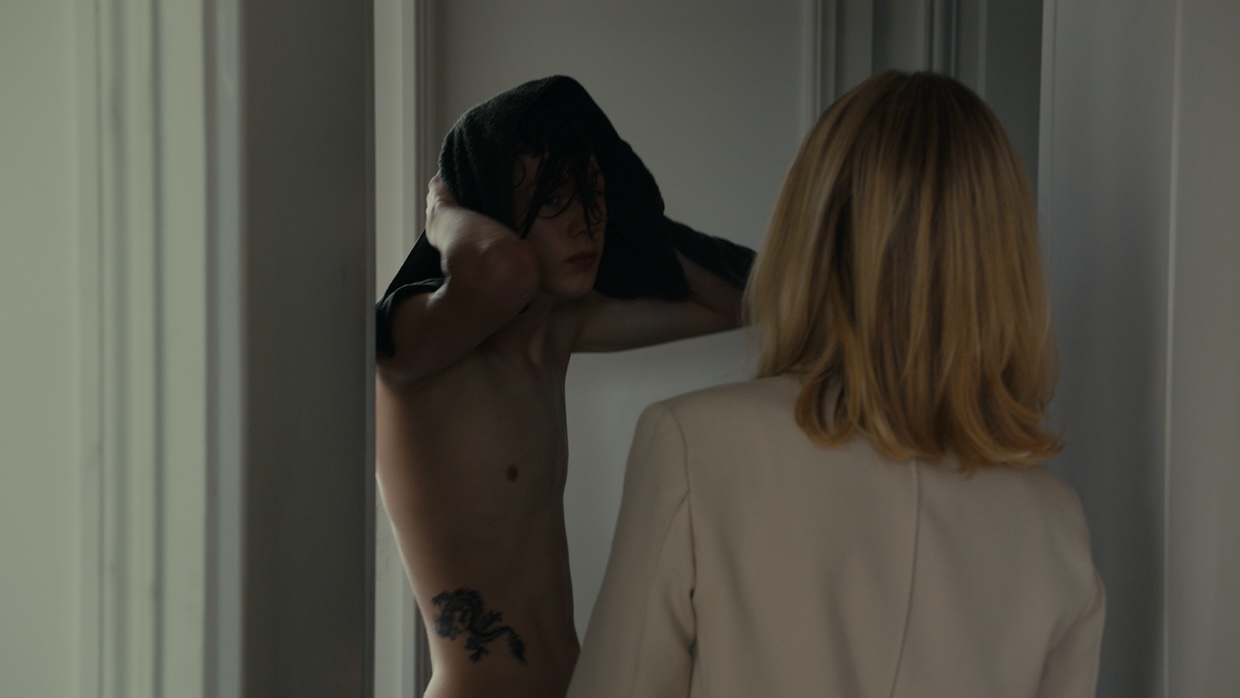

Samuel Kircher and Léa Drucker in Last Summer

Samuel Kircher and Léa Drucker in Last Summer It’s been a long decade’s wait since Catherine Breillat’s last feature, the semi-autobiographical Abuse of Weakness with Isabelle Huppert, but Last Summer shows the uncompromising French filmmaker in top form, at once fierce and precise. Returning to a favored subject—the desires and power dynamics in affairs between adolescents and usually much older adults—Breillat brings in another taboo this time: the messy sexual obsession between a lawyer, Anne (Léa Drucker), and her 17-year-old stepson, Théo (newcomer Daniel Kircher). After Théo comes back to stay at the family’s idyllic home outside Paris, the two carry on secretly until the truth becomes inescapable for her husband, Pierre (Olivier Rabourdin), who also has two very young daughters with Anne.

Before Last Summer, Breillat says she hadn’t wanted to make movies anymore and felt worn out physically. (Now 75, the director had a stroke in 2004 that left her partially paralyzed, though she continued to make films.) The idea for Last Summer came to her from Saïd Ben Saïd, who had the remake rights to the 2019 Danish drama Queen of Hearts (and, she says, suggested Drucker for the lead). But this is a Breillat work through and through, with a masterful attention to visual detail and the give-and-take of staging that—as our interview suggests—continues her subversive dialogue with centuries of portrayals of love and sex in art and cinema that date back to A Real Young Girl, her 1976 debut feature, and on through 36 Fillette, Fat Girl, Anatomy of Hell, The Last Mistress and the rest of her oeuvre. Her admirers also count many filmmakers, and here I cede the stage to Kit Zauhar (This Closeness) who shared this reaction after seeing Last Summer: “Fundamental to Breillat’s work, and what gives it its power and singularity, is that it understands that a woman’s sensuality is inextricably linked to her murky dark history (again, as most women’s histories are); that, regardless of age, her desires are fueled as much by beautiful sexy things—lust, impulse, instant gratification—as they are by disgusts, fixations, and past trespasses; that she might not even want what she’s getting in the moment, but perhaps a past or future version of herself does.”

Last Summer opens June 28, but I sat down with Breillat last October when she was in town for its screenings in the New York Film Festival. As she candidly detailed her directorial process, the twists and turns in her close readings of the film’s mise-en-scène became suspenseful and illuminating narratives in and of themselves.

Filmmaker: What were the challenges of making a new movie out of your source, the Danish film Queen of Hearts?

Breillat: No difficulty. The only challenge was to appropriate the film so that it wouldn’t be a remake and to take out the things that weren’t my style. In general, in the things that I kept, I pulled toward more emotion. The Danish film was quite cold.

Filmmaker: What were the things you wanted to take out?

Breillat: First and foremost, the thing I wanted to get away from was the raw and explicit sexual content, because, contrary to public opinion, unless that’s the subject, it’s not something that I handle. And that the woman not be a predatory woman, because a predatory woman is not something that I know or understand, and I can’t film something that I don’t know. And that the teenager be my kind of teenager, which is to say, in the kind of absolute adolescence as it exists in the French tradition through Marivaux and Rousseau, and as Rohmer was very good at representing them: that he be an agent of desire and not want to submit to the desire of another. So, the woman was seduced and not predatorial, and the teenager was an agent of desire. Also, the little girls were different than in the original film. I love filming with children, but I wanted them younger so that they wouldn’t be damaged by the schooling system. These three things were enough to really alter the spirit of the Danish film. The script was changed very little, yet the film is entirely different.

Filmmaker: You mentioned that unless sex is the subject of the film, you don’t film so explicitly. In general, I think that your earlier films, the more explicit ones, might not all even be made in today’s environment, because of their open sexuality. It’s as if things have gone in the other direction.

Breillat: In 1997, I spoke in Tehran at a conference on the place of women in cinema, the place of women’s bodies and the commodification of women’s bodies, and was expected to say what we always say on these subjects—about how we’re against it. It took me a month to write the 10 pages for the speech, and I’m not a philosopher, but today, I would like to publish the speech that I said on Iranian television, in front of the “guardians of the revolution,” because I think it wouldn’t be possible today. I think people need to understand how much we have regressed into an obtuse and rigid moral order that is without measure and without correspondence to how we actually live and what we’re actually made for so that people will be ashamed of this regression.

Now that there’s going to be a retrospective of my work here, I’m sure that a lot of people are going to think what you just said: that my work couldn’t be made anymore. With 36 Fillette, I had to prove that she [Delphine Zentout, who plays a teenager having an affair with an older man] was 16 years old by showing her birth certificate. She turned 16 three days prior to the filming. Had we filmed the film three days earlier, it couldn’t have come out in America, because it wouldn’t have been legal. This is true also for Brief Crossing: he [Gilles Guillain, who plays a teenager seduced by a woman on an overnight ferry] was exactly 16. And in this case, Samuel [Kircher] is 17, which in a way should be much older, and yet because it was shot today I had to make the central scenes a lot softer than I would have in my previous films. In Fat Girl, Anaïs [Reboux, who played the younger sister] was 12 or 13, no more.

Filmmaker: I want to ask about a particular scene in Last Summer because you take such care with the framing, the length of the shots, everything. It’s when Anne and Théo first kiss in his room. When I watched the film in Cannes, I thought of the first shot in this scene as “POV: both of them,” because they’re looking at his phone together. Could you talk about staging this scene?

Breillat: Here we were confronting the impossibility of shooting in the same set, because we already had the scene with the father when he comes and tells Théo not to smoke in the room. There are two possible camera placements in that room, and I couldn’t crack how to stage it so that the lighting would be right on Léa, who needed to be very beautiful for the desire that he has for her to be believable. Thankfully, I slept on set during the shoot, so at night I would walk around this very small room again and again, trying to find a solution so that we could light her accordingly. Actors are beings of light and we make them according to our imagination. I get up one night and walk around and have this idea of this radical shot which is preceded by a shot of Samuel in close-up, where we see how he’s looking at her and see the desire that he has for her. Then we found this way, by pulling the bed forward, of putting the camera at their backs in such a way that we could see the cartoon [on his phone], because I wanted the cartoon to be seen. But we couldn’t cut to it—that would have been a grotesque editing move. In this way, by being at their backs in this very radical and slightly unreal point of view, we made it so that you could barely sense the movement of the shoulders and bodies, and that we wouldn’t feel him moving towards her first even though it’s his initiative, but that it comes to be in this moment as though they have had this tacit agreement that comes to a breaking point and they turn for this interminable kiss.

Filmmaker: The sequence is a good example of how you tend to use long takes when you film intimate scenes in this movie. There’s another powerful moment later when you hold the camera on Léa after they have sex. She looks like she’s in another world, and it’s almost the longest part of the scene, capturing her state of being. I wonder if you can talk about filming that scene but also generally how you filmed such intimate scenes.

Breillat: So, the first love scene was the only scene where we were going to see Théo like that. To do that, we had to raise the bed—we needed him to be on top and, in this very, very beautiful sense, for him to be active. It’s the only time where we see him come. And it was important that he came for her, not the other way around in this scene. Also, after the scene, his demeanor is that it’s not that big of a deal, everything’s fine, there’s nothing so dramatic about having slept together, because he thinks that feelings aren’t his thing. This is important to show his sexual background.

In the second scene, we see that they break the promise that they have made to each other and that what they have is in fact a true affair, that there is a kind of belonging of their bodies together, and that something has brewed between them. Again, it was a difficult scene to imagine, and ideas always come to me at night for scenes that I’m afraid of. One night for some reason I had the idea to go and see Caravaggio’s Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy, and it’s really in seeing this painting that I was provided with Léa’s character. There is also a painting of a naked woman above the bed who has her neck kind of curved on the side. For me, this curve to the side is the conjugal kind of love, right? That’s the way that one sleeps with one’s husband. It’s very good for the camera also, because it’s very beautiful, but it’s very different than the arched neck that goes from the top of the skull that that we see in Mary Magdalen, and that is the sort of ecstasy that we were seeking to achieve in that moment. It’s really thanks to this painting that we found Lea’s character, and she became kind of a Hitchcockian woman in her coldness and her frigidity. When she does come with her husband, she still does so with kind of a tight fist. All of these nuances came from this inspiration.

I told Léa, “If that’s how Caravaggio did it, you must be like that too.” It was very difficult to make it all in one shot because we wanted to get Samuel’s line when he says, “I’m making progress, I’m getting better at it.” It might seem that the scene with the two legs is easy to do, but it’s really very difficult to find a way for the rest of her body to disappear so that we don’t have her breast or things coming in the foreground. So, she had to hold very acrobatic positions, yet still make it beautiful and natural. It was a whole thing for Jeanne [Lapoirie], who’s the DoP, to find a way to work with the reflection in the mirror that is behind the bed, that has both a kind of normal mirror plane and then a Venetian mirror plane on the side. That could become too Hamiltonian, maybe a bit too Baroque. So, there was really a merciless choreography that they had to learn, and Léa was very glad when I told her that we had found the scene. I had tried it with my body first, which I always do, then tried it with my assistant’s body, then tried with the sound engineer. But that’s still different than doing it with the actors who have a morphology of their own that is going to dictate the frame slightly differently.

They needed to integrate all of that, to act naturally the artificiality of the situation they’re in. That’s true also for Jeanne and the focus holder and the person working with the camera, who also all have to rehearse to have the kind of dance movement that we want to stay close to this love scene, and how to work with the mirror in the background. We did it many, many times, and it was good but something was missing. I did one last take, and it was starting to get very warm and we had been there for a very, very long time. It took three hours altogether maybe to film but also to prepare, and the scene is very long, so when you start it again you’re going for a while. I couldn’t tell what was missing, but first it was something to do with the way that her eye drooped, which was already good, but I still wasn’t sure. I was starting to be embarrassed, because maybe I already had the take and was looking for something that couldn’t be achieved.

Still, I committed to the feeling that something was missing. Eventually, I just thought that I didn’t want to see Samuel anymore. Samuel was too beautiful and was ruining the shot and just needed to get out of it entirely. So, we shot it again while making Samuel disappear, and it was good but something was still missing, and I couldn’t get what it was. I was getting bored somehow, sitting behind the monitor, and suddenly I think of Mary Magdalen! And I remember that before the painting was called Mary Magdalen in Ecstasy, it was called Mary Magdalen Buried in the Grave. So, at the last moment, I started to say to Lea, “Die, die, die right now!” And even though she had had this very, very subtle progression of pleasure, there was the moment of death, which got the scene to the point that I had wanted to take it.

Filmmaker: Léa Drucker is incredible in this scene, which is not easy. Not every actor can be good at acting in a sex scene.

Breillat: And it’s her first time. In France, she’s like the girl next door. It was something she was really afraid of. But she loves cinema so much that she took the risk and said yes.

Filmmaker: She’s also so adept at playing this character, a lawyer who knows the facts but who’s keeping up the lies and pretenses involved in having this affair and concealing it from her husband.

Breillat: The whole time, Anne is annihilated by the idea that her husband is going to find out. Even when that happens, she hopes until the very, very last minute that he doesn’t know. In the moment of the revelation, the moment where he says he does know, she becomes “statue-fied”—she becomes like a statue. And it appeared to me that, from that moment on, she became a Hitchcockian character. I said, “Kim Novak. You do nothing, nothing at all.” It was very important to me that this almost stone-like quality be there, because the point is for us to love her irrationally, even if we don’t understand her. Her husband comes toward her with his very imposing stature—he’s much, much taller than her and dominates and towers over her. And he says, you’re saying nothing. I said [to Drucker], “You say nothing.” At some point in one of the takes, she started to cry. And I said, “No, not at all. Tears are a confession.” But she did need to get up [from sitting], so I told her to get up, but I said that cinema is really not about speed, it’s about slowness. So, she had to get up in this extremely slow way that her eyes would be the first thing to be raised in this expressionist way, so that by the time that she is standing her face is completely transfigured. There’s a whole journey in the way that she goes from sitting to standing.

It was very important once she gets to that point where she can start to speak that she play without fury, because the lines were terrible enough that she didn’t need to spit them at his face. So, she stays—and this is true for a lot of times in the movie—present and mysterious through the gaze of the person looking at her. We don’t actually see her all that much so much as we see her being looked at by a person wondering what happened; in this case, her husband. When he gets to that point of saying that he knows details that couldn’t have been made up, which is the moment where she can’t lie anymore, then she needs to leave, because that’s where the possibility for lying ends. So, she just needs to go and start attacking him, because attacking him is the best defense at this point.

Filmmaker: How might this drama be different if it’s reversed to be an older man and teenage girl?

Breillat: It becomes 36 Fillette.

Filmmaker: I want to jump earlier a bit to talk about Kim Gordon’s music, which you feature. When she started her band in 2022, Body/Head, she said she named it after reading about your movies. Can you talk about collaborating with her?

Breillat: Kim Gordon came to Paris because she didn’t quite understand what I wanted, because she doesn’t work as somebody who scores for film. In general, I like songs but wanted a specific kind of vibration that she wasn’t quite understanding. So, she saw the film and we talked. I love rock and roll, and it was reciprocal: I actually found out [that she liked my work] after finding a book at the cinematheque of Vienna on me and my work by Douglas Keesey, published by Manchester University. Finding this book was really incredible, almost like reading my own psychoanalysis. There were details in it that I didn’t even understand how they had gotten—about my sister, where I grew up, my assistant that I used to call “my damned soul.”

It was truly fantastic, and I wanted to reach out to him. He teaches in the U.S. now so I wrote to him, and he wrote back and told me that Kim Gordon very much loved my work. In an interview not unlike the interview that we see in the film with the voice recorder, she was asked what she would have wanted to take on a desert island and answered with this book on Catherine Breillat. So, I told my producer, who only wanted to buy one of her songs, that it was very important to me that I get in touch with her and find her agent. The next day she replied to me, and that was really the miracle that the film needed.

Filmmaker: So there were songs of hers that you already liked?

Breillat: Yes, of course. There were some songs I had liked of hers that I had forgotten, so there was a kind of renewal there too. She’s also a filmmaker, which I found out after she invited me to a set of screenings at the FIAC, where her films were by far the most interesting. They’re art films, a bit like Chantal Akerman’s.

Filmmaker: Are you working on another project?

Breillat: I have so much difficulty making my projects begin in the first place that maybe I shouldn’t say so much. There was one I had prior to working with Saïd Ben Saïd, but Saïd is such a great producer that I struggle to imagine working with someone else beside him. We will see. But there are many ideas. I saw Léa Drucker and Isabelle Huppert at a screening organized by Le Monde. Seeing them together, I did have the idea that, both of them being my actresses and each being as incredible as the other, they might maybe want to play sisters.

Filmmaker: One last topic we hadn’t discussed was class and how that plays out between Anne and her husband and within the family.

Breillat: Yes, we can feel that, thanks to the character of Anne’s sister, she might not come from the same world as her husband, but she has made her money in her own right as a great lawyer.

Filmmaker: Despite everything between her and Théo, she feels this duty to protect and preserve the family perhaps more than anyone.

Breillat: It’s a “Sophie’s choice” kind of situation: did Sophie love her son or daughter more? She doesn’t have a choice but to try and save her family—and also to save this conjugal love, which isn’t nothing. The marriage is not nothing in this situation. She makes the tearful choice to defend the family—in French, the family unit is called the cellule familiale, like a living cell. And although it becomes kind of opaque, and although it is a point of privation of freedom, it remains the structure of one’s entire life, to build a family. But this impossible love comes to disturb that, and real as that is, when she is put in that situation she defends her family with everything she has.

Filmmaker: And yet your film never felt to me reliant on narrative intrigue.

Breillat: Never, eh? It’s based on emotions and the intimate reality that people never film. They don’t know how.