Back to selection

Back to selection

The Future Looking Back At Us: Joanne McNeil on Cyberpunk

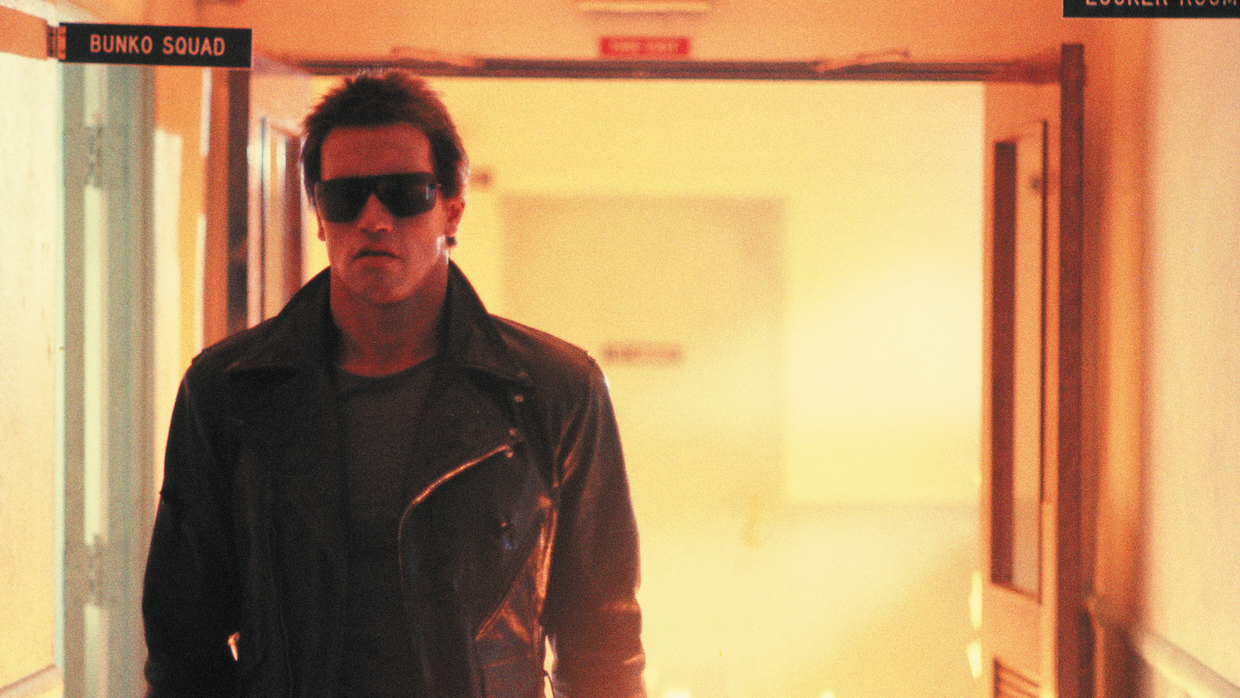

Still from The Terminator (1984) Courtesy of MGM Media Licensing. THE TERMINATOR © 1984 Metro-Goldwyn-

Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved

Still from The Terminator (1984) Courtesy of MGM Media Licensing. THE TERMINATOR © 1984 Metro-Goldwyn-

Mayer Studios Inc. All Rights Reserved This year is the 40th anniversary of William Gibson’s classic novel Neuromancer. It’s a work of singular brilliance that arrived as part of a new vanguard. Back in 1984, in the Washington Post, author and editor Gardner Dozois identified Gibson as part of an emerging trend: new science fiction authors who had eschewed formulaic space operas for “bizarre hard-edged, high-tech stuff.” Dozois called these authors the “cyberpunks,” and the label caught on.

Key works of cyberpunk like Neuromancer were produced in the ’80s alongside the boom in personal computers, and again in the ’90s as subscriptions to online services and sales of modems took off. Now, in reality, two-thirds of the planet has access to the internet, and virtual worlds are no longer the domain of “console cowboys,” but, curiously, cyberpunk is still often referenced as a living rather than retrospective category. What is it about cyberpunk that has endured?

Jared Shurin, editor of The Big Book of Cyberpunk, published last year, argues that the “legacy of cyberpunk remains not only relevant but ubiquitous.” His anthology, spanning more than a thousand pages and organized with great care and ambition, gathers writers from the first decade of cyberpunk, like Gibson, Bruce Sterling, Neal Stephenson and Pat Cadigan, and puts them in conversation with emerging science fiction authors like Wole Talabi, Madeline Ashby and qntm.

Another recent work of curation, “Cyberpunk: Envisioning Possible Futures Through Cinema,” which opens at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures in October, likewise has a program that spans from Blade Runner (1982) and Tron (1982) to recent films including Neptune Frost (2021), Alita: Battle Angel (2019) and Night Raiders (2021). Filmmaker Alex Rivera (Sleep Dealer, 2008) was commissioned to write an original script for the exhibition.

Both the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures exhibition and The Big Book of Cyberpunk approach “cyberpunk” expansively to highlight recent work by diverse talent around the globe. Introducing the anthology, Shurin writes, “core cyberpunk was demographically homogeneous” and that tunneling the genre to the future, rather than looking back on it, is an attempt to “capture how many writers from many different backgrounds—demographic, geographic and artistic—took on the challenge of writing about our relationship with technology and one another.” Likewise, in the exhibition catalog for the “Cyberpunk” show, curator Doris Berger writes that she intended to highlight classic cyberpunk work as well as newer films with “characters and stories about people of color, women,and members of the LGBTQ+ community.”

Attempts to gather a less “demographically homogeneous” cyberpunk movement are as old as cyberpunk itself. Fanzines published essays like “Cyberpunk In Cuba” by Cero Uno, highlighting authors working outside of the mainstream in unexpected regions. When Gibson’s Burning Chrome was published in 1986, the writer Jeanne Gomoll, in an open letter, expressed irritation with Bruce Sterling’s introduction to the story collection. Sterling had characterized the previous decade of science fiction as “confused, self-involved and stale.” Gomoll countered that he had “whisked under the rug” the radical advances in the genre by feminist writers. Some of those feminist writers in the ’70s, like Joanna Russ and Marge Piercy, detailed proto-cyberpunk body modifications and technologies to jack into new realities. Their fiction would inspire Donna Haraway, who published A Cyborg Manifesto, a work of theory with themes simpatico with cyberpunk, in 1985. There’s an expansive history beyond cyberpunk, but a project like The Big Book of Cyberpunk branches outward from narrow roots instead of incorporating it.

William Gibson himself said he “winced” when he first heard the word “cyberpunk.” He was older than the other writers in the cohort—36—when Neuromancer was published in 1984 and went along with the label as an “uncomfortable passenger,” he told the BBC World Book Club in 2015. Funny thing is, if cyberpunk still feels alive and well, 40 years into the future, you’ll find the reason why in Neuromancer.

As the cyberpunk fan zine Cheap Truth put it back in the ’80s, Gibson “concentrates on surfaces as a way of getting at essences.” You can see, in some of the finest sentences, how the rhythm of Burroughs rubbed off on him and where Ballard’s spatial (directional, rather than “inner space”) obsessions were an influence, but Gibson’s writing is always lucid, never surreal. Machines in his novels are plugged into something; things happen for a reason; alienation, rather than madness, is what animates his characters. They are users of software and hardware and data systems, in cities and networks of infrastructure, siloed before connecting with others through networked machines.

Rereading Neuromancer over the summer, I was dazzled anew by the author’s uncanny prose—how Gibson wrestles technical jargon, the stuff of developer documentation and instruction manuals, out of its familiar contexts to create a neon mood of intrigue. We all know how the book opens (“the sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel”) but another evocative line, just as stunning, happens a few pages later, as the protagonist Case is thinking about his lost love, Linda Lee. He remembers “her face bathed in restless laser light, features reduced to a code: her cheekbones flaring scarlet as Wizard’s Castle burned, forehead drenched with azure when Munich fell to the Tank War, mouth touched with hot gold as a gliding cursor struck sparks from the wall of a skyscraper canyon.”

An arcade is a setting that readers in 1984 would have been well acquainted with, but Gibson writes about what’s happening on that floor like the future worlds in the same book. Elements of his style are consistent across the book and his body of work. His writing is highly visual and granular, with fastidious attention to design and spatiality. The first novel he published in the new millennium, Pattern Recognition (2003) is set in a present that reads like science fiction; likewise, his work set in the future reads like realism of that future.

Gibson has said in multiple interviews that he got the idea for “cyberspace”—appearing first in his short story “Burning Chrome” and expanded in Neuromancer before there was much of an internet to speak of—after watching kids in an arcade, rapt in gameplay, looking like they’d like to climb inside those blinking and dinging cabinet machines. In Neuromancer, he captured the hunger to experience that technology and the all-consuming attention of being jacked in: how technology can get inside you, change you and leave you hungry for more. That was happening in the arcades, and it is happening in our digital experiences 40 years later.

While the cyberspace of Neuromancer is so vastly unlike what the internet has turned out to be, Gibson writes like he lives there—even reading it today, you believe him.