Back to selection

Back to selection

“In a Way This Film Asks, What is Lost by the Virtual?” Ira Sachs on his Sundance-Premiering Peter Hujar’s Day

Peter Hujar's Day

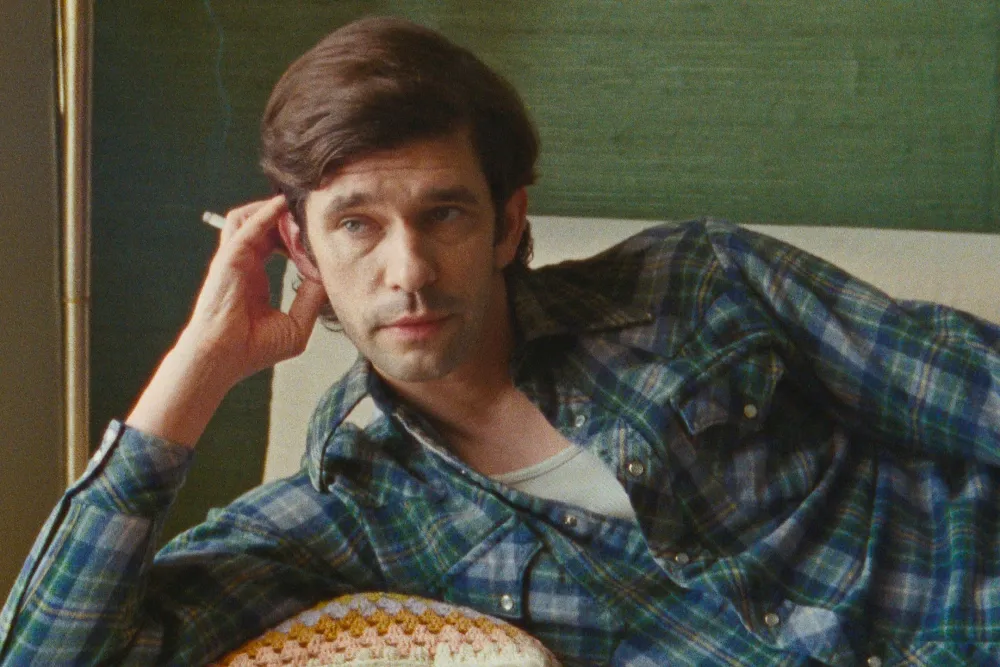

Peter Hujar's Day Among the features premiering this year at the Sundance Film Festival, there are none — on paper — simpler than Ira Sachs’s Peter Hujar’s Day. Arriving just two years after he premiered his Passages at the festival, Sachs reunites with actor Ben Whishaw for a picture that’s one 76-minute dialogue between two friends in a New York apartment in 1974. What’s more, that dialogue is not some dramatically sculptured theatrical two-hander building to third act epiphanies but, rather, a transcription of an actual conversation between art photographer Hujar and artist Linda Rosenkrantz, who was conducting interviews for a book in which New York artists would, Andy Warhol diary-style, narrate the details of one 24-hour period. (That book was abandoned but Hujar’s conversation was published as its own publication, Peter Hujar’s Day, in 2022.) Hujar’s day in question involved traveling a few blocks to poet Allan Ginsburg’s apartment for a New York Times photo shoot, his first for the paper; snacking at McDonald’s; dinner with friends; and contemplating various professional issues, such as whether he could get Susan Sontag to write an introduction to his forthcoming monograph.

But the above description belies the sophistication and, well, pure cinema of Sachs’s film. Freed from having to hit pre-determined plot points, dramatic reversals and climaxes, Sachs and his actors capture something more sublime, a flow of intimacies, recognitions and realizations that speak to qualities both timeless and very specific to their era. For a shoot that stretched from day until early morning, cinematographer Alex Ashe (a 2024 Filmmaker 25 New Face) films in Super 16mm and lovingly captures the play of light and shadow on the actors’s faces, forming an unspoken dialogue with the theme of portraiture, a constant in Hujar’s creative life. Stephen Phelp’s rich production design of Rosenkrantz’s apartment connects this dialogue to the aesthetic trends of the era while Affonso Gonclaves’s sensitive editing captures not simply the subtlest dramatic shifts between the actors but the feeling that their conversation is suspended within a larger sense of time passing.

Whishaw is extraordinary in Peter Hujar’s Day and in his recreation of the photographer entirely different than we’ve ever seen him before. While remembering and then reciting the quotidian events of these hours, through his delivery he also conjures moments of poetry, philosophy and reflection. And then there’s Rebecca Hall. Great actors are often judged not by their ability to orate a stirring monologue but by their ability to sensitively listen on screen. As Rosenkrantz, Hall’s page count is much smaller than Whishaw’s, but she makes her artist character a compelling equal, constructing, as Sachs says below, a storyline existing entirely between the words of this 51-year-old encounter.

Below, I spoke to Sachs about his approach to adapting Rosenkrantz’s slim tome, what his film has to say about the artist’s life in the 1970s and now, and the classic independent short films that influenced the making of Peter Hujar’s Day.

Peter Hujar’s Day — for me, one of the best films at the 2025 Sundance Film Festival — is seeking distribution.

Filmmaker: In the press notes you talk about reading the book Peter Hujar’s Day while in prep on Passages. Is it important to you to have multiple things going? A surety of what you’re doing next?

Sachs: When I read it, I felt like, “Oh, this is on a scale I can make, and I can imagine making it soon.” And I’ve been following and been moved by Hujar’s work for probably 20 years now. Also, I had the beginning of this relationship with Ben [Whishaw] that felt very fertile and personal. We’re actually working on the third film to shoot this summer. So, it’s a particularly rewarding collaboration, and I think there are a lot of reasons for that. The way we approach filmmaking is as part of an interest in art and creativity, subculturally and experimentally. And then there was the success of Christopher Munch’s The Hours and Times —I don’t know a better film about the experience of being an artist that that movie. So, I felt like I knew the potential of something scaled at a [similar] level. And, very specifically, when I got to the last page of the transcript, I was very moved. So, in a way, that was a challenge – I needed to make a film that pulled that off as well. But while it was an interesting conceptual project, it wasn’t obvious how to approach it. Once everything was in place, which happened quicker and easier than most, I was like, now what do I do ?

Filmmaker: I remember talking to you once about Rachel Cusk’s Outline, a book we both love. You told me you were interested in adapting it but then you realized that you didn’t know how to make it as a movie.

Sachs: You know, I tried again. [Rachel and I] have become very good friends, and I was working with Rebecca Hall. I thought, Outline, Rebecca Hall, Rachel Cusk – this makes a lot of sense. And I just couldn’t do it. The book was complete. And I think [Peter Hujar’s Day] felt not incomplete, but open. But I did have a moment that was somewhat similar, when everything was set up. There was a bit of a crucible for me because I wasn’t certain what to do with it. Having come off Passages, which for me was an action film, I wanted to continue to make films that understood cinema as a form of suspense and movement. And yet I had this text, which was very static, so the challenge was to break it open, to kind of crack it.

Filmmaker: And how did you approach this challenge?

Sachs: Two things happened. One is I started to explore a bunch of films that were made in the ’60s and ’70s that had done that successfully, that were very intimate and simple but also had cuts and ellipses and movement and changes of scenery. And [the second] was to trust a simple film. Portrait of Jason doesn’t have all the things I just described, but Jason allows me to say, “If you do this well and right, and clearly and directly and rigorously, there can be a huge amount of meaning in this simple form.” So, trust the minimal.

Filmmaker: What sort of structural elements did you add to the text? As you say, there are so many location changes within this one apartment as well as gradations of light that change throughout the day. And speaking of the performance, there’s a feeling through Ben’s delivery of time passing, of the rhythms of the day.

Sachs: The introduction of a 12-hour period, from late afternoon until dawn, was what I introduced to the material.

Filmmaker: How many hours was the original interview?

Sachs: I don’t know. It doesn’t exist as audio. But that was something I had done in [the short film] Last Address, which also completed a day. That was imposed upon the idea, and it had given it movement and narrative, so that was what I introduced [here]. And then [I had] the experience of being in the space for a couple of months and the opportunity to shoot the stand-ins at different times of the day in different corners of the room. And ultimately, those images in a row told me what the film was. Suddenly I was like, oh, that’s the film. That’s it. It’s a series of portraits that are based on questioning or examining the relationship between figure, space, and light.

And then it became a conversation with Hujar that was unexpected for me around the emotion and the psychology that comes out of looking in a very direct way at bodies and people. How do you change or manipulate that based on artistic craft elements like grain, shadow, overexposure or daylight? There’s a whole other narrative that’s going on because of that. I never approached the space based on the text itself. It was basically like, “Now we need to move to a new location,” and that wasn’t because they were talking about [something specific related to the location]. I never thought of it that way. So, there was all this accident — like, what happens if you put this text on the terrace? What happens to the text? It becomes totally different because you placed it there. And it was about pace, film rhythm, and how long a shot could hold. I was working with issues of duration, but I didn’t want to make a film that pushed that too far.

Filmmaker: One of the throughlines in the text is Peter’s relationship to his subjects. There is this ineffable quality he seems to be searching for. He’s dissatisfied with the Allen Ginsberg photo because he thinks maybe Ginsberg wasn’t attracted to him enough, or there was some other thing going on that day. And then your film is really just about this intimate relationship between these two performers.

Sachs: That’s right. I think “performers” is a good word. They’re both characters, people and performers. And all of them are interesting to me. The nature of performance in both Ben and Rebecca, what they do in the moment, is what I enjoy watching the most.

Filmmaker: What was surprising to you about what they brought to it? I understand you don’t rehearse.

Sachs: I think that Ben revealed that he could make everything have specificity and meaning while simultaneously being extraordinarily fluid emotionally and textually. Rather astonishing. And I think Rebecca understood a story between two friends that I followed but I didn’t write. She really wrote that story.

Filmmaker: Interesting. They do come off as intimates.

Sachs: They come on an intimates, and also you see a romantic friendship that I think is very singular but also very familiar, the particular relationship between a heterosexual woman and her gay male artist friend. I think I saw my own relationships in that friendship.

Filmmaker: A moment ago when you talked how long shots could be held, was that something you were discovering in the moment, on set? Or did you have that mapped out?

Sachs: The whole film was storyboarded based on time and what kind of light we wanted. We had to construct a schedule that gave us those opportunities. We often went back at the end of every day to the golden hour.

Filmmaker: Were you shooting out of order?

Sachs: We were shooting out of order. What I couldn’t do based on the monumental amount of text was make changes about what we would shoot any one day. We had to shoot what we said we were going to shoot. We couldn’t add anything because the daily prep became, for Ben particularly, around a certain amount of text. He knew all the [screenplay’s] text, but he couldn’t have all the text ready every day. So that was kind of a discovery about what was necessary. I needed to support the fluidity of his relationship with the words by not putting too much on top of what I was asking of him.

Filmmaker: I understand your sister Lynn gave you a list of 25 experimental films about a person’s camera. What were some of those films?

Sachs: An Image by Harun Farocki was really exciting to me. Poor Little Rich Girl by Andy Warhol, which is Warhol with Edie Sedgwick at the Chelsea Hotel. Portrait of Jason. And Christopher Munch actually recommended a film which was probably the most important to me — Jim McBride’s My Girlfriend’s Wedding, made just after David Holtzman’s Diary. It’s a portrait film of his girlfriend, Clarissa, who was getting married for green card reasons, but much of it is just Jim and Clarissa in an apartment talking and it’s a great 30-minute film. I think the energy and the rhythm of that film and the use of ellipses [related to Peter Hujar’s Day]. Two images, for example, on the terrace, are pretty much direct recreations of Clarissa on the terrace. And part of that [influence] was [realizing] that if you focus the camera in a certain way, it will look like 1974 just by the buildings you pick. So, it was sort of tricks of the trade, I guess, and also permission to trust that the audience could contain the non-sequential narrative tropes of the movie.

Filmmaker: What do you mean by that?

Sachs: That it isn’t sequential. We don’t see how people get from one place to the other. And that was really a big break because if I had to figure out how they get from the living room to the terrace, that would have been a disaster. I needed to use the cut. The cut was my friend.

Filmmaker: Is all the text from Linda Rosenkrantz’s book, or did you add to it?

Sachs: I found the transcript for her book in the Peter Hujar archive at the Morgan Library. And I realized that in publishing the book, they had actually taken out some things that felt like gold, so I brought those back to life. In way, though, that’s what the whole book is — something brought back to life. For example, the conversation about Betty Davis and Joan Crawford is not in the book. We also took things out based on pace. It was important obviously to be rigorous but not to be fascistic about my relationship to the original text.

Filmmaker: What about the recorder’s presence on screen? Sometimes it’s very clear that the words are being recorded, and in some setups the recorder is off screen, and I wondered whether it was even supposed to be there.

Sachs: I felt that the audience would loosen up, and they understood the concept of the recording and it didn’t always need to be realized in a literal way.

Filmmaker: It’s a very small, contained film, 76 minutes, but at the same time, and from looking at both the film and your credits, I can tell it’s not a microbudget film. I think sometimes people think that a film with two people talking in an apartment should cost some incredibly tiny amount, but you obviously knew you needed more resources than a microbudget budget.

Sachs: Well, you know, it’s a feature film, so that comes with a lot of demands, and it comes with certain expectations, financially. We were also in that space for about a couple of months. We had an extensive period of prep, the film. But, we had these wonderful financiers and producers, who really understood the nature of the film, and they gave me a lot of freedom.

Filmaker: One of the things I really took away from the film and the experience of sitting with these two artists is just a contemplation of how the life of the artist has both changed since 1972 and is also very similar. Obviously, this is pre-internet, so I felt a different rhythm of the day. Like, Hujar is trying to make a phone call to Allan Ginsburg, and the line is busy, so he goes downstairs to pick something up. There are those pockets of dead time that occurred because you can’t do what you want to do as opposed to today, when you’re just in this constant flow and answering five emails and texts all at the same time.

Sachs: I think the film draws attention to the monumentality of time. And I think that’s what I experienced when I read the book also. By the fact that the book existed meant it put shape to time that is lost.

Filmmaker: The film also meditates on what counts as cultural capital, or prestige. He’s talking about the Ginsberg shoot as his first for the New York Times and whether or not he’ll sell more books if Susan Sontag writes the introduction.

Sachs: I think the film and Ben’s performance gives voice and makes visible the want in an artist’s life. There’s so much desire that never gets sated and that is not in general visible to the world, right? I keep thinking about the Cedar Tavern, which serves as a metaphor for the community that existed in the ‘50s for artists in New York. In this film, the number of people who dropped by, and the number of people he talks to on the telephone in the course of one day, speaks to a kind of flow that people had between themselves that doesn’t really exist today in the same way. That seems to be what’s gone. For me, being with other artists is necessary to sustain a belief that I can keep going. In a way this film asks, what is lost by the virtual? I was talking to John Kelly the other day about the suburbanization of art making, which is the concept that the work should move you up the ladder and which, obviously, was an issue for Peter Hujar also. It’s not like he didn’t want to make money, but the expectations of the kind of money he might make were very different than today. And that introduces the question of globalization. How does an art scene get transformed by global opportunity? Which ends up being neutralizing a lot of the distinction that might come out of that scene.

Filmmaker: Tell me a bit more about what you mean by suburbanization.

Sachs: That’s what John told me, but it’s Penny Arcade’s word. I think of it as this idea that you could leap from the bohemian to the bourgeois, which I think is a desire for most artists historically, but it was less possible, in a way, for someone like Peter Hujar, and I think that meant that the work itself was more personal and more risky because it was more singular. But I don’t want to be nostalgic. I just want to say that swhat is the same and what has been lost, those are the kinds of questions that the film introduce.