Back to selection

Back to selection

“It Took 31 Years”: Zeinabu irene Davis on Compensation

Compensation

Compensation Because I had loved so deeply,

Because I had loved so long,

God in His great compassion

Gave me the gift of song.

Because I have loved so vainly,

And sung with such faltering breath,

The Master in infinite mercy

Offers the boon of Death. — “Compensation” (1906) by Paul Laurence Dunbar

Zeinabu irene Davis’s Compensation (1999) tells dual stories of pairs of lovers (both played by Michelle A. Banks and John Earl Jelks) at the beginning and end of the 20th century. The film is uniquely attuned to deaf culture, American prejudice and two distinct pandemics. Creative in her use of a modest budget (often utilizing archival black-and-white photographs to help set the scene), Davis’s unwavering determination in getting Compensation completed and presented to a wide audience has helped sustain interest in the project some 25 years after its first public screening.

At the 2000 edition of Sundance Film Festival, The New York Times‘ Rick Lyman correctly predicted that, while its artistic merits were considerable, the commercial prospects of Compensation would prove minimal. The filmmaker felt the same:

“Let’s face it, it’s not the sexiest film to sell here,” said Ms. Davis. Several dozen audience members had remained after the late-morning screening at the Park City Library Center and were asking intricate questions about her artistic choices and the research she had done. There were no distributors or celebrities in sight […] Geoffrey Gilmore, Sundance’s co-director, said of Ms. Davis’s project, ‘It may not be the kind of film that is going to start a bidding frenzy, but it’s the kind of daring, innovative filmmaking that should be part of this festival.’”

Educational and community screenings licensed through Women Make Movies soon followed, and that was primarily that.

Compensation has now been digitally restored in 4K and is in the midst of an extended theatrical run via Janus Films before making its home video debut in the Criterion Collection this summer, I spoke with Davis over Zoom about working with deaf performers, creating a period piece on a budget, and how she chose to honor her family members with this film.

Filmmaker: There are several different entry points one can use to discuss the project’s origins. Paul Laurence Dunbar’s poem [the African-American poet passed away from tuberculosis in 1906] factored into an earlier short you had made co-starring Asma Feyijinmi and John Earl Jelks, A Powerful Thang (1991), about a dancer losing people in her community to AIDS. That poem inspired [screenwriter] Marc Arthur Chéry to write Compensation, is that right?

Davis: Yes, but when Marc (who happens to be my husband) wrote the original screenplay, it was only a 28-page script which he left on my side of the bed when I was away attending a film festival. I came back to find his script as a present. A script is the best kind of present; forget about diamonds and furs and all that kind of stuff—give me a script.

We had been asked to sit on a grant panel for ITVS when it [was based] in St. Paul, Minnesota [Independent Television Service was founded in St. Paul in 1991] and while we were there, we noticed Michelle A. Banks’s picture for a [theater production] in the local free paper. My eyeballs were almost falling out from reading all of these ITVS grant applications and Marc and I just wanted to [get away for a bit] to see some theater. Thank God we did! We went to a local production [of Black Women Stories: One Deaf Experience] and Michelle was a force of nature. She had such a strong magnetic personality and charisma about her, and I think that also comes through on the screen.

Marc and I did the stalker thing where we waited for her until she came out from backstage, because we really wanted to meet her. I had a piece of paper and a pencil which I used to communicate with Michelle, as I didn’t personally know any sign language and we didn’t have any interpreters around who could assist that evening. Marc and I asked if she’d be interested in [appearing] in a film, and Michelle said “yes”; we told her that we’d send her the script and she could let us know if she really wanted to do it. Michelle eventually read the script and agreed to participate, working with us in adapting the screenplay to be more inclusive of deaf culture and deaf experiences. I made a significant effort to try to learn as much about deaf folks as I could, attending sign language classes in Chicago and befriending folks [in the deaf community]. Michelle introduced me to Christopher Smith, who is in the film as the character Bill Young and who is a dancer still performing today. They each accepted me into their world and introduced me to folks in the National Black Deaf Advocates (NBDA) group. We would send the script to them and have conversations about how to make sure that we were making the film as inclusive and as authentic as we possibly could given the limited resources we had as independent filmmakers.

Filmmaker: So the choice to have a deaf performer as a co-lead only came about due to wanting to work with Michelle?

Davis: Yes, totally. I had no family members nor any prior experience with deaf folks other than seeing the [all-woman, African-American a cappella ensemble] group Sweet Honey in the Rock perform. They always included deaf or sign language interpretation at their concerts. But that’s the only thing I knew about deaf culture.

Filmmaker: Marc has previously mentioned that the Marlee Matlin-starring Children of a Lesser God (1986) featured some insulting errors to the deaf community. In what ways were you mindful of not making similar mistakes?

Davis: During production, I think the biggest thing for us was to make sure that we communicated and talked directly to the deaf person, not the interpreter. That’s a big faux pas that a lot of hearing people will do: they’ll talk to the interpreter rather than look at the deaf person. But no: while the interpreter is the person’s tool, the deaf person is who you’re directly speaking with, so remember to maintain eye contact with them. That’s the one thing we made sure all crew members, regardless of if they were just providing lunch for the day or were a production assistant or the cinematographer or a gaffer—everyone had to make sure that they knew to speak to the person directly.

As far as compositions were concerned, we knew that Michelle spoke with her hands. Her hands are her voice, so it was important that we keep the shot compositions wide enough. If we wanted to do medium close-ups on Michelle when she was using her hands to speak, we had to make sure that the framing didn’t cut her off. Most American or Hollywood films have a tendency to use big close-ups all the time, but in our case we couldn’t do that. We could only using close-ups when we were focusing on non-verbal language happening between the characters. We didn’t suffer from shooting a lack of close-ups, just that we had to strategically storyboard and plan for when it was appropriate. My cinematographer Pierre H. L. Désir Jr., who’s basically like a brother to me, paid close attention to things like that. We had the kind of relationship where we could tease each other and say, “Look, you didn’t get that shot quite right. Go ahead, do it again, knucklehead.”

Filmmaker: I was curious how your use of American Sign Language changed depending on the decade a scene was set in. Surely you couldn’t have relied on Michelle to bring an entire century’s worth of ASL knowledge to the table, right?

Davis: No, but Michelle studied all [of that] and did her research, interviewing older deaf people to find out how signing would’ve been used by deaf people in earlier times. As a Black woman, Michelle also wanted to know how Black people signed differently than [deaf] mainstream culture today. What makes the signing different, what makes them unique? Michelle was such a great performer and found some fascinating stuff to incorporate into her performance, keeping her hands closer to her face when she signed in the period section of the film, then using more of her body and the physical space around her in the film’s contemporary section because, by the time we get to the section set in the 1990s, sign language had historically evolved quite a bit. Michelle taught us, as a crew, about the wonderful nuggets of history she had learned and how she was planning to incorporate this knowledge into her approach to the [two] different characters she was playing, Malindy and Malaika.

Michelle and John [Earl Jelks] really worked in tandem. John would listen, sure, but he learned sign language too. He would pay attention to what Michelle was signing to him. Sometimes Michelle would get frustrated with us, as we were just hearing people who have our own issues, but she was extremely patient. I brought an assistant director onto the film who was also a deaf filmmaker, Ann-Marie Jade Bryan. She had worked with Michelle on another short she had made a few years prior to Compensation. Having [Ann-Marie] on set was a huge help in making sure we made these connections between deaf and hearing [crew] and that we were all making a collaborative project.

Filmmaker: In setting the film in Chicago, you were placing the story in a city you were very familiar with, albeit partly at a time that you never knew. I wanted to ask about the choice to build or expand the world through the implementation of archival photographs. Was it your discovery of the photographs that came first, or did you shoot your narrative scenes and then attempt to brainstorm ways to further contextualize the period?

Davis: After the script was written, we knew we eventually wanted to include archival photographs in the film, as Marc works as a public librarian and is also an archivist by trade. He helped me figure out and identify the archives I should try and visit, providing me with some keywords I could use to better specify my searches. You can’t walk into an archive and demand, “Give me all the Black photographs you have from 1905-1910.” You have to search by different subject matter. So, I would find the photographs in very unusual places. I could be looking for something in a file [titled] “people unloading bananas at the docks” or something about the “Visiting Nurses Association,” and I would’ve never known to look in those kind of places or categories if it weren’t for the archivists at the libraries I visited. These included the Chicago Historical Society, the Schomburg [Center for Research in Black Culture], the Howard University Library, the Library of Congress and the National Archives.

It took a long time to make the film. We shot Compensation in 1993 but didn’t complete it until 1999, because I was working as a professor at Northwestern University during the nine months that make up the school year. During the summers, I would continue to work on the film by making these archival research visits. Back then, we didn’t have the internet readily available, so I couldn’t remotely [search for photos] like we can now, but even if I made the film today, I’d still want to physically visit those archives. That one-on-one communication with the archivists, once they understand what your project is, is like developing a strong personal relationship, one that personally helped us build out the world of 1910s Chicago. As an independent filmmaker, I cannot make or [dress up] the streets of Chicago to look like 1910.

Filmmaker: think back to the 1906 photograph of the racially segregated school for the deaf and how we focus on one particular student, a Black woman who was presumably a real student attending that school, but then you transition us into the fictional narrative Compensation is telling, and it’s almost as if you’re using that young girl as a jumping off point [for the character of Malindy].

Davis: That photograph came from the archives of Gallaudet University in D.C., the leading American university for deaf and hard-of-hearing students. The photograph’s historical [context] that you read about in that scene’s intertitles was real. I am a narrative filmmaker, but I also like documentary and experimental film, so by using those [photographs], we’re including in our film the history of the Kendall School [the school’s original name, named after its founder Amos Kendall]. I was grateful that I could use those real photographs and include them in the fictional story we were telling.

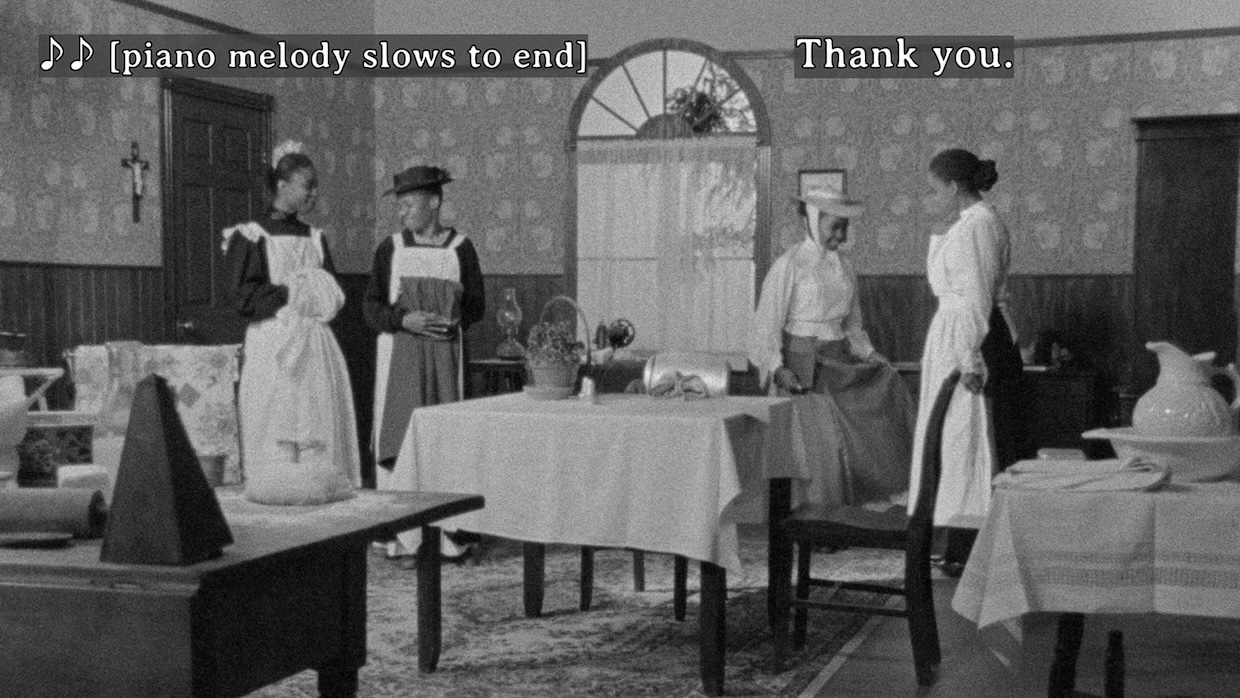

Filmmaker: You further play with the relationship between archival material and fictional narrative via recreation. There’s a sequence where the characters attend a five-cent picture show of William D. Foster’s The Railroad Porter, and you recreate it in your film. While it slightly takes on the feel of an “old-timey” silent film projected at more than 24-frames-per-second, I know you incorporated a twist on the material.

Davis: That’s one of my favorite parts of the film. We worked really hard with Reginald Robinson, our composer for that sequence, and he even plays the porter in that scene. We had so much fun! We shot at the house of two well-known Chicago activists, Lisa Brock and Otis Cunningham, filming the sequence in their backyard [laughs]. I wanted to use the real William D. Foster film [from 1913] but, as far as we know, it doesn’t exist anymore. It might be stored in somebody’s closet or maybe it’s sunken deep down to the bottom of the sea—these old films wind up in the weirdest places.

I found a synopsis of William Foster’s film in the Chicago Defender, so I adapted it and put a little “Zeinabu twist on it” so that it had a woman possessing a gun, as well as the guy. That was my little creative addition to the synopsis I had read in the paper. William Foster’s original version, made in Chicago between 1911-1913, was one of the very first Black films ever produced in the United States, so it was important to me that we honor that history and include as much of its original [essence] as possible. The Foster Photoplay Company [an exclusively African-American film production company founded in 1910] really existed and I wanted to adapt their work a little bit. Reginald had a wonderful time composing the score for that sequence. His music in those moments is very different from the ragtime sound and African percussion [by Atiba Y. Jali] used in the other parts of the film, as Reginald was trying to imitate a classic nickelodeon feel.

Filmmaker: Whenever you set an interior scene on a soundstage, I found myself curiously looking at the period details apparent in your set dressing, wondering how much you chose to include within the frame versus how much [to leave out].

Davis: I was blessed there. I had another experimental filmmaker friend from Milwaukee, Cathy Cook, serve as my production designer on the film and she researched all of those old wallpapers you see in [those interiors] and things from that earlier period so that we could incorporate them into Malindy’s home. Janina Edwards was the film’s art director and created all of the furniture pieces, making sure they were as authentic as we could possibly get them to the period. It really was all one set dressed in the same wallpaper. I had access to a soundstage at Northwestern University [where Davis was a faculty member at the time], so one week was spent turning the soundstage into Malindy’s home and then we redressed the set, turning it into Malaika’s home for the contemporary period. We have posters and contemporary photos or calendars placed atop them in the contemporary section, and a cross and photos of Black historical figures on the walls in the period section.

Filmmaker: It’s now been almost 30 years since you completed production on the film and just over 25 since you began publicly screening it. Just a few days before the film’s premiere in Toronto, your father passed away, and now, as your film takes on a new life and is reintroduced to the world thanks to this new restoration, your cinematographer has also passed on. So much of your own life has taken place concurrently with the film’s making, distribution and now restoration.

Davis: I was lucky enough to also have my dad be in the film, in the section where Christopher Smith is performing as Bill Young. That’s his big head in the back [laughs]. My brother, Kevin L. Davis, is also in the film as the character Tyrone. Kevin always used to tease me because it’s like, “Whenever you need to be bailed out because you don’t have enough money, who do you come to?” And it’s true [laughs]. He was the one with the engineering degree, not the film degree, so he made way more money than I ever did. He bailed me out when I needed help sometimes, so I was like “OK, I’ll put you in the film and you can [essentially] play yourself,” and he really did.

We were able to get Pierre to record his audio in August of 2023 as part of a group commentary track with Marc and I for the upcoming Criterion release. Pierre passed away in December of that year and I’m grateful that I was able to give him that chance to participate. He knew that the restoration was eventually going to take place, and believe me, I heard his voice when we were supervising the color correction. As another filmmaker from the L.A. Rebellion, the late Jamaa Fanaka, would say, “Filmmaking is secular immortality.” I love that. That’s exactly what it is. I really have a hard time sometimes because I miss my father and I miss Pierre, but I have this film, and they’re still alive because of it. The film will be released on Blu-ray by the Criterion Collection in August. We’re ready, finally, after 31 years, to give it [a proper release]. My brother keeps saying, “31 years, it took 31 years!” [laughs]