Back to selection

Back to selection

The Microbudget Conversation

We're Only Talking a Few Thousand Dollars by John Yost

The Microbudget Conversation: Blake Eckard Has Questions Without Answers

This week we hear from the Micro-Budget Filmmaker Blake Eckard. After I had put my first feature up on the web for free downloading, Blake contacted me and we began a three-year conversation on the highs and lows of micro-budget filmmaking. I think Blake’s take on the subject is one of importance and it needs to be shared.

“Orson Welles, by his own admission, didn’t believe in artists so much as “works.” He also hated (or liked people to believe he hated) talking about himself and his films. Although it may be fashionable to say it, I don’t think there’s any damn way in hell filmmakers are, or ever have been making films solely for themselves. That is to say, going through the entire process only to watch a completed work, a year or more later, on a computer monitor. We all want people to see our films, but I’m confounded by all the self-revealing speak.

“Orson Welles, by his own admission, didn’t believe in artists so much as “works.” He also hated (or liked people to believe he hated) talking about himself and his films. Although it may be fashionable to say it, I don’t think there’s any damn way in hell filmmakers are, or ever have been making films solely for themselves. That is to say, going through the entire process only to watch a completed work, a year or more later, on a computer monitor. We all want people to see our films, but I’m confounded by all the self-revealing speak.

I never read filmmaker blogs, but am constantly told I need to start one. “Nobody knows who you are, Blake!” a friend recently reminded me. “How is anyone going to know your films exist?” Of course they’re right, but I feel a sincere resistance to talking about my own efforts with any kind of point-of-view that could be deemed of a self-interested nature. It just feels arrogant (although I suppose every filmmaker could be labeled arrogant for assuming their works are needed in a world full of bad works).

I made my first “movie” on my seventh birthday. It was called Alien and was eight VHS minutes of second-graders running through the house, screaming and knocking shit over, as the Alien (my mom, cloaked in Great Grandma Ethel’s homemade quilt, and sporting a green ogre mask) chased down and killed us. Dad filmed. I showed this stupid-ass thing to everyone I could for years. Thought it was really something. Between seven and 17, I easily made over 100 little movies ranging in length from a few minutes to 45. I’d be humiliated to watch any of them today, even alone and drunk.

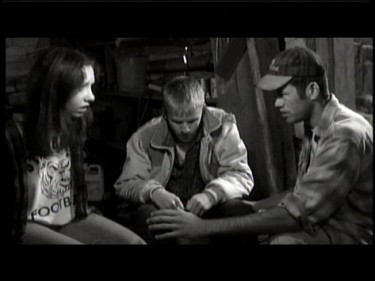

At 18, (as a senior in high school who wondered if he’d be graduating — I ultimately did with a class rank of 37 out of 37), I shot my first feature over the course of two weekends. Aptly named A Simple Midwest Story, (2001) (pictured above) it took three years to drag through post and was subsequently rejected by over 100 film festivals. Still, I again held a vivid sense of having created something worthwhile. Today I cringe at the thought of it, even though it’s quite highly liked by a tiny few (emphasis on tiny) and has screened in L.A., New York, Toronto; more venues than my next two features combined: Backroad Blues, (2006), and Sinner Come Home, (2007). I’m now nearly finished with a new film, Bubba Moon Face, and while first desires surround a scenario where the picture finds friends out in the world, I also hope I won’t have a hard time watching it in the future. Flaws and shortcomings aside, all my films mark who I was at the time of their making; showing my fascinations, frustrations (growing all the time) and beliefs.

I was probably around 12 when I discovered George A. Romero, Tobe Hooper and John Carpenter. Even then, I felt there was a deeper substance of meaning in the Romero pictures; Hooper wowed me with his raw, visceral aesthetics — still does; and Carpenter’s cinema always guaranteed a slick freshness, no matter what the genre. There was no Internet available, I’d never heard of IMDb, and blogs didn’t exist. The best way to find anything out about these directors was to pour through back issues of Fangoria magazine, which I did (not the easiest publication to find in rural Missouri). These guys, and later Stanley Kubrick, Robert Bresson, Jon Jost, David Lynch and Werner Herzog, seemed almost non-human to me. I wasn’t a fan-boy, thank God, but I was completely interested in these filmmakers, I think, because I assumed the work reflected who they were, and their works weren’t standard. It wasn’t about what was in fashion, it was about what was off-beat and mysterious — hard to find, too. I distinctly remember the great satisfaction I felt when, after years of hunting, I finally saw Jon Jost’s obscure, and very spooky road movie, Last Chants For A Slow Dance. It was made for zilch, looked it, but was one of the most incredible movie-watching experiences I’d ever had. I felt like it belonged to me. Certainly nobody I knew had ever managed to find it.

I still love movies and watch about three a week. Sadly, I feel no mystique in 90 percent of current films and audiences seem to be discussing cinema less and less in general. Filmmakers have been left to take up these reigns. What bugs me, then, is the lack of any talk (usually) in terms of the actual ideas or themes behind a film. Most topics revolve around boring-ass tales of how the shoot came together with no crew (welcome to the club), self-distribution prophecies (guess work at best), and the joys of being liberated by improvisation (barf).

I think it’s great that no Terrence Malick interviews are on YouTube, and (detouring into literature) that Cormac McCarthy’s one taped interview remains a guarded talk with a seemingly perplexed Oprah. When people complain that the Duplass Bros. don’t have a Facebook page, or Ronald Bronstein isn’t tweeting about his new film, I’m digging it. Frownland, to me, is one of the few indies in recent memory that feels like it belongs to another time, and I love the fact that it totally pissed off and bewildered so many. Where did it come from? What’s the point? Why does it look like it was filmed 20 years ago? You’re provoked to talk about the film itself. The film and it’s mysteries. David Lynch has been asked a thousand times how he created the baby in Eraserhead. He’s still never revealed this secret, nor explained what the film means. It infuriates many. Not me. The not knowing is precisely part of the attraction, part of the experience.

Questions make movies live, not answers. Never the answers.

Something a bit weird happened two weeks ago. A friend returned copies of my films that he’d borrowed four years ago. Feeling a bit whimsical, I popped in Backroad Blues, mainly to see if it’d still play (it locked up with 5 minutes left…my only copy). It’d been years since I’d watched it through and while I was mildly mortified with my camerawork, twice in 85 minutes I was unable to remember what happened next, and in one instance found myself watching a scene I had no memory of shooting. I suppose it was as close to seeing the film from an audience standpoint as I’ll ever get. The film felt old, like I hadn’t even made it. An off-beat, 16mm, Missouri-shot parable with no past, no names, and no fame. Nothing but a poorly-attended IMDb page with an absurdly high star rating. I’m not pretending it’s great cinema, but it felt sort of wonderful in a way.

We own our films until they’re done. It’s up to the world to hold interest in our labors, and that’s sorta that. Some level of self-promotion is a must, sure, but who wants to let out all the secrets? Fact is, none of us know what we’re doing and most movies, indie or otherwise, offer nothing in the way of lasting art. True art comes from naive sincerity, blind effort and dumb luck. It isn’t about supplying answers; it’s allowing wonderment to breathe. — Blake Eckard

I want to thank Blake for contributing…even if at times he felt he shouldn’t. The subject of how much are we suppose to give away in a time that EVERYONE is pimping the shit out of their work down every avenue, is an important one. I agree with Blake…even though I’m putting this blog together and filling it with links….it’s not lost on me. I think that a healthy mix of both might be the way to go, but it will be the folks who focus on the work, and who focus on getting better with each film that will eventually lead the way in this niche, if not, industry. I also feel that it’s our job to do what feels right and create a market without so much excess need of behind-the-scenes and talk about how things were shot. I made the mistake of making a ton of extra behind-the-scenes with my last film. It completely stripped the film of any mystique; The audience had everything it needed and the film was dismissed. Where is the line? I encourage you to ask that question and keep the conversation going.

Cheers

John

We’d never turn down the chance to hear from you, especially micro-budget fans and filmmakers. To become part of the conversation please send us your thoughts, responses, and questions.