Back to selection

Back to selection

The Microbudget Conversation

We're Only Talking a Few Thousand Dollars by John Yost

The Microbudget Conversation : Films Too Small To Fail

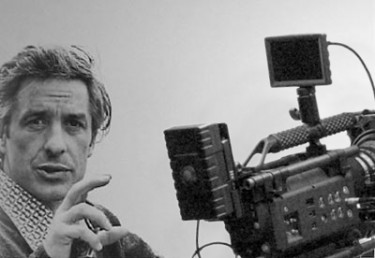

I first met Zak Mulligan through my DP Sean Donnelly a few years back. After a bit of back and forth on the merits of Kickstarter, I helped him with a little production design on his first feature, and we became fast friends and supporters of each others work. Zak and his directing partner Rodrigo Lopresti were recent participants of IFP’s Independent Filmmaker Labs with their first feature film I’m not me. Zak also won the Best Cinematography award at Sundance last year for his work on the film Obselidia. He’s here to talk a bit about the advantages of staying small.

Picture this: Two guys with a camera, a rental car, and an afternoon to kill. The duo take a drive out of New York City with no particular destination in mind, possessing only the vaguest of ideas and a desire to shoot something… Anything. Suddenly a kernel of a thought takes hold and the first frame is captured. What now? One idea flows into another until they have something. It’s not exactly a short film; it’s more like a doodle. A quick sketch that could perhaps be developed later on. This humble beginning marks the inception of my latest film “i’m not me” (pictured right).

Along with actor extraordinaire and my directing partner Rodrigo Lopresti, we continued creating these doodles for several months. It was great fun, required no pre planing, and most importantly nothing was sacred or precious. Our creativity spawned out of whatever we had in front of us at that moment. These moments then led to new ideas and we began to branch out by enlisting the help of other actors we knew. Before we could even finish editing all the pieces, we realized we had something much bigger. So, we decided to put the camera away, break out the laptop, and start writing a script.

The following weeks after finishing the script, we thought long and hard about how to get this thing in the can. A few strategies came to mind. The first we tried was to ‘get a name attached’, watch the investors line up with fists full of cash, and count the money as it siphoned into our bank accounts. While we did have some early success in getting the project in front of people, we quickly realized that it was going to take a while. An incredibly tedious and very long while, in fact. We couldn’t help but wonder, how had we got here? This wasn’t filmmaking! We’re not producers, at least we didn’t want to be. There had to be an easier way. Well, it turns out there is. This is the big secret. This is how we made our film. Drum roll please…. (Ok, it’s not really a big secret or even that dramatic!) It’s very simple. We decided we would go and make “i’m not me” with the resources we had available to us. That’s about it.

The wonders of the information age were all around us, so we decided to take advantage. The internet was our first stop. We launched one of the very first Kickstarter campaigns, found a couple private financiers, and filled in the rest of the gaps with our own money. The whole fund raising process came together in a matter of weeks instead of months or years.

We then proceeded to shoot the film piecemeal over the next year. We borrowed a friend’s house upstate for a couple weeks as a location, shot city locations when we had free time, and begged others for their cars/apartments/gear/help/whatever. I now owe enough favors to keep me busy for next decade or so. Most of the time the only people on set were the actors in front of the lens and me operating the camera — no PA’s, no assistants, nobody.

What’s truly remarkable about our story isn’t the process of making this film or how much money we did or didn’t have, it’s the fact that we were able to make this film at all.

Cynicism within independent cinema is pervasive. Filmmakers lament the rise of the digital, the diminished use of film, and the lack of a clear means of financing, distributing and exhibiting these films. I’ve also heard more than a few complaints about the sheer number of films being created now. Sundance submission numbers broke records this year. It’s enough to make anyone throw their hands up in despair and avoid the process all together. However, this way of thinking is all wrong. Right now we are in the middle of a historic sea change. It is now cheaper than it has ever been in film history to create films with high production values. While this may be a very grand sweeping statement, it happens to be true. Just imagine if John Cassavetes had a RED camera and a laptop. It’s uncertain how much more work he would’ve produced, but I bet you the entire “i’m not me” budget he would have created more films. I have to admit, I’m not always a fan of the HDSLR fad, but one cannot deny that these little cameras (when in the hands of a skilled artist — but that’s another article) can create very nice images at a very low price point. Combine this with a good script and some talented people, and you may just have a crack at an Oscar, or at least some awards at a major festival.

When I started making films (not all that long ago) we had to scrimp to buy 16mm film and borrow whatever camera we could find. If we didn’t have that kind of money we were stuck shooting 60i standard definition video on a tiny little 1/3 or 2/3 inch chip camera. Needless to say that didn’t look very good at all! We didn’t have the luxury of exploring, practicing, or making doodles in a format that was of a quality to be taken seriously as a story telling medium. Democracy has truly arrived in filmmaking, and the side effect is volume. Volume of productions does not necessarily translate to better quality films, and it is true that there is now a large base level of noise, but undoubtedly good projects will rise above the noise and be noticed by those who care to look. At least I hope so. The noise at Sundance last year was as loud as ever. You heard the buzz before you could even hit the slopes and ask “Was that Mark Ruffalo on a snowboard?” Many of the media frenzied, buzz worthy titles eventually gave way to the projects benefiting from a repeating wave of good word of mouth. At the risk of sounding cynical, rarely did the buzzed about films benefit from good word of mouth.

Democracy is coming. This shift has displaced traditional power structures giving much more of it to the artists. It’s really exciting to think about micro budget filmmaking as a means of liberating the artist from the machinations of the marketplace. This is what I call “too small to fail.” When there are no investors to be indebted to, one has the freedom to take risks and experiment. This is very much in keeping with the spirit of “i’m not me” It is a film without any big stars (yet!), an unconventional script (we had a tech script so much of the dialogue was improvised) and a very unusual production model. These are all things that wouldn’t have been possible had a studio been involved, or if large volumes of cash had been coming our way.

What does it mean to be financially emancipated? It means you are too small to fail. These kind of films are not motivated by box office numbers, which of course makes for a different kind of film. If this kind of film loses money there’s nobody there to care very much. However, financial gains from a few films (Paranormal Activity, The Blair Witch Project) should not become the main motivation for creating more of these kinds of films. This type of film is more a place to test new ideas, take risks and hone your craft. It’s a means to make a doodle. It’s a realm where just making the film is success enough. I love doodling.

But is this democracy a good thing? Were the old barriers to entry a positive situation allowing only serious filmmakers to produce work? Has a paradigm shift really happened and if so what does it mean for the future of this medium? Move beyond the noise and find out for yourself. – Zak Mulligan

Zak Mulligan is a cinematographer and most recently a writer and director who splits his time between New York and Los Angeles. Last year he took home the Excellence in Cinematography award from Sundance for his work on the narrative competition film Obselidia. me@zakmulligan.com – www.zakmulligan.com

I think Zak brings up some very important points that are on the forefront of discussion in this industry. Do micro-budget films belong in the arena with the big boys? Is indie too often used as a marketing ploy? Is there room for micro-budget in the indie world as serious films? Is the micro-budget model financially feasable? Or is it just for hobbyists, up and comers, or weekend warriors? Is the market flooded with too many test films? Is it great to be too small too fail, or would it be better to doodle in your own time and make each big budget venture a home run? Questions I put to you. Cheers, John

We’d never turn down the chance to hear from you, especially micro-budget fans and filmmakers. To become part of the conversation please send us your thoughts, responses, and questions.