Back to selection

Back to selection

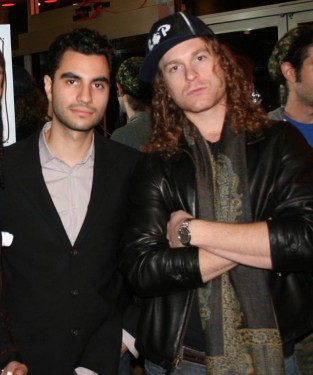

Adam Bhala Lough And Ethan Higbee, Tha Upsetter

Widely revered in reggae and hip-hop circles, Lee “Scratch” Perry is one of 20th century music’s most influential and mysterious artists, a tried-and-true rasta man whose lasting contribution goes beyond spawning some of reggae’s most seminal acts. He was, in fact, the driver for the aesthetic innovations that germinated into the two genres mentioned above, and he reinvented the image of the studio engineer from mere technician to artistic focal point. Now in his mid seventies and expatriated to Switzerland, he’s the subject of the feature-length doc The Upsetter, from the directors Adam Bhala Lough (The Carter, Weapons) and Ethan Higbee (Red Apples Falling). NYU classmates, frequent collaborators (Higbee has scored several of Lough’s previous features) and nearly lifelong reggae fans, Lough and Higbee received unprecedented access to the beguiling Perry, who speaks in gorgeous, puzzle-like sentences that require significant scrutiny to unpack.

The Upsetter screened at over a dozen stops on the fest circuit, including Edinburgh and Karlovy Vary, and just now is finding its way to theaters, nearly two years after its festival run ended. Like several of Lough’s previous films, it evolved significantly after playing at festivals. In the interim some footage has been lost, a few vintage photos of Perry, Bob Marley and other key figures in the early days of reggae have been unearthed and its new, slightly slimmer cut features voice-over narration by Benicio Del Toro . The Upsetter opens in Los Angeles at the Downtown Independent this Friday. It screens at the Maysles Cinema in Harlem April 3rd.

Filmmaker: How did your interest in Lee Perry evolve into the desire to make a film about him?

Lough: I’ve been interested in reggae since I was a little kid. My dad used to play Bob Marley since I was very young. I wasn’t really aware who Lee was though.

Higbee: I’ve been obsessed with him since high school really.

Lough: Probably in middle school I saw a solo record of his at Tower Records or something. He was very prominent and interesting and weird. Listening to it, it was so bizarre, it wasn’t like anything I had ever heard. So the seed was always planted there for me from like twelve or thirteen years old. I met up with Ethan at NYU and he was already talking about it back then.

Higbee: I’ve wanted to do this film for at least ten years. I talked about doing this doc on Lee “Scratch” Perry the entire four years we were there at NYU. As far back as freshman year I was actively pursuing it, trying to contact Lee through whatever channels I had at the time, which were admittedly not much, although I would see him at his shows sometimes. After school, Adam and I remained close, we worked on a lot of projects together.

Lough: A few years later, after I had made Bomb the System, it got picked up for release in Japan and our distributor there did a wide release of the film, way bigger than the one it got here. It was about 13 cities or so. The distributor flew Mark Webber and I out to do a press junket. It was a lot of press, answering questions for 12 hours a day for a week straight. I was at the office of the distributor and I saw a stack of DVDs laying on this guy’s desk and they were all reggae DVDs, every single one of them. I thought it was kind of strange so I asked one of the guys there, “What’s going on, what’s up with these reggae DVDs?” And he said, “Well, reggae is huge in Japan and we’re looking for reggae movies. Do you have any ideas, are you working on anything?” I remembered Ethan talking about this documentary for four or five years and I immediately pitched it to the president of the company and he agreed to distribute it in Japan.

Higbee: He called me up from Japan and was like, “Yo, do you want to do this?” and I was like, “Let’s do it, let’s do it now!”

Lough: That put some fire under our asses to get it going.

Higbee: Since then it’s just been Adam and I, we financed it, researched it, produced it and are distributing it here in the States ourselves. It’s been such a blessing to get to know Lee and his family. He has a special, strange, incredible energy about him. We met him at a point in his life when he was really ready to open up. It’s just been a huge gift.

Lough: As soon as I got back to New York, Ethan and I really started grinding on it.

Filmmaker: Was it difficult to get him to do the film?

Higbee: We were finally able to get to him and later that month I got on a plane and flew out to London to meet with Lee. That was something I’ll treasure for the rest of my life.

Lough: I went to start production on Weapons and he called me from London and was like, “I’m with Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and we’re going to do this!”

Higbee: He was just so generous. I had just sat down to dinner with him and he had taken a liking to me and agreed to do it right then and there. Once Adam got off of Weapons the first thing we did was spend eight days at his house. There was a lot of burning involved. Fire is very important to Lee. He creates things, and then burns them; he has no interest in preserving his work, or items that for most of us would be of lasting significance. We burned other things as well. [laughs]

Lough: Lee had been asked time and time again for 20 or 30 years by random white people with video cameras who are like, “Hey man, can I do a movie on you?” [laughs] Time and time again these people didn’t follow through. We met some of them along the way. They just all don’t have any follow through. We had the follow through, so when we showed up at his place in Switzerland an hour-and-a-half outside of Zurich in this random ski town, he knew it was on, these guys are for real. From that day forward he was invested in it. As we continued shooting, he started to trust us and really like us. He became like a grandfather figure to Ethan and I.

Filmmaker: How did you get access to all of the amazing archival footage of him and the images from the early days? I can’t imagine there was very much stuff out there.

Higbee: It would have made our lives a million times easier if we had been able to afford a researcher. It was just the two of us finding stuff where ever we could. For the original cut of the film, we pulled a lot of stuff off of the Internet. I would do a new search for Lee Perry videos on Google every week. This process went on forever. Don Letts really helped up out a lot.

Lough: We did it the old fashioned way. We would go to people we knew were a fixture in the culture, like Don. We went to Don Letts and asked him if he had any footage and he was super cool about it. He broke us off with some amazing archival footage. Then we’d ask him, “Well, who else do we go to?” and he’d direct us to someone else who could help. See, Don is a huge part of the reggae culture in London. He’s the reason reggae blew up in London. He was a DJ back in the ’70s. He literally brought reggae to the punks. He was hanging out with Johnny Rotten, he was friends with The Clash and he was right there at the beginning of punk music. He’s British, but his parents were from Jamaica. He started playing reggae and got all those guys into it. He’s also a really great documentary filmmaker in his own right. He owns almost all of the great punk footage of the Sex Pistols and The Clash that you see played time and time again on TV. That’s all his stuff. He also directed a great documentary called Punk Attitude. He’s made a few other features too. If you’re ever going to do an interview with someone on reggae or punk, he’s the first guy you call. I was introduced to him by Jim Jarmusch, who was the first person I called when we started this thing, I said “Jim, I need to get in touch with Paul Simonon from The Clash, can you hook me up with him?” He hooked us up with a ton of dudes — Jim knew all those dudes. So that’s how we were able to find so much of that footage — through Don Letts. We put a special thank you to him at the end of the film; he was very helpful. It all sort of spitballed. We just amassed all this amazing footage going door-to-door basically.

Higbee: We have about all of the old footage of Lee Perry that anyone ever took. I doubt there’s much of anything we didn’t find. I would be in someone’s house dubbing a VHS tape while Adam would be talking to them and interviewing them and stuff. Then we headed back to California and edited the film in my home in Los Feliz, in my room, and that’s where we would just find extra stuff on the Internet, a lot of which was difficult if not impossible to clear. That’s been a long process of just going back and clearing all of the footage we culled together from all these disparate sources.

Filmmaker: How has the cut evolved while the film has been on the fest circuit? When I initially saw it at BAM’s AfroPunk! Film Festival in 2008, it didn’t include any narration by Benicio Del Toro.

Lough: You’re right, there have been three versions of the film. The first one was really a rough cut, it had a very different ending and a whole 20 minutes about his family. It was really great stuff, poignant stuff and some of it was quite sad. Ultimately we ended up taking that out because it was slowing the film down but also because we wanted to focus on his music. We were trying to have our cake and eat it too. A lot of the focus of the second half was on his family and the spiritual aspect of his life, him discussing God, ganja, music and pussy, you know. [laughs] So we choose to cut out the family section and that changed the thing drastically and then Ethan reached out to Benicio’s people.

Higbee: In the original cut I did the voice over. That was never our idea for it to be me when it was finished, but it was there temporarily. It took me about a year to get to Benicio. I dealt with a guy for a long time who claimed he was Benicio’s voiceover agent, which turned out not to be true! L.A. is full of people like that, who say they represent people and they probably don’t even know them. Finally I was able to reach his agent’s assistant, who, knowing he was a fan of Lee’s, introduced us and the project. Eventually it got to him and he agreed to do it.

Lough: Benicio came in, we worked with him for with him for a couple of days, and then he came in again and did a second session of voiceover recording. He really wanted to do it right. He rewrote lot of stuff and made it stronger, more concise. He was amazing, he did a phenomenal job. We had to recut things to fit his voice over a bit, but it only made the film better.