Back to selection

Back to selection

The Microbudget Conversation

We're Only Talking a Few Thousand Dollars by John Yost

The Microbudget Conversation: A Filmmaking Tool

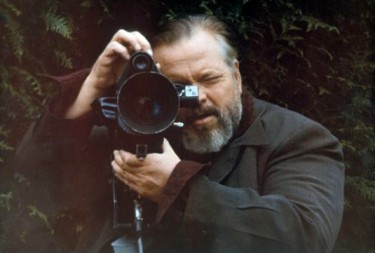

After our last post the response was overwhelming in regards to what micro is, if it’s important, and where it’s headed. In the spirit of conversation I worked with Todd Looby (pictured below) on a post almost exactly the opposite of Scott’s. Todd sees micro-budget filmmaking as a skill, a tool, and somewhat of a stepping-stone. Our conversation wouldn’t be a conversation without this point of view.

To me, microfilmmaking is not an end that anyone in his or her right mind should be pursuing. Of course, as people interested in filmmaking, we are not necessarily right in the mind. There are those — many of whom read or write for this column — who live and die by a microfilmmaking manifesto. They hope that somehow, through their work, audiences will “see the light” and figure out that all is lost in Hollywood and at festivals, and that we must return to our roots by watching a shaky film about a character wrapped up in an über-personal struggle. And, once audiences come around, a viable market will develop for that work. Even if that happens, the sheer volume of microfilms in existence ensures the fact that any revenue will be spread thin and you’ll still struggle to get seen.

Don’t get me wrong, people have had continued success as microfilmmakers, and I applaud their efforts and success. However, what you will find is that these people, conscious or not, were attached to some genre or movement which served as an automatic marketing device. Like it or not, effective marketing — ie. Hype — is the only means by which they may eventually make a living doing what they love. In any industry, marketing also plays a role in the degree of revenue earned, but in film, it is the only means by which revenue is earned. Since film/art has no material value, it is bought solely on the value attributed it by others who deem it trustworthy — friends, critics, fest programmers. There is no inherent “usefulness” in art that demands an exchange of currency, despite how moving or enlightening it may be. Needless to say, if you make a good film, it will get seen, but if you can’t market the film, and you’ve tapped-out your family/friend funding sources, you’re more or less done, regardless of how low you can budget.

To be honest, publicity is a huge reason I’m even writing this. Most people who read this will have never heard my name, but now they will — and thus may be potentially interested in my films. That’s my story; perhaps for you it’s different. Some of you may continue to make films that don’t earn revenue because you are on a trust fund, you are supported by your government, you have a lot of gullible, rich friends, you are independently wealthy, or you wish to devote 100% of your free-time from your day job to making films. At this point in my life, as my wife and I start a family, I fit into absolutely none of these categories. I aspire to make a viable living from filmmaking and am not married to the idea of microfilmmaking as some sort of ideal — nor was I ever. And, besides it is completely exhausting — at least the way I work.

Now, let me make sure I’m clear in my views that I respect microfilmmakers more than any other filmmaker, simply because it’s more difficult. I also tend to like the first films by many directors more than their subsequent studio efforts, simply because you see the inventiveness and the brilliant ways they worked around constraints, pushing the boundaries of the medium and brilliantly transforming the subtle and ordinary to the profound. People can talk all day about Jim Cameron’s “pushing the medium” and I couldn’t give two shits. Whatever he does visually is not going to connect me to a character in a new way. And every time I hear a big Hollywood director bitch about the constraints put on them by the studio I have to laugh because it is mostly their own fault. They put themselves in a position to have their vision compromised. People seek the studio system for security, for the big toys, access to “stars,” for the red carpet, etc., and then they bitch when it compromises their art. What did they expect — a blank check? Now, once again, there have been a few that have made this transition successfully and I applaud their success. Others simply found out the grass wasn’t greener. Will I be one of them? Probably not, for two reasons: one, I won’t make it that high, and two, if I did, I would be honest about why I sought the backing of a studio.

One of the saddest stories I ever heard was at the inaugural Iowa Independent Film Festival in 2007. The fest is the brainchild of Indie-icon Henry Jaglom. Henry was one of Orson Welles’ few and closest friends toward the end of his life. Henry announced the “Orson Welles Award” given to the filmmaker who most inventively employed the medium. While introducing the award, Henry told the story about how Welles simply could not get another film funded after F is for Fake, and he died sad and frustrated. was at the fest premiering my micro-budget first feature, The Site. So, I was completely dumfounded by the fact that the medium’s arguably most respected director could not get a film made.

Now, to be fair, Welles could have been considered a microfilmmaker in his day. In reading his bio, he always tried to defy convention and work around the budget constraints that were heaped upon him as his reputation became less trustworthy. However, I think his problem was that although he had the heart and desire to be a low budget filmmaker, he simply never learned how to do it. And truly, the only way to know how to do it is to go through the process from start to finish. To have non-actors in roles, to figure out a schedule that meets logistical constraints, to work without a crew, to have no locations — in short, to have your hand in every possible detail that leads to sculpting an engaging character or an engaging story. Since the director must always see the big picture in the tiniest of details so should he or she, at one point, be responsible for conceiving of the ideas behind each and every aspect.

Directors like Steven Soderbergh and Richard Linklater, who had come up during the previous indie revolution, will never run into the same problem as Welles. And they seem to continue to exercise that microfilmmaking muscle so that they will have the skills to survive while budgets continue to shrink. This is the fact that filmmakers on all levels — except those at the top tier — have to face. Dramas, personal stories, melodramas, low-key comedies, romantic comedies, will all have budgets slashed drastically in the coming years as revenue from these types of films becomes more scarce. So, microfilmmakers are at an advantage because we will all know how to get around any and every constraint. Some filmmakers, regardless of how successful, simply do not know how to do that. Others will sit on great scripts until the budget they imagined becomes available. Sure, suffer for your art, but do it during the producing and marketing period, not in pre-pre-pre-production.

For me, microfilmmaking is a tool like any other in the process of filmmaking: it is a means to an end. And it is a means I will continue to employ as long as I am able, or until people think it wise to pay me money to make films. Through microfilmmaking I have developed a small, but engaged audience, I found my voice, and I may have even attracted investors to my next projects. Finally, if I am able to reach the level to make films for a living — regardless of how meager — I will always know of a way to do it cheaper than the other guy without sacrificing the content. For each of these reasons, it is an invaluable exercise and incredibly exhilarating. But do not expect microfilmmaking itself to ever be a sustainable way of making a living. And do not think that filmmaking of any other kind is impure. Be honest with yourself and remember the bigger budget, if not Hollywood films, that made you want to be a filmmaker. — Todd Looby

–Todd Looby is is a mostly self-taught, award-winning filmmaker based in Chicago. The Site (2007), Todd’s first narrative feature, premiered at Henry Jaglom’s Iowa Independent Film Festival and screened as part of IFP’s “Meet the Filmmaker” Series. LEFTY (2009), Todd’s second narrative feature, was named one of the “Top 10 Movies of 2009…” by the Chicago Tribune’s metromix and is currently being distributed by IndieFlix, Inc. Currently, Todd is adapting the non-fiction book, A Saint on Death Row — written by New York Times Bestselling author, Thomas Cahill — into a narrative feature film. Finally, Todd is set to shoot a new microfilm, Be Good, in late June, 2011. Be Good will star Amy Seimetz (Off Hours) and Thomas Madden (LEFTY). Looby and Joe Swamberg (Uncle Kent) will also appear. Mike Gibbiser (Finally Lilly and Dan) will shoot and Frank V. Ross (Audrey the Trainwreck) will record sound.

I am one of those folks Todd speaks about early on in his article — I live and die to make films, and I also see micro-budget as a final destination instead of a stepping-stone. My goal is to make micro a fiscally viable endeavor. BUT, this is a place where all ideas are welcome and all voices pondered. I love Todd’s honesty and I really dig what he’s saying about taking those lessons learned in micro to the big boys. If we could learn to be less wasteful, more resourceful, and rely on good writing and acting to tell our stories, we may have a chance at reforming this industry, or at least steering it in a better direction. Every day more and more people pick up a camera for the first time and the people who are used to large budgets are pushing themselves into territories that challenge their abilities. Whatever your motivation is, please keep challenging yourself, our industry, and your viewers.

braveandthekind@gmail.com

Todd Looby photo by Maya Adrabi (mayashoots.com)