Back to selection

Back to selection

THE 2011 MONTREAL WORLD FILM FESTIVAL

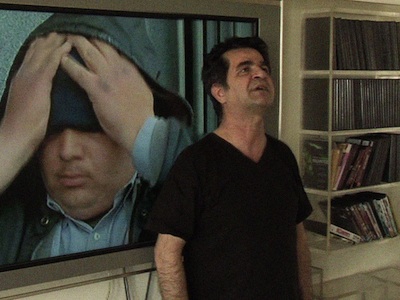

"This is Not a Film"

"This is Not a Film"

C’est dommage. Despite the fact that the summertime Montreal World Film Festival is 35 years old, it continues to be eclipsed by its (year) older, bigger and bolder Anglo relative’s annual gala in September. Nevertheless — and even if Catherine Deneuve hadn’t been honored with MWFF’s lifetime achievement award — the fest has much to buzz about. For one thing it’s headquartered at the Quartier des spectacles, right in the entertainment heart of a gorgeous Paris of the North (America) that made this bi-continental critic miss Europe a little bit less. Secondly, this UNESCO-appointed City of Design has a vibrant cinephile culture, evidenced by both the Cinématheque Québécoise, which maintains an international collection of 35,000 films from all eras and hosts free exhibitions, and the National Film Board’s (also free to the public) sci-fi-like CineRobotheque, which makes 10,000 movies available on its 21 touch-screen-accessed “personal viewing stations.” Thirdly, both of these institutions are located mere minutes away from the Cinéma Quartier Latin and the Cinéma ONF (also housed in the NFB building on colorful St. Denis), two cozy venues that screened a handful of selections that, like the host city itself, transported me completely to another world.

Since the Iranian director Jafar Panahi served as president of the MWFF jury back in 2009, when he was still allowed to leave his homeland, it makes sense that his latest, uh, effort This Is Not A Film (pictured above) would be selected to screen out of competition this year. The celebrated filmmaker, who made international headlines last December when the Iranian authorities handed down a six-year prison sentence along with a 20-year ban on making movies (and penning scripts and giving interviews to the media), which he’s still appealing, is no Lars von Trier-style provocateur. Watching the work, created with co-conspirator Mojtaba Mirtahmasb, I was reminded of an interview I did with No One Knows About Persian Cats director Bahman Ghobadi and his co-writer Roxana Saberi, the Iranian-American journalist herself jailed in Tehran and accused of being a spy in 2009, eight months before Panahi was arrested. Ghobadi told me that when he finally decided to leave Iran Panahi urged him not to do it. Panahi thought it a mistake for him to leave Iran. “Now, in retrospect when I look back, I see that I really didn’t make a mistake,” Ghobadi said. “I’m actually happy that I left.”

And yet part of the reason Panahi and Mirtahmasb’s “film” is such a revelation (I actually exclaimed, “Wow!” after the last shot, something I haven’t done since seeing Kiarostami’s Certified Copy — these Iranians really know how to make that final image pack a punch) is because it’s risk-taking at its finest, and presents a different, more mature face of rebellion than those we have recently seen on the evening news. Panahi is a rooted family man still in love with his country — and at war not just with the establishment, but also with his own artistic nature, his very soul. For Panahi to be ordered not to make movies is a command as ridiculous and impossible to obey as being told not to breathe. At its simplest and most Kafka-complicated, This Is Not A Film is a day-in-the-life doc that ultimately proves you can take the film from the filmmaker but you can’’t take the filmmaker out of the film. Even as Panahi attempts to navigate around his restrictions — as if the court had only sentenced him to a real-life Five Obstructions, albeit with dire consequences — with the choice of title, and by only acting and reading his screenplay, which was rejected by the state and never made, he frets about over-saturation and asks the man filming him (Mirtahmasb was selected for the task since he’s working on a movie about Iranian directors who aren’t working) about numerous technical issues.

And we get caught up in Panahi’s fervor, his fictional tale about a girl who, ironically, is locked away in her house and becomes suicidal, parallels the director’s own perhaps self-destructive impulse in testing the limits of the ban. (In an apt metaphor Mirtahmasb even captures Panahi’s child’s pet iguana literally climbing the walls.) Add in the street noise from “Fireworks Wednesday” that sounds like gunshots, and editing that makes the average Tehran day seem wildly unpredictable, and This Is Not A Film becomes a nonfiction thriller in which mundane events could turn into life-changing ones at the drop of a hat. After showing us the actress and locations he’s chosen — images stored discreetly on his iPhone — Panahi practically teaches a course on filmmaking via his own movies seen on DVD, freezing scenes to explain when an actor is “directing and when a location is “directing.” Excitedly, Panahi realizes that a director must actually be in production in order for cinema’s magic to happen – to discover those happy accidents that are not written in any script. “It’s important that the cameras are ON,” Mirtahmasb says at one point. Just documenting — bearing witness — is half the battle. By the time the unfamiliar custodian Panahi decides to follow on his rounds enters the picture This Is Not A Film also becomes a testament to truth being stranger than fiction — one that culminates with a scene straight out of Hollywood hell right outside the filmmaker’s front door.

Another flick that stayed with me long after the credits rolled, though for a much different reason, was Chinese Take-Away (Un Cuento Chino), which screened in the Focus on World Cinema section. Unlike the Cannes-certified This Is Not A Film, I knew next to nothing about Argentine director Sebastián Borenszstein’s sweet and strange comedy (“based on a true story,” according to one subtitle) before seeing it. But since I have a terrible crush on its charismatic lead actor Ricardo Darin — Argentina’s answer to Vincent Cassel — I decided to check it out. Infused with Latin magical realism this odd bird of a feature follows an Argentinean loner named Roberto (Darin) who collects absurd tales he finds in the newspaper and then fantasizes himself into the tabloid events, Terry Gilliam-style. The film opens with a falling cow coming between lovers on a serene lake in China and gets progressively weirder once the now-heartbroken immigrant is thrown out of a taxi and into the curmudgeon’’s obsessive-compulsive life in Buenos Aires. An unlikely relationship forms when the non-Spanish-speaking sad sack becomes the proverbial albatross as Roberto is thwarted at every turn attempting to find the guy’’s uncle. Would the movie have stuck in my mind without the riveting presence of Darin? Probably not. C’est la cinéma.

But there was one particular film — a Documentaries of the World selection hailing from Canada, in fact — that needed no star power to keep me glued to the screen. Aaron Yeger’s nonfiction debut, A People Uncounted, was a one-of-a-kind find, not least of which because it introduced me to a virtually unknown piece of history buried beneath the weight of the biggest event of the 20th century. And it did so with artistry (the lack of which is probably my biggest pet peeve when it comes to most “issue” docs. In addition to sober talking heads and archival footage Yeger uses pop-culture examples of stereotypes, upbeat animation and an evocative score to tell the tale of the Roma (Gypsies), Europe’s largest minority group, an estimated 500,000 of which were wiped out by the Nazis (yet not one Roma was called to testify at Nuremberg). The Canadian filmmaker travels from Toronto to Slovakia, from Germany to Ukraine to Romania, to thoroughly investigate — often through the testimony of Holocaust survivors — the Roma’s’ circumstances and how their past shines light on the present. Historically, the Roma’s’ persecution parallels that of the Jews, minus the existence of post-WWII relief and restitution organizations. (One wonders why Charlie Chaplin — both active in the war effort and descended from British Roma — didn’t do more when it came to the Gypsies. Fortunately, Yeger’s film is a fascinating, hyperbole-free inquiry into what one recent study determined is the most discriminated-against group in all of Europe — a noble people focused, post-War, squarely on the difficult task of preserving their heritage and making their lives count.